Gig Economy Workers’ Livelihood: A Qualitative Study of Ride-Hailing Platforms in Bangalore City, India

June 2023 | Ananya Radhakrishnan and Namrata Singha Roy

I Introduction

A digital platform economy, popularly referred to as the ‘Gig Economy’, is one of the most notable developments in the 21st-century job market. In terms of definition, the gig economy is “the collection of markets that match providers to consumers on a gig (or job) basis in support of on-demand commerce. In the basic model, gig workers enter into formal agreements with on-demand companies to provide services to the company’s clients. Prospective clients request services through an Internet-based technological platform or smartphone application that allows them to search for providers or specific jobs. Providers (i.e., gig workers) engaged by the on-demand company provide the requested service and are compensated for the jobs” (Donovan, et. al. 2016). Thus, the gig economy is characterised by short-term contracts or freelance work instead of traditional‘permanent’ jobs. In lieu of a fixed wage, gig economy workers typically get paid for each ‘gig’ they undertake. The novel aspect of gig work is that the labor supply matches the labor demand through an ‘online platform’.

The Growth Story of the Gig Economy in India

The Digital Revolution in India caused by explosive internet penetration has made smartphones and cheap data affordable to millions (Radhakrishnan A. 2020). With a large working population and workforce growing by a whopping four million every year, the advent of a gig economy has impacted the Indian labor market to a large extent. Thus, digitization, internet penetration, a technologically skilled workforce, advancements in information technology, alongside a booming startup culture, propel India’s gig economy. Over the last few years, we have seen the exponential growth at which online service-providing apps such as Uber, Ola, Swiggy, or Zomato have taken over different sectors of the Indian market. These companies make up the largest employers of India’s gig economy, and hence India has now become one of the largest hubs worldwide for the gig economy (Radhakrishnan A. 2020).

According to a Mckinsey report, approximately 20-30 per cent of the total workforce in developed countries is engaged in some independent work (Manyika, et. al. 2016). Another study titled ‘Insights into the freelancers ecosystem’ conducted by PayPal with 500 Indian freelancers in 2017 state that 41% of Indian freelancers have witnessed significant growth with 80 per cent of them working with international as well as domestic clients. App-based technology has increasingly replaced intermediaries and directly allowed buyers and sellers to contract work. Platforms such as Upwork, Flexing It, and TeamLease are pioneers at the Indian forefront regarding gig work. According to the India TeamLease report (2019), in the 2018-2019 second half, approx. 1.3 million workers became part of the gig economy, which boosted growth by 30 per cent compared to the initial half.

The Legal Framework for Gig Workers

One of the chief characteristics of gig workers is that they are generally considered ‘independent contractors’ and not ‘employees’ in the traditional sense. In conventional understanding, an employee is one, who provides services for an employer, and the employer has control over what he will do and how. On the contrary, an independent contractor also works for employers, but here employer has control only over the work done but not the method of acquiring that. Thus, it would be important to note that most gig platforms have been careful to describe their drivers as ‘partners’ and not ‘employees’, classifying them under an ‘independent contractor’ category. Since gig workers do not fall under the purview

of labor laws, firms are not obligated to provide social security benefits that are generally available to employees.

Over the last few years, the size of the workforce in the Indian gig economy has been ballooning. As per ‘Online Labor Index’ created by Oxford Institute, India is leading the global gig space with over 24 per cent of the online labor market (Kässi, O. and Lehdonvirta, V. 2018). According to the NITI report, it is estimated that in 2020-2021, 77 lakh workers were engaged in the gig economy and they constituted 2.6 per cent of the non-agricultural workforce or 1.5 per cent of the total workforce in India. However, the fact that they continue to lack any form of social security benefits remains highly controversial. In 2019, the Ministry of Labor and Environment introduced the Code on Social Security. According to the new Code, the Central Government can formulate suitable welfare schemes for the unorganized sector from time to time on issues about life and disability, death, health and maternity benefits, old age protection, and so on.

However, the vast majority of gig workers fall under the unorganized sector, hence deprived of the ‘Employees Provident Fund’ and the Employees’ State Insurance Schemes. The new draft law proposed by the Ministry of Labor and Employment (2019) keeps gig work outside the traditional employer-employee relationship and defines a gig work platform as an online-based platform where organization or individuals can solve specific problems or provides services against payment. The code does envisage social security benefits for both the platform and gig workers. However, this still does not recognize gig workers as ‘employees’. Thus, although the code does not equate gig workers with traditional employees, it does offer them certain benefits as directed by the government. The gig platform and the workers are listed under ‘unorganized worker’. They are deprived of some social security benefits available to the organized sector. These benefits could range from insurance and maternity benefits to pension and gratuity, typically partially funded by the employer. Since the Wage Code 2019 does not apply to gig workers, it does not offer minimum wage requirements. The Social Security Code 2019 has met with mixed reactions. While the government’s move to introduce such a code is certainly a step in the right direction, the mechanism has been left mostly open-ended and has a long way to go.

II Literature Review

To understand the nature and impact of the gig economy worldwide, the study has explored existing literature in journal articles, newspaper and blog articles at a national and international level. The Technological Revolution, also known as the Fourth Industrial Revolution, has paved the way for significant changes in the nature of work. Djankov and Saliola (2018), in their article, present findings from the World Development Report (2019) and mention that as a consequence of the overall development and distribution of digital infrastructure, there is an enabling environment in which on-demand services can thrive.

Regarding the nature of Gig Work, Wood, et. al. (2019) posits that one of the differentiating factors of gig work is the platform-based ‘rating systems’. This type of management can be understood as a customer-based management strategy significantly different from the traditional Taylorist approach. The workers were given relative freedom to do as they wished, and the ‘control’ would be established once the work was completed rather than during it.

In another study by De Ruyter and Brown (2019), they state that the types of jobs available in this economy have low entry barriers. The authors address the issues and challenges associated with ‘traditional labor markets’. Gig workers appear to be predominantly young people who are either actively searching for employment or currently studying. Thus, gig work is more of a ‘temporary process’, until they get access to more standardized employment forms.

Several debates have surrounded the perceived advantages and disadvantages of gig work in the academic world. According to Kenney and Zysman (2020), the platform economy is “one in which social and economic interactions are mediated online, often by apps”. The ‘Utopian’ view is that emerging techno-economic systems allow society to be reconstituted, allowing producers to become ‘proto-entrepreneurs’, that can work on flexible schedules and benefit from these platforms. Conversely, the dystopian view states that new technology will result in undesirable consequences, with digital machines and artificial intelligence displacing work for a large popular population section.

Riley J. (2020), mentions the need for some regulation of the gig economy. According to his study, gig workers deserve basic market protections like any other employee. The existing regulatory initiatives mostly concern consumer protection issues and eliminate unfair competition among sectors. The paper posits that a potential solution would be to introduce a scheme that provides protections similar to those available to ‘Small Business Workers’ in unique commercial relationships. Another study by Gross, et. al. (2018) highlights the issues brought by the gig economy and its flexible employment patterns, emphasizing a need to understand and consider the view of work from a ‘well-being’ perspective, too, not just from an economic or employment law perspective.

Several web-based reports and news portals published reports on Gig economy. According to a Digital Future Society report (2019), India is the second- largest freelancer market, and this app-based technology does away with the middleman. Also, from the recruiters’ point of view, allowing gig work is cost- efficient. They generally do not provide paid leave or health care (and other securities) to gig workers as they do to full-time workers.

In another report published in LiveMint by Salman and Varsha (2019), Delhi has emerged as a leading destination for migrant workers joining the country’s tech-enabled gig economy, moving Bangalore to second place. Over the last eight years, two app-based cab service providers have collectively employed approximately 1.3 million drivers. Sindwani P. (2019), in her article published in Business Insider, mentioned that India is now the fifth largest country for ‘Flexi- staffing’. It added 1.2 million Flexi workers in 2015 and is predicted to employ

nearly three million by 2021. The joblessness among India’s urban educated and uneducated youth looks at the gig economy as a ‘stop-gap’ solution until market conditions improve. The report posits that several workers join the gig force as a last resort, not a permanent career choice. As a result of the lack of regulation, gig workers find themselves working too long hours to meet incentives put forth by the platforms. Indian HR firm TeamLease estimates that 13 Lakh people have added to the gig economy in the second half of 2018-2019, showing a 30 per cent growth relative to the year’s first half. Metros such as Delhi and Bengaluru emerged as the biggest drivers of this sector. The findings also reveal that 2/3rds of the workforce will be under 40 years.

Bhattacharya S. (2019) has published a summary report of a survey in the Economic Times. The survey was conducted by TimesJobs on June 20th, 2018, to study India’s emergence of the gig economy. Analysing 2100 HR professionals’ responses across different verticals, the study reveals a shift in how businesses operate. The gig economy benefits from cost-saving perspectives and also in terms of gaining competitive advantages. The increased dependence on a ‘fluid workforce’ disrupts the traditional permanent jobs model among organisations, large or small. According to the respondents, freelancers’ largest employers emerge from the IT and Tech, Media and Communications, and Events Sector. The report states that the main reasons for the rise in freelancing are the flexibility of work and easy access to technology, followed by a surge in mobility and work variety.

The rapid rise in popularity of app-based platforms has dramatically transformed consumer behavior. This shift in consumer behavior has also led to the simultaneous creation of new forms of employment to fulfill the demand. It is a phenomenon that is likely to have a profound impact on the nation’s social and economic fabric.

In the academic world, at the global level, there is a fair amount of literature regarding the perceived risks associated with gig work and a call to world governments for regulation and inclusion of labor laws to protect gig workers from potential exploitation. However, there is considerably less research done on the nature or impact of India’s Gig economy. Thus, the study aims to fill gaps by shedding light on the nature of gig work, the factors contributing to its rise, and its impact on the economy.

III Research Objectives

With this background, the present study has the following objectives:

● To understand the various factors that lead people to join this form of work

● To compare and contrast the perceived advantages and disadvantages, as well as the risks associated with the gig economy

● To analyse the ongoing debates surrounding the regulation of gig work and suggest potential solutions for policymakers

IV Methodology

The study is primarily qualitative. It also uses the Interpretivist approach, which states that multiple realities exist. These realities are constructed based on individual experiences. Thus, the study attempts to understand the phenomenon of gig work based on its stakeholders’ lived experiences. The study was conducted in February 2020. Since the choice of individuals who need to be interviewed is fixed ex-ante by judgment, the researcher uses non-probability sampling. To ensure that the respondents were direct stakeholders of the gig economy, the purposive sampling method (a type of non-probability sampling) is used, specifically, a homogenous sample. Face-to-face interviews were conducted using a semi- structured fixed interview schedule and additional follow-up questions based on the responses received.

In India, the gig economy primarily constitutes ride-hailing platforms and food-delivery platforms. Due to the paucity of time, the study focuses only on cab aggregators. It is an employer-employee study. The research includes interviews with employers and gig workers of the ride-hailing platforms of two cab-service providers. The names are changed to X and Y for privacy protocol. The interviews aimed to understand the socio-economic background, benefits, and challenges associated with this work. Twenty face-to-face interviews were conducted with the X and Y car service driver-partners in Bangalore. Apart from this, three interviews of individuals representing the companies were conducted. This was done to gain additional insights from industry experts regarding the functioning and future of gig work.

V Observations

For ride-hailing platforms such as X and Y, reduced costs are the primary factor causing their rising popularity. The platforms are aggregators of supply and demand, wherein the drivers are not company employees. They are independent contractors.

The structured questionnaire includes the respondents’ details, like age, sex, educational background, state of origin, the duration of their association with the cab aggregators, and questions about their previous jobs and experiences that led them to join the ride-sharing market.

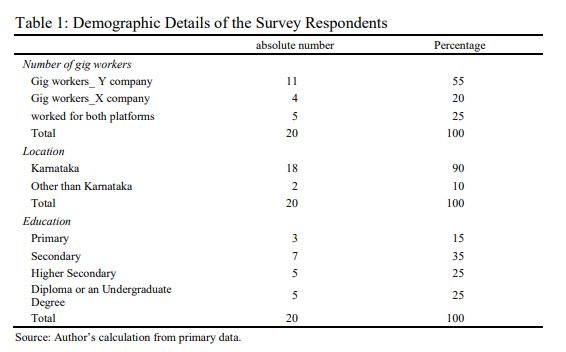

Table 1 summarizes the demographic details of the respondents. Out of the 20 interviewees, 11 individuals (55 per cent of the sample) were driver-partners of Y company. 4 individuals (20 per cent of the respondents) were driver partners of X company. 5 respondents (25 per cent of the sample) worked for both platforms. The study also includes three interviews of employees representing the companies. All 20 of the driver-partners interviewed were males. This finding coincides with the general cultural setup in Indian society, wherein females joining gig form of work is rare due to a host of taboos and safety concerns. 6 out of 20 (30 per cent of the driver-partners) interviewed fell under 18-25 years age bracket. 12 out of 20 (60 per cent of the respondents) were in the 26-35 years age cohort, and the remaining 2 respondents (10 per cent of the driver-partners) were in the bracket of 36-45 years. Apart from the structured questions about their age, the respondents were also asked to gauge a driver partner’s average age. It was interesting to note that most respondents stated that this work welcomes people of all age groups. However, they gauged the average age between 25 to 35 years. Of the 20 respondents, 18 comprised 90 per cent of the sample from Karnataka. Two respondents hailed from the State of Assam. Most respondents were from small towns in Karnataka, Bangalore’s peripheries, namely Ramanagar or Hubli. Three out of 20 (15 per cent of the respondents) attained primary-level education. On the other hand, seven respondents (35 per cent) had attained secondary-level education. Five out of 20 (25 per cent of the respondents) completed the secondary level (PUC), while five respondents (25 per cent of the respondents) held a Diploma or an Undergraduate Degree.

According to the X company representative- “Initially, the drivers used to be from the big cities like Bangalore or Bombay. However, this has changed

over the last couple of years. The demand is very high, but the supply does not match it. We now go into smaller towns of Karnataka like Mysore or Hubli, and recruit individuals from there”.

When the ride-hailing platforms first came about in India, the driver partners’ incentives were very high. As a result, many individuals left their traditional employment to enter this new sphere of work. However, over the last couple of years, the companies have drastically rolled back on the gig workers’ incentive. Thus, a supply-side deficit came about. To meet the rising demand, cab aggregators ventured into smaller towns and rural areas to recruit driver-partners. Therefore, this has also led to inter-state migration. In India, the Gig Economy comprises mainly informal or blue-collar labor. Thus, it is characterized by low barriers at the entry level. The findings of the interviews highlighted that educational qualifications are not a barrier for such jobs. While some respondents held a Diploma, others did the same job without completing their secondary education level.

Here we have summarized their responses under various headings-

Experience with the Gig Platforms

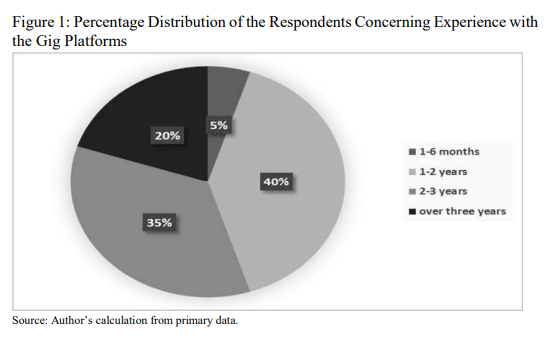

Figure 1 gives a pictorial presentation of the respondents’ experience with the Gig Platforms. Out of the total respondents, one respondent (five per cent of the total respondents) fell under the category of 1-6 months of work experience. Eight respondents, comprising 40 per cent of the total pool, claimed to have 1-2 years of experience. On the other hand, seven respondents (35 per cent), had 2-3 years of experience as a gig worker. Lastly, four out of the total (20 per cent of the respondents) had over three years of experience with the ride-hailing platforms.

Previous Employment

The respondents were asked about their past jobs before entering the gig market. 8 out of 20 (40 per cent of the respondents) stated that their previous jobs included some form of driving. A trend in the market is that individuals who join the cab aggregators generally have some driving experiences for private parties or as auto, bus, or truck drivers. Four respondents came from other industries, previously working in occupations such as Security Guard, Electrician, Book Salesman, etc. Some respondents revealed additional information about their journey to the gig market. A few of them stated that they had vehicles back in their hometowns, in the rural parts of Karnataka, and they saw this as an opportunity to improve their standard of living. A couple of them stated that they did not view this as a permanent career choice and would only continue working here until they had paid off certain debts or loans. One of the respondents mentioned that he held a Diploma in Computer Science. He had worked in the formal sector, but Demonetization had negatively impacted his career. He decided to join the Y company as a driver-partner while looking for alternative career options.

Is This Your Primary Source of Income?

The respondents were asked if they regard their revenue from the gig platforms as their primary income source or merely an additional or supplementary source. This also gives insights into the potential of gig work as a permanent career path. 16 out of 20 respondents (80 per cent) considered this particular job as their primary and only income source. Two respondents indicated that it is a part-time job. Another two noted that this is their primary income source, but they have other supplementary sources.

The next segment of the interview comprised questions about a gig worker’s daily routine from the X and Y company. The driver-partners were asked questions about their daily routine, working hours, breaks, holidays, and support provided by their companies in the form of medical compensation or otherwise.

Working Hours and Breaks

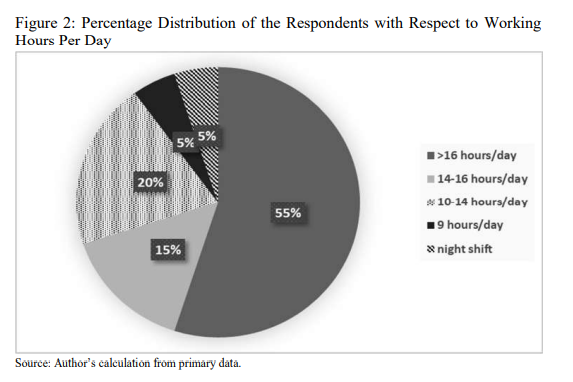

Flexibility is one of the chief characteristics of gig work; workers can choose the type of work they wish to take up, the time and place factors, the amount of work they undertake, and how they complete tasks. This sense of perceived autonomy and freedom primarily attracts individuals to the gig economy. According to De Ruyter, et. al. (2018), there are challenges associated with the ‘transitional labor markets. Gig workers appear to be predominantly young people actively engaged in the job search or are currently studying. The evidence suggests that gig work is more of a ‘temporary process’ than becoming a sustainable career choice until they can access a more standard form of employment. Figure 2 provides information on the working hours per day of the respondents.

11 out of the 20 respondents (55 per cent) stated that they worked 16 hours or more daily. Three respondents (15 per cent of the pool) indicated that they followed schedules that were over 14 hours every day. Four out of the 20 respondents (20 per cent) stated that they worked for over 10 hours a day. One respondent said he generally preferred to work the night shift, starting work at midnight, as the incentives are higher. One respondent stated that he performed a 9-hour schedule. 19 of the respondents start their working days before 8 am, with many starting as early as 4 am. They generally prefer early morning and late-night rides to the airport or other long-distance rides because the incentives are higher during these hours. 16 out of 20 respondents (80 per cent) stated that their daily schedules ended after 10 pm.

It should be noted that these working hours include the breaks taken by the driver-partners. The cab aggregators give driver-partners the freedom to take as many breaks as they wish. On average, the respondents said they break for about two hours a day. Thus, it is evident that a gig worker’s average life on these ride- hailing platforms is indeed strenuous. The majority of them work incredibly long shifts to make ends meet.

Meals, Holidays, and Medical Compensation

The respondents stated that the platforms do not provide meals or cover for the driver-partners additional expenditures. The companies do not cover the amount

spent on meals, diesel/petrol, or other miscellaneous costs. These are extra expenses that must be deducted from their regular earnings.

A testament to the ‘flexibility’ of the gig economy, the platforms do not provide holidays of any kind. The decision to choose the number of working days remains entirely up to the gig worker. National holidays and strikes that would generally apply to other sectors do not apply to the gig economy. During his interview, the X company representative stated that holidays are the busiest year for the gig economy. Most driver-partners interviewed said they take 2-4 days off a month.

The interviews’ findings and existing literature reveal that gig workers do not receive any form of medical compensation or other social security benefits.

A response by X company representative – “I don’t think that the gig workers have an issue with the functioning of the gig economy. However, along with the gig economy comes a lack of insurance and other social security benefits. Here in India, the fact of the matter is that they are not used to it anyway. The situation is different in Western countries where there is a sense of awareness, probably due to their educational backgrounds, wherein they demand these securities. So if you were to ask me if our driver-partners are missing out on anything, I don’t think they are, because they haven’t gotten it before, so it’s not being taken away from them”.

Wages and Incentives

In the gig economy, employees are not paid fixed salaries. Gig workers are not treated as salaried employees but rather as independent contractors paid by the ‘gig’. Thus, the driver-partners at X and Y companies have the discretion to decide their earnings by choosing their working conditions.

According to X company representative- “There is no base salary. There are two types of driver-partners, the first are drivers of our leased cars, and the second type are those that have their car or work for a private company”.

The interviews findings from the interviews reveal that the gig workers receive payment daily (as is the case with X company), or a weekly (as is the case with Y company) basis. Some respondents stated that they preferred this form of payment because their accounts are credited promptly rather than waiting for monthly wages as in traditional jobs.

The primary driving force attracting individuals to join these platforms are the incentives. When the cab aggregators first came about, the driver-partners had the opportunity to earn up to a lakh a month through incentives. This was seen as revolutionary, causing several individuals to leave their traditional jobs and shift to this market. Although the incentives have been rolled back heavily over the last couple of years, many still consider it a lucrative career option. The incentives provided by the platforms are primarily monetary. They are based on factors such as; the number of rides completed, distance covered, etc. Through surge pricing, there are also higher incentives for rides during the peak hours. Thus, these factors

are taken into consideration by the platforms while providing incentives. Also, incentives are higher for long-distance rides and night shifts.

According to the X company representative- “All the gig platforms in India started with heavy incentives. The driver partners were happy, as they were earning high amounts. However, over the last couple of years, the companies began bleeding out, so we had to make a tough decision to roll back on incentives. The incentives have now gone down significantly. 2-3 years ago, the driver partners viewed this as a sustainable career path, but now they have to work extremely long hours to make ends meet. Normally you tend to grow upwards in your career, and not the other way around. But I think people need to understand that without these platforms, they wouldn’t have a job at all. What makes them stay? – Well, what else can they do? Most of them have started their careers as drivers; where do they go from here? Unfortunately, a significant number of them do not possess additional qualifications, or adequate educational backgrounds, because it will be difficult for them to get out of this field altogether”.

Factors that Motivated You to Join this form of Employment

(Y company representative) – “The social group of Y company drivers in India sees themselves grow as independent small business owners. This is driving micro-entrepreneurship within the system. They don’t see it as temporary freelance jobs but as full-time livelihoods. This system has brought a formalized structure in the economy by ensuring they get paid a fixed per centage. The driver partners are moving to bigger cities and can better their quality of life and their families. This is evident from the growing popularity of the profession. The driver-partners themselves decide the working hours and breaks. They are running their own business and are equally involved in making them as success as we are. We are just the enablers here”.

Several pull factors attract individuals to the gig economy. In a developing country like India, individuals working in the gig economy are generally willing to overlook certain negative factors, such as the perceived risks and uncertainties, and focus on the perceived advantages, such as increased flexibility, autonomy, and higher income. Ride-hailing services in the form of taxis or autos are certainly not recent. However, platforms such as X and Y allow drivers to increase their earnings using multiple short rides. This is one of the distinguishing features of the platforms.

According to Babu (31) (name changed), a driver-partner of Y company, “We are in a partnership with Y. We get good work. If I worked as a driver in a private company and got a 20 km away job, the drive back would be empty. But Y company allows for short trips. In this way, I can save on diesel. Through the weekly payment system, I can maintain my car better than I could have if I were working for a private company, so over all, I think this is a more profitable business”.

Similarly, Lokesh (29) (name changed), another driver partner of Y, states, “I work as a private company driver as well. I think working for Y is better during

peak hours because they have surging prices, so you can make more profits compared to when you work as a driver in a private company”.

Most respondents stated that the primary reason to join this form of work was the potential to earn a higher income. Although they have taken a massive dip over the last couple of years, gig workers remain in this form of work. Some of them continue to stay because they are satisfied with the earnings, while others lack viable alternatives. Other respondents stated that flexibility was one of the primary motivators for joining this form of work. Apart from this, some respondents said their motivation was that they had a vehicle of their own, so they believed this work would be profitable. Some stated that they chose this profession as there are no viable alternatives. In India, the unemployment scenario is quite abysmal. Every year, almost four million individuals join the existing workforce. Thus, gig platforms play a crucial role in providing employment.

Challenges Associated with Gig Work

(X company Representative) “I don’t think they have an issue with the gig economy. However, along with the gig economy comes a lack of insurance and other social security benefits. But, here in India, they are not used to it anyway. So, if you were to ask me if they are missing out on anything? I don’t think they are because they haven’t gotten it before, it’s not being taken away from them. Their main issue is the reduction of incentives, not the functioning of the gig economy. All the gig platforms in India started with heavy incentives. The drivers were happy; they were earning high amounts. But the companies began bleeding out, so we had to roll back the incentives. The driver-partners have complained about it, and it is a fair argument; their frustrations are understandable. But it is a tough balance at the end of the day”.

The Paradox of Flexibility in Gig Work

The chief characteristic of gig work is the perceived benefit of ‘flexibility’. However, in several situations, this flexibility does not make the lives of gig workers easier but adds to the risk of their work and uncertainty.

Rajesh (name changed) (23), a driver-partner of Y, states- “I would like to have fixed timings and a routine, but I have not been able to find that type of work. In my opinion, fixed timings are better because I get to return home and leave regularly. With this type of work, the income is good, but there is uncertainty. Every day I sleep in a different location while taking breaks, wherever I can find shade. This is not something I would like to continue with.”

Lack of Protection for Gig Workers

The Gig Economy remains mostly unregulated. Thus, gig workers lack a sense of protection or safety net generally available to employees in a traditional setup. While gig platforms strive to ensure maximum customer satisfaction, the gig

workers’ woes often go unnoticed. In the interview, the respondents were asked to share experiences highlighting certain challenging or negative aspects of their work.

Sarvesh (name changed), (37) a driver-partner of Y, states- “I would not say I am against the rating mechanism; however, sometimes it is very arbitrary. For example, if a customer wants to smoke in the car and I do not permit it, I am immediately given a negative rating. This reduces my incentives.” Similarly, Sriram (name changed), (40) a driver-partner of both X and Y, states- “The company does not care for the drivers; it only values its customers. Sometimes we get delayed due to traffic conditions. It is out of our control, but we still get negative ratings, and there is nothing we can do”.

One of the prominent and novel characteristics of gig platforms is the ‘Rating’ feature. It allows the gig workers to be directly answerable to the consumer and thus does away with certain ‘employer-employee’ dynamics. Although most respondents expressed that they liked the rating feature, some expressed concerns about it being too arbitrary.

Regarding driver safety, Ramprasad (29), a driver-partner of X, said, “All the details of the drivers are taken for safety measures. But what about the customers? Sometimes, they take advantage of the drivers, especially drunk ones. No details of the customers are asked apart from the mobile number, and the drivers continue to be blamed for everything”.

According to the X Representative- “There are many ways that the driver- partners can break the contract or get suspended. When we receive a complaint, the first thing we do is suspend the driver. At this stage, it does not matter if the driver-partner was really at fault, but this is the protocol we follow. Following this, an investigation is conducted, and we take a call on the next step. The driver partners don’t like it; they are always persecuted. If anything goes wrong, they are always at fault. I can understand their frustrations. However, our priority is to ensure the safety of the customer.”

The Mental Strain of Gig Work

Along with autonomy and flexibility, gig work also comes with high risks and uncertainty. The proponents of gig work have mainly overlooked the mental strain of working under such extreme conditions. Several respondents stated that this work could not be considered a sustainable career choice because of the uncertainty that comes with the nature of the work. The long working hours and the conditions under which gig workers are made to work are mentally taxing. In a city like Bangalore, driving in traffic conditions for over twelve hours a day can cause high mental strain and frustration. These are aspects that often go unnoticed.

(X Representative) stated – “The mental strain of the drivers is a big concern for us. Driving in cities like Bangalore, with traffic conditions, is highly irritating. Mentally, they become frustrated, and this could lead to other issues. We try to address this by providing counselling sessions for the driver-partners, but this is not as effective as we would want t it to be.”

Summary of Findings

Some of the chief characteristics of gig work are flexibility and autonomy. Gig workers are free to choose the type of work they wish to take up, the time and place factors, the amount of work they undertake, and how they complete tasks. A testament to the flexibility of gig work, there is generally no fixed salary that employees pay to the workers. They are paid as independent contractors for each ‘gig’ undertaken.

Although the perceived benefits of the level of flexibility and autonomy are high, it is not an entirely rosy picture. Unlike traditional employees, one of the most controversial aspects of gig work is that companies do not provide any social security benefits to gig workers. The lack of financial stability and security is one of the main concerns of the gig worker. Another inference from the interviews was the paradox of ‘flexibility’ provided by gig work. With over 50 per cent of those interviewed stating that they work 16 hours or more daily (including breaks), it is evident that a gig worker’s average life in these ride-hailing platforms is indeed strenuous. The majority of them work incredibly long shifts to make ends meet. The proponents of gig work appear to have overlooked the mental strain of working under such extreme conditions. Several respondents stated that this form of work could not be considered a sustainable career choice because of the uncertainty.

Lastly, regulating the gig economy remains a hotly debated issue in the academic world. The free market forces of supply and demand primarily run the gig economy. While proponents of gig work argue that this will lead to sustained growth, critics think that a complete lack of regulation could lead to the potential exploitation of gig workers.

II Conclusion

The gig economy is a rapidly growing phenomenon. It has dramatically changed employment patterns worldwide, with an increasing number of people choosing to do away with traditional forms of work and become ‘micro-entrepreneurs’. It is a phenomenon that affects so many individuals’ lives and has wide-reaching impacts on the economy. Therefore, the government must take specific initiatives to create a conducive environment wherein all the economic stakeholders can thrive.

Gig workers are entitled to the best of both worlds- flexibility and benefits. As expressed by the Uber CEO (Mr. Dara Khosrowshahi), the current system is binary. When a company provides additional benefits to independent contractors, they become less independent. Similar concerns were echoed regarding the Indian Social Security Code 2020 formulated by the Central Government. The social fund proposed by the Code could reduce the earnings of platform workers. The cost of other social security benefits will reduce in-hand income and could also lead to selective hiring. A proposal put forward by Mr. Khosrowshahi is the establishment

of benefit funds that give workers the cash they can use for the benefits they need like health insurance or paid time off (The New York Times, 11th August, 2020). Independent workers in any state that passes the law could take money out of every hour of work they put in. All gig platforms would also be required to contribute towards the funds. The proposal is initially meant for California and hopes to be implemented across countries.

Taking this one step further, another potential solution could include platform users’ contributions. This would be a set-up wherein the welfare costs are defrayed among the platforms, government, and customers. Platform users would be liable to pay a small amount in the form of welfare payments at the end of every ride. This, along with contributions from the government as well as gig platforms in a single pool, could eventually form a social fund for the benefit of gig workers. Nonetheless, this would have to be implemented transparently with norms in place, not to be misused by the companies.

The fund can be used to provide welfare to gig workers in the form of health insurance and other long-term benefits. The need of the hour would be to tread a middle path that accounts for the security of gig workers whilst allowing gig platforms to flourish and provide employment opportunities.

References

Bhattacharya, S. (2019, August 13), How Gig Economy is Becoming a Key Part of India Inc’s Strategy, Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/company/corporate- trends/gig-projects-taking-over-corporates-and-professional-services-firms/articleshow

/70651920.cms

De Ruyter, A. and M. Brown (2019), Regulation and the Lived Experience of the Gig Economy, In the Gig Economy (pp. 55-78), Newcastle upon Tyne: Agenda Publishing, Retrieved February 27, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvnjbff3.6

De Ruyter, A., M. Brown and J. Burgess (2018), Gig Work and the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Conceptual and Regulatory Challenges, Journal of International Affairs, 72(1): 37-50, doi:10.2307/26588341

Digital Future Society (2019), The Future of Work in the Digital Era: The Rise of Labour Platforms, file:///C:/Users/nsing/Downloads/The_future_of_work_in_the_digital_era.pdf

Djankov, S. and F. Saliola (2018), The Changing Nature of Work, Journal of International Affairs, 72(1): 57-74, doi:10.2307/26588343

Donovan, S.A., D.H. Bradley and J.O. Shimabukuro (2016), What Does the Gig Economy Mean for Workers? Congressional Research Service Report, 7-5700, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc

/R44365.pdf

Gross, S., G. Musgrave and L. Janciute (2018), What’s the Issue? In Well-Being and Mental Health in the Gig Economy: Policy Perspectives on Precarity (pp. 7-11), London: University of Westminster Press, Retrieved February 27, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv5vdf26.4

Kässi, Otto and Lehdonvirta, Vili (2018), Online Labour Index: Measuring the Online Gig Economy for Policy and Research, Working paper, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3236285

Kenney, M. and J. Zysman (2020, February 18), The Rise of the Platform Economy, Retrieved from https://issues.org/the-rise-of-the-platform-economy/

Khosrowshahi, D. (2020), Our Business in India is in Very Solid Shape: Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, October 12, https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/our- business-in-india-is-in-very-solid-shape-uber-ceo-dara-khosrowshahi-120101200019_1.html

Manyika, J., S. Lund, J. Bughin, K. Robinson, J. Mischke and D. Mahajan (2016), Independent Work: Choice, Necessity and the Gig Economy, Mckinsey Global Institute, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/employment-and-growth/independent-work- choice-necessity-and-the-gig-economy#

Radhakrishnan, Ananya (2020), The Future of India’s Gig Economy, https://www.indianfolk.com/future-indias-gig-economy/

Riley, J. (2020), Brand New ‘Sharing’ or Plain Old ‘Sweating’?: A Proposal for Regulating the New ‘Gig Economy’, In Levy R., M. O’brien, S. Rice, P. Ridge, and M. Thornton (Eds.), New Directions for Law in Australia: Essays in Contemporary Law Reform (pp. 59-70), Australia: ANU Press, Retrieved February 27, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable /j.ctt1ws7wbh.9

Salman, S.H. and B. Varsha (2019), Delhi, and Not Bengaluru, is the Place to be for Gig Economy Workers, https://www.livemint.com/companies/start-ups/delhi-and-not-bengaluru-is-the- place-to-be-for-gig-economy-workers-1555013405684.html

Sindwani, P. (2019), 6 Million Indians will be in the Gig Economy within Two Years – That’s Nearly Twice the Current Size, Business Insider, India, https://www.businessinsider.in/6-million- indians-will-be-in-the-gig-economy-within-two-years-thats-nearly-twice-the-current- size/articleshow/69854133.cms

Wood, A.J., M. Graham, V. Lehdonvirta (2019), Good Gig, Bad Gig: Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy, Work, Employment and Society, 33(1): 56-75.