Intra-Industry Trade in Manufactured Goods: A Case of India

March 2023 | Manmohan Agarwal and Neha Betai

I Introduction

For a long time, trade between any two countries was explained by the Ricardian/Heckscher-Ohlin models, which theorised trade to be driven by differences in technology or factor endowment. The classical and neo-classical models emphasised inter-industry trade, where each country would specialise in the production of a particular commodity (the assumption here was that all processes required for the production of a commodity would be performed in the country) and would then exchange it with its trading partner. However, in the post- war period, it was observed that trade between economies was no longer the cheese for wine type as believed by theorists. Instead, the exchange between commodities

Manmohan Agarwal, Adjunct Senior Fellow at RIS, Email: manmohan44@gmail.com

Neha Betai, Academic Associate, Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore 560076, Karnataka, Email: neha.betai@gmail.com

The authors would like to thank all the participants of the conference on Economic Theory and Policy organised in March 2021, especially Dr. Rudrani Bhattacharya, for their comments on the earlier version of the paper

comprised of goods that belonged to the same category. This pattern of exchange was termed as Intra-industry trade (Balassa 1966).The initial research in intra-industry trade (IIT) focussed on the trading patterns of developed economies. Economists such as Verdoorn (1960) and Balassa (1963) observed the changes in patterns of trade in European countries after the formation of Benelux and the European Economic Community (EEC). They found that developed countries showed an increasing proportion of intra- industry rather than inter-industry trade. This pattern was repeatedly observed in most developed countries.

The same pattern, however, was not observed in developing countries. Few researchers found evidence of IIT between developing countries and between developed and developing countries. The notion that developing countries primarily engaged in inter-industry trade stemmed from two beliefs: the inability of developing countries to exploit economies of scale and the significant differences in factor endowment between countries, especially in the North and the South, constrained IIT. Despite such beliefs, some economists showed the presence of IIT in trade in manufactures between developing countries (Balassa 1979). IIT was found to be high between developing countries and between developed and developing countries. Both studies found that regional integration in the form of trade blocs and bilateral agreements played an essential role in increasing IIT. Moreover, in recent years, there have been a large number of studies that show theoretically and empirically the existence of IIT between developing countries and their trading partners (Manrique 1987, Globerman 1992)

This paper explores the nature of trade between one of the largest developing countries, India, and its 15 most significant trading partners. These countries were chosen because over half of India’s trade is accounted for by them. The objective is to identify the factors that drive IIT in India. However, unlike the other studies in the area, we do not simply calculate IIT for all manufacturing products. Instead, we stick to merchandise trade in chemicals and manufacturing products (groups 5 to 8 in SITC Rev. 3.), and we categorise these products into groups based on their technological content. The categorisation of these products is done using the Lall Classification, which classifies products into ten separate groups. We conduct this exercise to understand better the type of goods in which India exhibits higher IIT and the factors that influence IIT in different categories.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section II, we look at the literature on IIT, focusing on studies done in the Indian context. In Section III, we describe the methodology adopted for empirical analysis. Next, in Section IV, we provide a background for India’s trade, specifically IIT. In Sections V and VI, we delve into the empirical analysis and the discussion of the results. Section VII concludes the paper.

II Literature Review

Beginning with Verdoorn (1960), several studies found that countries increasingly exhibited specialisation within the same category of goods being traded (Balassa 1963, Kojima 1965, Grubel 1967); this pattern of trade was termed Intra-industry trade (Balassa 1963). These findings were contrary to traditional theories of trade, which predicted that countries would specialise in different goods (depending on their comparative advantage or factor endowments) and trade with each other to enjoy gains from trade. Even before Verdoorn (1960), Leontief (1936) had indicated that the HO theorem failed to explain the trade pattern of countries with similar factor endowments. The advent of studies on IIT further extended support to his point. The book by Grubel and Lloyd, “Intra-Industry trade”, published in 1975, dealt with aggregation and measurement of IIT and provided additional impetus to studies in this field.

The initial studies on IIT were largely empirical with little theoretical backing, which was initially provided by Krugman (1979). Krugman (1979) shows that trade in similar but different commodities between countries was induced by two factors, economies of scale in production and consumer’s love for variety, which also gave rise to GFT from IIT. Subsequent studies by him found that as countries become similar in their endowment, IIT between them increases (Krugman 1981). Linder (1961) had put forth a similar hypothesis which suggested that similarity in demand patterns would increase the volume of reciprocal trade between economies in differentiated goods. Lancaster (1980), too, argues that countries with the same factor endowments would exhibit pure IIT. As the extent of similarity between endowments reduces, IIT would reduce. Helpman (1981) measured similarity as an absolute difference in income between countries and showed the negative correlation between similarity and bilateral IIT.

Since Krugman, subsequent theoretical and empirical work has tried to determine factors other than similarity (in factor endowment or incomes) that influence IIT. Factors such as the size of the economies (Helpman 1987), regional integration (Balassa, 1979), comparative advantage in production were also said to play an essential role, as were gravity variables such as distance between the economies (Helpman 1987).

Given this background of literature on IIT, we now turn to the literature on India’s pattern of trade. Several studies have repeatedly examined the presence of IIT between India and its trading partners, the distinctiveness of the patterns and the determining factors.

First and foremost, trade liberalisation has proved to be an essential factor in increasing IIT. Veeramani (2002) showed that trade liberalisation in India since the 1990s has been biased towards IIT. He argues that this increase in IIT is a manifestation of resource re-allocation within industries. Similarly, Burange and Chaddha (2008) found that reducing trade barriers and efficient allocation of resources gave rise to specialisation within unique varieties of goods and hence increased IIT. A recent paper by Aggarwal and Chakraborty (2019) finds that

multilateral reforms and trade liberalisation have enhanced India’s IIT at aggregate and sectoral levels.

Coming to the impact of free trade agreements, the evidence so far unilaterally dictates that FTAs and RTAs have enhanced IIT in India. Aggarwal and Chakraborty (2019), Das and Dubey (2014) find that India’s signing of FTAs and bilateral agreements with trade partners have been instrumental in driving IIT. Varma and Ramakrishnan (2014) show that SAFTA and agreements with ASEAN members have not only influenced manufacturing IIT but has also increased the extent of IIT in agri-food products. The studies argue that further integration will help in sustaining such trade flows. Next, studies have tried to examine whether the rising IIT results from an increase in exports or imports. Veeramani (2002) shows that the rising exports by India have contributed to the increase in IIT. In an examination of the Indian textile industry, Bhadouria and Verma (2012) show that IIT in textiles has gone down since the start of the 21st century due to increased net exports. On the other hand, Bagchi (2017) found that it is the rise in imports that has been responsible for rising IIT.

Examining the more traditional factors driving IIT, such as similarity and factor endowment, the literature shows exciting results. According to the theory on IIT, India’s IIT should be higher than other developing countries due to similarity in income and factor endowments. However, Veeramani (2002) and Srivastava and Medury (2011) find that India has a higher proportion of IIT with developed economies, i.e., highly dissimilar economies. They attribute this finding to a higher share of vertical IIT in India’s trade.

Lastly, factors such as distance, India’s increasing income and economic size, efficiency, relative comparative advantage are also said to play a positive and significant role (Srivastava and Medhury 2011, Bagchi 2017, Aggarwal and Chakraborty 2019). An increase in income and size of the economy increase the demand for products giving rise to IIT, whereas RCA indicates efficiencies in production which influences the supply of products.

III Methodology

In this paper, we aim to study the patterns of IIT between India and its top 15 trading partners. These 15 partners are Bangladesh, Belgium, China, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Malaysia, Nepal, Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States and Vietnam. We calculate IIT between India and its partner countries using the Grubel-Llyod Index. The formula used is as follows

∑i(𝑋j + 𝑀j) − ∑i |𝑋j − 𝑀j|

𝐼𝐼𝑇j = i i i i

∑i(𝑋j + 𝑀j)

i i

Where i represents the industries at the third level from groups 5 to 8 in SITC Rev 3, and j is the partner country.

In the formula, |𝑋j − 𝑀j| measures the inter-industry trade in each industry,

i i

which is then removed from the total trade, (𝑋j + 𝑀j) between the economies.

i i

Thus, what we are left with is the intra-industry trade in the industry. The economy- wise measure of IIT is then obtained by averaging each industry measure across the n industries. The weights used are the relative shares of industry exports and imports. The most essential feature of the measure is that it was derived by matching the value of exports and imports in each industry and then averaging these measures (Llyod 2002). Studies have shown that the index is an appropriate measure in studies that aim to explain comparative advantage, specialisation and predict patterns of trade. However, there are arguments that this index is downward biased, since it does not adjust for aggregate trade imbalances, which tend to be large, mainly when applied to bilateral flows. Despite this shortcoming, the index remains a popular measure of IIT used in studies.

The data for imports and exports for the study was collected from WITS. Unlike other studies that have looked at the manufacturing sector or specific sectors of an economy, we focus on the products from SITC groups 5 to 8. Group 5 consists of Chemicals, Groups 6 and 8 comprise all manufactured goods, whereas Group 7 is made up of machinery and transport equipment. Additionally, to better understand India’s trade pattern, we divide these products into ten technological groups. The categories are Primary Products, Resource-based Manufactures (RBM): Agro, RBM: Other, Low Technology Manufactures (LTM): Textile, Garments and Footwear, LTM: Other Products, Medium Technology Manufactures (MTM): Automotive, MTM: Process, MTM: Engineering, High Technology Manufactures (HTM): Electronic and Electrical (E&E) and HTM: Other. The categorisation of products into the groups was provided by Sanjay Lall and is often known as the Lall classification.

By dividing products into these categories and analysing the categories individually, we can determine the differences in which factors influence the trade patterns in each type of product and thus have specific policy recommendations for them.

The time period chosen for analysis is 1988 to 2015. This time-period captures the pre- and post-liberalisation periods, as well as the period during which India began entering into regional trade agreements and started experiencing the repercussions of it.

IV Background Statistics

In table 1, we show some details of India’s trade. We find that India’s trade with the world has grown quite rapidly. The growth in exports and imports has been close to or over ten per cent in each period. When we look at the share of India’s top 15 trading partners in exports and imports, we find that over half of India’s

exports are destined for these locations. Similarly, over 40 per cent of India’s imports originate in these countries.1 An interesting trend here is that after the global financial crisis, the share of India’s exports to these countries has reduced, whereas India’s imports from the same countries have increased. When we focus only on groups 5 to 8, we find the same growth patterns. However, the share of the top 15 countries in these commodities is much higher. Over 60 per cent of total trade in these commodities has been concentrated to India’s top 15 trading partners in recent years.

Of the 15 countries in consideration, India has trade agreements (either directly or through a more comprehensive group agreement) with five of them, Bangladesh, Nepal, Singapore, Vietnam and Malaysia. All agreements were either signed or came into force after 2005.

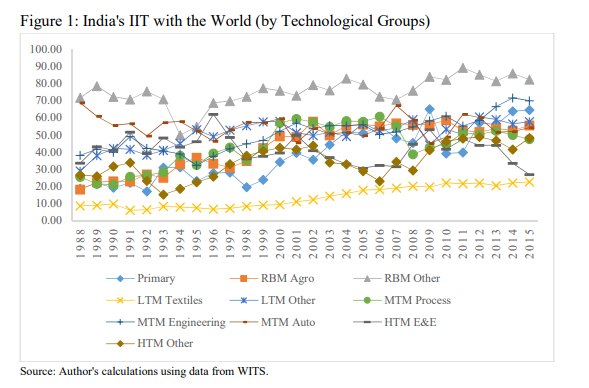

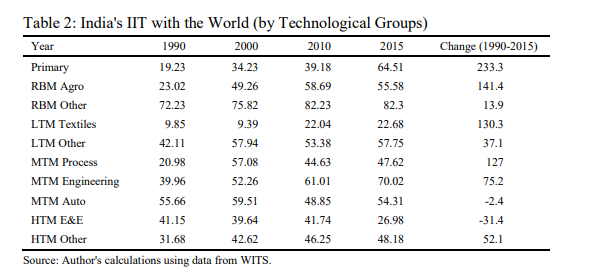

As seen from Figure 1 and Table 2, IIT for the products under consideration has increased for all ten categories since 1990 except HTM E&E. India has the lowest IIT in LTM textiles whereas proportion of IIT is the highest in RBM Other, followed by MTM Engineering. Primary products have seen the highest increase in IIT since 1990. We also find that no two groups follow the same pattern. Moreover, the increase in IIT has not been constant. There have been sudden ups and downs, especially around crisis periods such as the Asian Financial Crisis and the Global Financial Crisis. For instance, IIT in MTM Automotive declined after the GFC while it increased in HTM other. Lastly, we see that out of the ten categories, IIT is the dominant form of trade for approximately 7 of them in 2015 compared to just 2 in 1990.

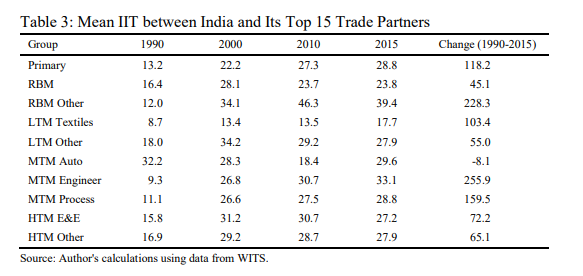

When we look at the mean IIT between India and its top 15 trading partners (Table 3), we see that mean IIT has increased for all groups except MTM Auto. Just as in India’s IIT with the world, the lowest IIT is in LTM Textiles while the highest is in RBM Other. We find that the average proportion of IIT with these 15 countries is much lower than India’s IIT with the world. Moreover, these numbers

indicate that a large proportion of India’s trade with its major trading partners can still be categorised as inter-industry rather than intra-industry trade.

V Empirical Analysis

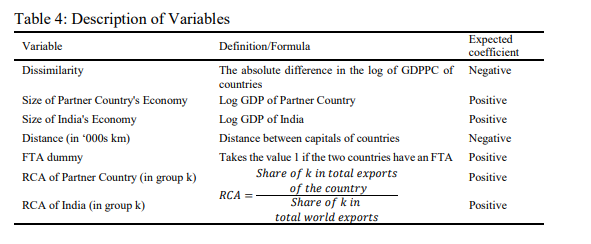

The brief literature in Section II gave us an overview of the factors that theoretically and empirically affect IIT. This section uses these factors to determine their impact on India’s IIT with its partners in different product categories based on their technology. For this purpose, we employ the gravity model wherein we model IIT as a function of the distance between the two countries and the sizes of the two economies. We expect the coefficient of the distance variable to be negative and the size of the two economies to be positive. Next, we include a measure of dissimilarity, measured as the absolute difference between per capita between the two economies. As per the theory, the dissimilarity should have a negative coefficient. However, past literature on India indicates that dissimilarity may also be positive. We also include the variables that measure the RCA of India and its partner country in the industry. If RCA is positive, then IIT is trade creating and enhances efficiency. We expect it to be positive. Lastly, we include dummy variables that indicate whether India has an FTA with the partner country. We also allow for country fixed effects to capture country-specific factors that might be influencing IIT.

| j |

𝐼𝐼𝑇k = 𝛼 + +𝛽1𝐷𝑖𝑠𝑠𝑖𝑚𝑖𝑙𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑡𝑦 + 𝛽2𝐿𝑜𝑔(𝐺𝐷𝑃j) + 𝛽3𝐿𝑜𝑔(𝐺𝐷𝑃India)

+ 𝛽4𝐷𝑖𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒 + 𝛽5𝐹𝑇𝐴 + 𝛽6𝑅𝐶𝐴k + 𝛽7𝑅𝐶𝐴k

j

+ 𝐶𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑦 𝐹𝑖𝑥𝑒𝑑 𝐸𝑓𝑓𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑠 + 𝜀

India

Where j is the partner country, and k represents the technological grouping.

We run this equation for each of the ten technological groupings (k). Since our dependent variable, IIT, measured using the Grubel-Llyod Index, is a continuous variable bounded between 0 and 1, we employ the fractional Probit response model for panel data using QMLE. This estimation technique, developed by Papke and Wooldridge (2008), has two merits over the traditional OLS regression estimates. First, if the dependent variable takes the value 0, we do not encounter the missing data problem. Second, we can estimate the marginal effects of the independent variables on the dependent variable. All variables were checked for stationarity and stationarized before running the regression.

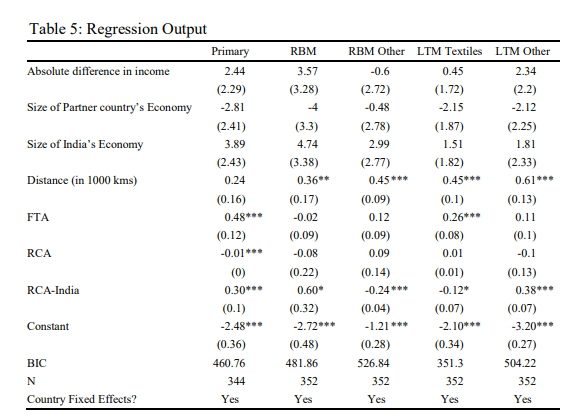

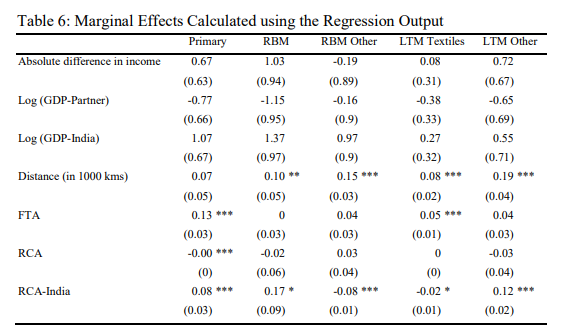

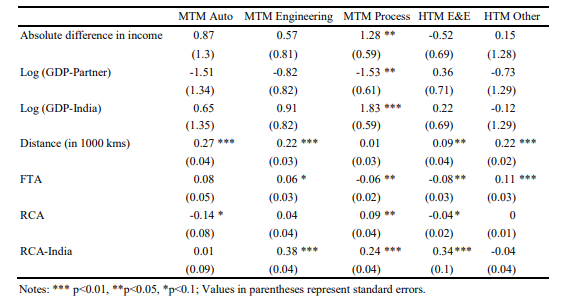

The results from the regression analysis and the estimated marginal effects are shown in Tables 5 and 6, respectively.

The results from our regression analysis show some interesting results. First, we find that income dissimilarity, although not significant, has a positive coefficient. Just like income similarity, the size of the economies, India’s or the partner country’s, also does not influence IIT. The only exception to these is the group MTM Process. Another result that is contrary to theoretical predictions is the coefficient of the distance variable. The distance coefficient is consistently positive and significant for all groups. The impact of India’s FTAs on IIT reveals mixed results. While the coefficient is significant for 6 out of the ten groups, the impact is harmful to two of them, MTM Process and HTM E&E. On coming to the impact of the partner’s country RCA on IIT, and we find that in the cases where the coefficient is significant, it is mainly negative. On the other hand, India’s RCA is significant for most groups, and it is positive for all of them except RBM other and LTM textiles.

II Discussion

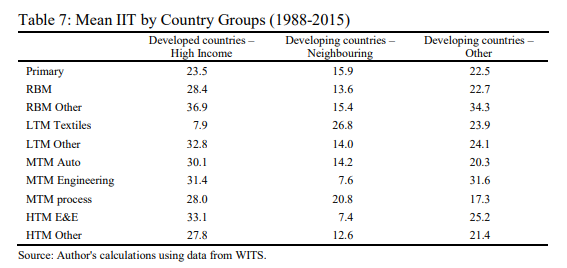

Although the coefficient of the difference in income is not significant, the results show that India’s IIT is higher with countries whose income (and thus demand patterns) are different. This result is in line with the results of Veeramani (2002) and Srivastava and Medury (2011). These studies have shown that India has higher IIT with countries that have higher income. If we calculate the mean IIT for developed and developing countries in our sample, we find that India’s IIT is consistently higher with the high-income countries for all groups other than

textiles. Table 7 shows that India’s IIT is much lower with its neighbouring developing countries compared to other developing and developing countries.

This indicates that India’s IIT leans more towards vertical IIT than horizontal. This is because it is generally assumed that countries with similar incomes have similar technological capacities and demand patterns. Thus, their trade is more horizontal (trade in similar but differentiated products). On the other hand, higher- income countries are more technologically advanced with different demand patterns. Thus, the trade with these countries would be more vertical, i.e., trade in the same product group but products at different production stages. The effect is the highest and significant only for one group, MTM Process, indicating that India is the supplier of parts and components to high-income economies in the MTM category.

The coefficient of the distance variable further lends support to the vertical IIT hypothesis. The distance variable is consistently positive and significant across all product categories, except MTM-Process. On the one hand, the countries close to India included in the sample (Nepal, Bangladesh and China) fall in the same income category, whereas the countries that lie further away are higher-income economies. However, the marginal effect of changes in the distance is small. The insignificant coefficients of the GDP variables indicate that the countries’ size (India and Partner) has no impact on IIT.

The size of the Indian economy has a positive effect on IIT for all product groups other than HTM-other. Thus, as India’s economy grows, we can expect the IIT to increase. However, this variable is insignificant for all groups except MTM- Process. On the other hand, the size of the partner country’s economy is consistently negative (the only exception being HTM E&E). The negative coefficient implies that as India’s trade partners grow and develop, India will not be able to keep up with its production capabilities which will reduce IIT. However,

even in this case, the coefficients are small and insignificant. MTM Process is the only exception, where the coefficient and the marginal effect are large.

When we try to determine the impact that competitiveness has on IIT between India and its partner countries, we find that the coefficient of India’s RCA is significant for eight out of the ten categories. Moreover, of the eight categories, it is positive for all except RBM-Other and LTM-textiles. Thus, we find that an increase in India’s comparative advantage increases its IIT. The positive coefficient of India’s RCA shows that Indian trade is efficiency-enhancing. The marginal effect of RCA is, in fact, highest in medium and high technology manufactures, indicating that India has the potential to increase its skill and efficiency levels in these products and benefit from added IIT. There is also potential for developing new skills. The two products for which RCA is negative (RBM-Other and LTM- Textiles) fall on the lower end of the skill spectrum and are largely labour- intensive. Moreover, the marginal effect of an increase in RCA is also smaller for them. The negative coefficient thus hints at a lack of labour in the high-income economies. Thus, these results suggest that India should focus on increasing its RCA in higher technology commodities.

Coming to the impact of the partner countries’ comparative advantage on IIT, we find that it is small and insignificant in most cases. However, out of the four groups for which it is significant, it is negative for three out of four of them (only exception – MTM Process). The result indicates that an increase in the comparative advantage of partner countries reduces their IIT with India, implying that India lacks either the technological capacity or the capacity to acquire technological know-how to compete with its partner countries. However, the marginal effects are quite small.

Lastly, we look at the impact of India’s FTA on IIT. The coefficients for FTA are significant for 6 out of the ten income categories. However, it is negative for 2 out of the 6 categories – MTM Process and HTM E&E. This negative coefficient implies that the agreements signed by India have not increased IIT in these categories but have instead had a trade diverting effect. However, for all other categories, FTA has been beneficial as IIT is welfare increasing (exploits economies of scale and allows for increased variety in consumption). Thus, contrary to the argument that India’s FTAs have not been beneficial as they have resulted in an increased trade deficit, we do find that the signing of FTAs has been welfare enhancing.

What is Happening with MTM Process?

Having discussed all our variables, we would like to focus on one product group that has consistently emerged as an exception in our discussion, MTM Process. This category is primarily made up of chemicals (paints, pigments, perfumes, soaps) and plastic products (tubes, plates, sheets). It also includes a few other products such as railway vehicles, trailers, and steel pipes and tubes.

Our results indicate that India and its partner countries’ RCAs have a positive effect on IIT. Thus, an increase in efficiency by either country (India or partner) increases IIT in this category. When we look at India’s RCA in the MTM process, we see that India does not have a comparative advantage in this category. Nevertheless, the RCA values have gradually been increasing. The value of RCA was 0.4 in 1988 and has increased to 0.8, even reaching a value of 1 in some years. Thus, India has potential in this sector, and an improvement in efficiency will bring about added benefits in increasing IIT.

Next, we see that an increase in the size of the partner country reduces IIT while an increase in India’s size increases IIT. The significant marginal effects of the two variables indicate that the group is susceptible to changes in the sizes of the economies. We believe that this trend is there because the share of this sector in India is minimal. If we look at the share of plastics and rubber in manufacturing output, we find that the share has hovered around 15-18 per cent since 1988. However, the sector’s share (only SITC 5-8)2 in exports is minimal. In 1988, it accounted for only 3 per cent of India’s exports, and it grew to approximately 7 per cent by 2015.

On the other hand, the share of imports was high initially, hovering between 9-11 per cent between 1988 and 1991. Although it came down to five per cent in the early 2000s, it has increased to approximately eight per cent in recent years. Thus, as partner economies grow, India’s sector becomes even smaller relatively. On the other hand, as India and its sector grow, the size of the sector becomes more comparable to other countries. This story is further corroborated by the sign and the marginal effect of the similarity variable, which is positive and large. As the economies become similar and more comparable, the IIT is likely to increase between the economies.

The relatively small size of the sector also explains why the results indicate that the group is susceptible to trade diversion.

Therefore, an analysis of this category reveals that this sector has potential for higher IIT and gains from it if India can enhance its efficiency and increase its size.

II Conclusion

The paper sought to examine India’s IIT with its top 15 partner countries. For this purpose, the products from SITC Rev. 3 groups 5 to 8 were divided into ten categories based on their technological content. The analysis of India’s IIT in these categories showed that although IIT has increased in recent years and is the dominant form of trade with the world, India’s trade with its top 15 partners still largely falls under the category of inter-industry trade. India has the highest IIT in Resource-based manufactures, whereas IIT is the lowest in low technology- intensive textiles.

The empirical analysis conducted to determine the factors of IIT revealed that India’s RCA plays a significant role in increasing IIT for technological categories. We also find that India’s FTAs have been IIT enhancing. Thus, in contrast to the

notion that India has not benefitted from its FTAs, we find that IIT has increased with FTA partners. Thus, there are benefits to be derived from trade agreements. Moreover, contrary to theory and previous empirical findings in this area, we find that India’s IIT increases with distance. However, this result, we believe, indicates the dominance of India’s IIT with developed countries that are located far away and lower IIT with its developing neighbours.

Lastly, a particular focus on medium technology process-based manufactures reveals the existence of potential to be exploited in this category. An increase in efficiency and overall growth in the Indian economy can benefit this sector. However, the sector is susceptible to trade diversion from FTAs due to its relatively small size.

Thus, the paper provides some insightful results about the nature of India’s IIT and the factors that play an essential role in driving it. This paper is a vital addition to the literature on IIT in India, mainly because of its innovative way of categorising products. However, it is essential to remember that while the classification of goods into technological categories using the Lall classification is widely accepted and used, it is subjective. Also, the nature of goods constantly changes due to technological changes. Hence, several products may be wrongly categorised.

An important point to note here is that the study does not consider the role of multinationals or FDI in IIT. In recent years, MNCs and FDI have been instrumental in driving the extent of IIT between countries. As more and more MNCs outsource or offshore their production processes, there is an increase in IIT due to trade in parts and unfinished goods. This IIT is, more often than not, vertical. Despite the importance of MNCs and FDI, these factors have been ignored since they use different indices to measure the share of IIT that is vertical and horizontal. Such distinction between the two types would give us more insight into the factors determining IIT and lead to better policy recommendations.

Endnotes

1. Crude oil forms a large part of these imports.

2. The group has 28 products at the 3rd digit in total of which 26 are from SITC groups 5-8. The two products thus excluded from our study in this group are products 266 (Synthetic fibres suitable for spinning) and 267 (Other man-made fibres suitable for spinning).

References

Aditya, A. and I. Gupta (2019), Intra-industry Trade of India: Is It Horizontal or Vertical? Economic and Political Weekly, 54(25): 29-38.

Aggarwal, S. and D. Chakraborty (2019), Which Factors Influence India’s Intra-Industry Trade? Empirical Findings for Select Sectors, Global Business Review, 23(3): 729-755, https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150919868343

Bagchi, S. (2018), Is Intra-Industry Trade Gainful? Evidence from Manufacturing Industries of India, India Studies in Business and Economics, In N.S. Siddharthan and K. Narayanan (Ed.), Globalisation of Technology, pp. 229-251, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5424-2_10

Balassa, Bela (1963), An Empirical Demonstration of Classical Comparative Cost Theory, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 45(3): 231-238.

———- (1966), Tariff Reductions and Trade in Manufactures among Industrial Countries, American Economic Review, (56): 466-473.

———- (1979), Intra-Industry Trade and the Integration of the Developing Countries in the World Economy, In Herbert Giersch (Ed.), On the Economics of Intra-Industry Trade: Symposium 1978, pp. 245-270, Mohr.

Bhadouria, P.S. and N. Verma (2012), Intra-Industry Trade in Textile Industry: The Case of India, International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 4(1/2): 199-212, doi:10.1504/ ijebr.2012.044253

Burange, L.G. and S.J. Chaddha (2008), India’s Revealed Comparative Advantage in Merchandise Trade, Artha Vijnana: Journal of The Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, 50(4): 332- 363, doi:10.21648/arthavij/2008/v50/i4/115413

Das, R.U. and J. Dubey (2014), Mechanics of Intra-Industry Trade and FTA Implications for India in RCEP, SSRN Electronic Journal, doi:10.2139/ssrn.2430185

Globerman, Steven and James Dean (1992), A Puzzle about Intra-Industry Trade: A Reply, Review of World Economics (Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv), 128(4): 747-748.

Grubel, H.G. (1967), Intra-Industry Specialisation and the Pattern of Trade, Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 33(3): 374-388.

Grubel, H.G. and P.J. Llyod (1975), Intra-Industry Trade, London: The Macmillian Press Ltd. Helpman, E. (1981), International Trade in the Presence of Production Differentiation, Economies of

Scale and Monopolistic Competition, Journal of International Economics, 11(3): 305-340.

Helpman, E. (1987), Imperfect Competition and International Trade: Evidence from Fourteen Industrial Countries, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 1(1): 62-81.

Kojima, K. (1964), The Pattern of International Trade Among Advanced Countries, Hitotsubashi Journal of Economics, 5(1): 16-34.

Krugman, Paul (1979), Increasing Returns, Monopolistic Competition, and International Trade,

Journal of International Economics, 9(4): 469-479.

Krugman, Paul (1981), Intra-Industry Specialisation and the Gains from Trade, Journal of Political Economy, 89(5): 959-973.

Lall, Sanjaya (2000), The Technological Structure and Performance of Developing Country Manufactured Exports, 1985‐98, Oxford Development Studies, 28(3): 337-369.

Lancaster, K. (1980), Intra-Industry Trade under Perfect Monopolistic Competition, Journal of International Economics, 10(2): 151-176.

Leontief, W.W. (1936), Quantitative Input and Output Relations in the Economic Systems of the United States, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 18(3): 105-125. doi:10.2307/1927837

Linder, S.B. (1961), An Essay on Trade and Transformation. New York: John Wiley.

Lloyd, P.J. and H. Yi (2005), Frontiers of Research in Intra-Industry Trade, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Manrique, G. (1987), Intra-Industry Trade between Developed and Developing Countries: The United States and the NICs, The Journal of Developing Areas, 21(4): 481-494, Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4191595.

Papke, L.E. and J.M. Wooldridge (2008), Panel Data Methods for Fractional Response Variables with an Application to Test Pass Rates, Journal of Econometrics, 145(1-2): 121-133, doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2008.05.009

Srivastava, A. and Y. Medury (2011), An Overview of India’s Intra-Industry Trade, Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 7(1): 153-160, Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/097324701100700112.

Varma, P. and A. Ramakrishnan (2014), An Analysis of the Structure and the Determinants of Intra- Industry Trade in Agri-food Products: Case of India and Selected FTAs, Millennial Asia, 5(2): 179-196, doi:10.1177/0976399614541193

Veeramani, C. (2002), Intra-Industry Trade of India: Trends and Country-Specific Factors, Review of World Economics (Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv), 138(3): 509-533, 10.1007/BF02707952.

———- (2007), Industry-Specific Determinants of Intra-Industry Trade in India, Indian Economic Review, 42(2): 211-229, new series, Retrieved on March 14, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org

/stable/29793889

Verdoorn, P.J. (1960), The Intra-Bloc Trade of Benelux, In EAG Economic Consequences of the Size of Nations, by J. Robinson, London: Macmillan.