Migration-Led Development in Kerala: Looking Beyond Growth and Remittances

June 2023 | K. Jafar

I Introduction

The development experience of Kerala has attracted wider attention for its unique patterns. State’s active involvement in the process of development was supported by social and political conditions. The progress in social and human development areas helped Kerala generate economic growth later and maintain its achievements in human development indicators. Studies identify different phases of Kerala’s development; it passed through a low growth phase in the 1970s and entered a high growth phase by the late 1980s. By the 1970s, Kerala achieved remarkable progress in human and social development areas, but the commodity-producing sectors remained stagnant (CDS-UN, 1975). This lop-sided development pattern (high social development with low economic growth) became popular as the ‘Kerala model of development’. Over time, there have been critiques and questions regarding this model. Some have questioned the existence of such a model1 and shared concerns about its replicability and sustainability (Parayil 1996, Tharakan 2006, Véron 2001). Some others have highlighted the exclusive nature of this model and identified SCs, STs, and fisher folk in the margins or outliers of the Kerala model of development (Deshpande 2000, Kurien 1995, Raman 2010,

Author thank Prof. Sujata Patel for her support and detailed comments and suggestions while conceiving and revising multiple drafts of this manuscript. The detailed review report from the anonymous reviewer also helped in revising the draft. None of them are responsible for any error remains.

Sivanandan 1979, Shyjan and Sunitha 2009). With new forms of marginalisation, these groups continue in the margin. The marginalised groups are excluded from productive resources, even with popular and radical policies like land reforms. The transformation of politics from public action mode to liberal mode can be linked to widening economic inequalities and abjection2 of these vulnerable groups (Devika 2010, 2013).

Discussions on Kerala’s migration-led development process often limit their focus on the growth dimensions. A large number of studies focus on the economic mobility and positive aspects of migration and remittances, while a limited number of studies focus on other dimensions (Gulati 1993, Kurien 2002, Osella and Osella 2000). The paper attempts to see the interface between scholarships from economists, sociologists, and anthropologists on Kerala’s experience with migration-led development. Along with the secondary sources, it uses the primary evidence drawn from micro-level studies and fieldwork conducted in Malappuram district of Kerala. The district’s dominance in Gulf migration and Muslim majority in the district’s population set an interesting context to explore the complex process of mobility and stratification in Kerala.

The paper reviews the broad patterns of the migration-led development process in Kerala. Withdrawal of the state from social sector spending and steady growth of private players with remittance inflow in the new growth phase may challenge state’s image as a champion of public action and social justice. The section also highlights the importance of remittances beyond boosting household consumption and the distinct role of Gulf migration. The impact of migration cannot be reduced to household remittances; It then discusses the role of migration in shaping gender relations and the way multiple identities such as region, religion and migration intersect in the context of Gulf migration in Kerala. The following section focus on the experience of Malappuram district in Kerala to show how different regions and groups follow the larger patterns. It focuses on the exclusion of marginalised groups from the process of migration-led development and the experience of Muslim Gulfwives to show how culture, religion, family and migration status influence gender relations in complex ways. The last section summarises the discussion and concludes the paper.

II Methodology

The first part of the paper uses secondary evidence to map the broad pattern of Kerala’s migration-led development process. It identifies some key areas that are missing from the mainstream discussions and explores the possibilities of connecting them. The sociological approach shows how migration affects gender relations and the intersection of gender with other identities such as religion, region (ethnicity), and other factors. The later part of the paper uses the primary evidence collected through micro studies conducted in Malappuram district and explores how mobility and stratification work in a given context. This includes three household surveys focusing on specific issues related to the Malappuram

district’s experience with migration-led development. The first survey was conducted in 2010-2011 in the context of Panchayat election, the first election after revising the reservation for women to 50 per cent in all three tiers of local governance in Kerala. The survey covers 196 candidates contested to three-gram panchayats representing the coastal, midland, and highland regions of the Malappuram district.3 The second survey was conducted during 2011-2012 period that covered 752 households from the same gram panchayats. The study focused on the process of human development among migrant and non-migrant households.4 The third survey was conducted in 2015-2016 period that covered 360 households from the same regions (different gram panchayats) and focused on the impact of migration on formal and informal financial arrangements.5

III Migration and Development in Kerala: Emerging Trends

Studies have identified different phases of growth which Kerala experienced in recent decades. One can connect them with the radical policies initiated by the state. For several years, it prioritised the social sector, even at the cost of economic growth. It created a rich human capital base, but the state economy could not absorb the educated labour force according to their preferences. This led to a high unemployment rate among the educated youth and a shortage of labour in traditional agriculture and allied jobs (Mathew 1999, Nair 1999). The situation changed in the 1970s when the post-oil boom in West Asian countries created new demand for foreign workers and triggered large-scale emigration of Malayalee workers to Gulf countries (Nambiar 1995, Prakash 1998, Rajan and Kumar 2010, 2011). The inflow of remittances generated by Malayalee migrants in Wet Asia fueled the state economy and led Kerala to a high growth phase by the end of the 1980s. This turnaround in growth was later identified as ‘virtuous growth’ (CDS, 2005). The strategies followed in the earlier phase, i.e., investment in human capital and progress in human development, generated this ‘virtuous growth’ in the state (Chakraborty 2005, Kannan 2005). This has created new discussions on the relationship between economic growth and human development and possibilities of human capital and human development path to achieve economic growth.6

The process of human development generating economic growth continues in the new growth phase. Its earlier achievements in human development, especially education and demographic transition, helped the state improve the per capita income and continue remittance-led growth along with high human development for several years (Kannan 2022). At the same time, the nature of new growth phases has changed in specific ways. A closer look into strategies followed in two growth phases indicates a gradual withdrawal of public investment from mass education. For several years, the share of the social sector in Kerala’s total expenditure remained high, and education absorbed a significant share of the social sector expenditure (Oommen 2010: 73). The new growth phase experienced a steady decline in real social expenditure; share of education in total government expenditure declined from 29.28 per cent in 1982-1983 to 17.97 per cent in 2005-

2006 (Oommen 2008). The deficit and burden on the state’s finances caused by high social sector expenditure also limit its capacity to continue its earlier strategy of prioritising the social sector (George 1993).

State’s withdrawal from education and greater involvement of private players and remittances set new focus and priorities. This has adverse implications for educational development in the state. Many students from marginalised groups are less likely to access private schooling; their parents cannot afford to pay the fees (Dilip 2011, Valatheeswaran and Khan 2018). In the case of higher education, withdrawal of public spending and change in the focus adversely affect students from disadvantaged backgrounds. This has reduced access in the Malabar region (with nearly 41 per cent of the total population in Kerala) and for many students from SC, ST and the backward communities, particularly the Muslims (Nasiya 2022). Due to the increase in private costs, student-financed institutions, non- financial entry barriers, and inadequate attention to the problems of disadvantaged groups, Kerala’s educational system is becoming more exclusive (Kumar, and George 2009). The new growth phase, with the active participation of private players in the social sector and growth of remittances, reports steady growth of inequality in the state. Studies have reported sharp differences in household consumption expenditure patterns, especially between migrant and non-migrant households (Aravindan and Menon 2010, Oommen 2014, Sreeraj and Vakulabharanam 2015, Subrahmanyan and Prasad 2008, Jafar 2018).

Role of Household Remittances

The economic dimension of remittances in terms of boosting household expenditure and the domestic economy has been widely discussed. Through diasporas and migrant collectives, they finance a wide range of activities. During the election and major programmes, political parties mobilise resources from party members and well-wishers. The state government also recognises the potential of overseas Malayalees and diasporas in generating financial support and appealed during crises like megafloods and landslides of 2018 and the Covid-19 Pandemic and succeeded in attracting their financial support in the form of local investment, philanthropic support and other means. Similarly, informal collectives, activists, and community leaders also use their connections to generate financial support for migrants for their voluntary activities and charity (Osella 2018). The reverse flow of remittances in terms of diversion from the traditional channels of consumption and investments or money sent to the destinations for helping the migrants (in business or personal crisis), is another area missing from these discussions, and social remittances7 are the other two areas left in these discussions.

Gulf-migration: A Different Phase of Migration from Kerala

Kerala has a long history of migration; it had a negative net migration until 1947 (Rajan and Kumar 2010). Scholars have identified different phases of international

migration from India.8 An early account from the middle of the 19th century indicates that Malabar region had recruitment centres sending indentured labour and migration of Cherumas (scheduled caste) as a way to escape from the exploitation of landlords’ (Joseph 1988: 40). Since independence, Kerala experienced permanent migration of skilled and professional workers to countries like USA, Canada, UK, and Australia, and temporary migration of unskilled and semi-skilled workers to the Gulf or West Asia (Rajan and Kumar 2010: 10-18). While skilled migrants from India continue concentrating in Europe and America, West Asia remains the destination for unskilled migrants from India (Khadria 2009, 2011). To some extent, the early generation of unskilled manual labourers is now replaced with skilled professionals. Compared to the large-scale migration to the Gulf countries experienced across the state, high-skilled and professional migration is limited in its scale. Keralites migrate to other countries and states of India, but their large-scale migration to the Gulf countries is unique in terms of its scale, nature, and impact on the local economy and society. Compared to skilled migration to Europe, the USA, and other megacities within the country, the participation in Gulf migration is wider and inclusive. Low-skilled Gulf migrants, often from coming poor economic backgrounds, send a sizable proportion of their income as remittances. It has contributed more towards reducing poverty and unemployment in the state.

Plight of Inter-State/Domestic Migrants in Kerala

Kerala also attracts a large number of inter-state migrants. Out-migration of workers, aversion of educated workforce towards blue-collar jobs, the higher wage rate for casual work, preference of employers in Kerala for migrant labourers in Kerala and unemployment and crisis in the rural and farming sector, indebtedness, the positive role of the social network of migrants and other factors contribute to increased inflow of inter-state migrants to Kerala. One estimate from 2013 suggests that Kerala hosts approximately 2.5 million (equivalent to around 20 per cent of Kerala’s workforce) domestic migrant labourers in different sectors (Narayana, Venkiteswaran and Joseph 2013). The long-term trend indicates that until the 1990s, Kerala attracted more migrant workers from neighbouring states like Tamil Nadu while it attracted more long-distance migrant workers from-1990s (Peter and Narendran 2017). Compared to local workers, migrant workers are more vulnerable; they face challenges in accessing work, better wages, and living conditions. They face constant conflicts and contestations and stay under the state’s and residents’ surveillance (Prasad-Aleyamma 2017). The state introduced some targeted and innovative interventions for migrant workers including during crises like floods and covid-19 pandemic (Peter, Sanghvi, and Narendran 2020). However, the plight of inter-state migrants in the state, while compared with the local workers, remains a concern.

Migration and Gender Relations

With its remarkable achievements in some areas of human and social development, Kerala’s experience shows how higher literacy, education, wider access to public health, favourable sex ratio, and demographic transition influence gender relations. Women played a critical role in making the Kerala model and realising some of its achievements, like family planning (Devika 2002, Jeffrey 2001). At the same time, the promise of higher literacy and female education did not improve women’s role in decision-making within a household, control over resources, mobility, political freedom, participation in paid work, and public space (Gardner 2011, Gulati 1993, Kodoth and Eapen 2005, Mukhopadhyay 2007, Scaria 2014). Kerala is an interesting case to see how migration and access to remittance affect these patterns further. Various rounds of the Kerala Migration Survey (KMS) indicate that nearly one in every ten married women in the state is a Gulf wife9 (Zachariah and Rajan 2012, Rajan and Zachariah 2018).

The relative absence of women in migration and the concentration of women migrants in specific jobs (like nursing and domestic duties) indicate limited participation of women in the migration (Neetha 2011, Percot and Nair 2011). As per recent estimates, nurses account for 45 per cent of female migrants from Kerala in 2018 (Rajan and Zachariah 2019). It is interesting to note that migration and new opportunities may change the existing gender relations and gender norms related to work in multiple ways. For instance, the nursing job was traditionally considered low status, and men hardly engaged in it. However, the community’s perspective and gender norms related to the nursing job changed when migration opened new opportunities (Kurien 2014). Male migration affects women and families left behind in multiple ways. Women from migrant families play multiple roles; they face new challenges and opportunities in the absence of their men (Desai and Banerji 2008, Gallego, Rajan and Bedi 2020, Gardner 2011, Gardner and Osella 2003, Gulati 1993, Zachariah and Rajan 2012). In several contexts, migration affects women’s access to resources and controls over them and participation in household decision-making, etc. (Fakir and Abedin 2021, Lamichhane, Puri, Tamang and Dulal 2011, Sinha, Jha and Negi 2012).

The experience of ‘Gulf wives’ offers many insights into how migration influences gender relations and women’s engagement with public space reflects on various institutional practices, including social, political, economic, and cultural factors that function locally (Zachariah, Mathew and Rajan 2003, Zachariah and Rajan 2009, 2012). One of the recent studies compared the experience of Gulf wives and women from non-migrant households in the northern, central and southern regions of Kerala. The results indicate that the husband’s migration improves the Gulf wife’s participation in decision-making in the household and improves her control over the resources and mobility. Compared to married women from non-migrant households, Gulf wives improved their agency, freedom and access to resources (Sajida 2020). At the same time, male migration adversely affects Gulf wives’ participation in paid work; most of them remain as home-

makers engaged in unpaid care work at home, and this may be seen in the light of falling female labour force participation in the state (Abraham 2013, Khan and Valatheeswaran 2020, Menon and Bhagat 2021).

Women’s participation and nature of engagement within the house and various spaces outside and can be influenced by religion/culture, norms, migration status, and their intersections. In this process, a particular identity may dominate over others and influence the outcome or become weak in a given context. Different institutions and their practices produce and reproduce crosscutting identities and their impact on women from different communities (Kosambi 1995). Instead of a single marker of inequality, the intersectionality approach allows one to see the intertwined nature of identities and their role in creating the position of privilege and disadvantage and influencing the situation of individuals and groups (Brewer, Conrad and King 2002, Severs, Celis and Erzeel 2016).

Gulf Migration and Malabar Muslims

Besides economic factors, migration of Malayalees can be connected with social considerations, including family, community, cosmopolitan identity and the likely positive impact (Tsai 2016). The state’s early social reformation and development have played a critical role towards the progress of Muslims in Kerala in different areas. The active participation of Malabar Muslims10 in migration, particularly in Gulf migration, can be looked at from multiple perspectives. This should not be limited to a generalised cultural imagining around West Asian Gulf. Several factors make the migration experience distinct in each state; hence, migrants’ preferences vary between these states (Osella and Osella 2008). Various rounds of KMS indicate that Muslims dominate in Gulf migration. In 2018, nearly 42 per cent of total emigrants from Kerala are Muslims. While 18 per cent of households in Kerala have at least one migrant, the corresponding share for Muslim households is 33 per cent. For various reasons, West Asian countries continue to be the favourite destinations (with 90 per cent of migrants) of Malyalee migrants over the years (Rajan and Zachariah 2019). Given the active participation of Malabar districts with a significant share of Muslim population, a closer look will provide more insights into the role of region and culture in the process of migration. The long tradition of ocean trade between Malabar Coast and Arab traders could have facilitated cultural exchanges and generated interests beyond the trade. This connection also could have contributed to large-scale Gulf migration in the Malabar region and helped Kerala Muslims succeed in the Gulf migration (Joseph 2001, Khan 2019).

The concentration of migrants from specific regions and groups may create migration chains or networks. For instance, migrants from Malappuram district were found concentrating in Saudi Arabia (Shibinu 2021). In the case of Saudi Arabia, a country that hosts the two holly masjids, other important marks of Islamic traditions, and rituals like Haj and Umrah, religious education plays an important role in accessing basic knowledge about the region, history, culture and

key practices to Muslims.11 As a result, many Muslims, including men and women who had never visited those countries, easily identify the locality and province where the migrant family member is located. Saudi Arabia has made special provisions for granting visas for religious pilgrims participating in Haj (scheduled on specific days every year) and Umrah (throughout the year) for a limited period. The accounts of the early migrants indicate that many of them used this provision; they explored job opportunities and extended their stay beyond the permitted period. Studies have referenced Mappila Muslim migrants using informal networks or illegally continuing their stay after expiring the visa granted (for a limited period) for religious pilgrimages (Khan 2019, Kurien 2014). Some stay longer and seek legal support to continue as migrant workers, while others get deported to their home country.

A comparative study on three ethnoreligious communities from Kerala, Mappila Muslims of northern Kerala, Ezhava Hindus of southern Kerala, and Syrian Christians of south-central Kerala, shows that different identities interact and influence their migration experiences.12 The community identities and ethnicities (Malabar region historically lags behind the other two regions in almost all indicators of development) 13 represent specific statuses. Their migration experience varies in almost all aspects, including migration, connection with the destination, nature of migration, education, skill-sets and nature of jobs, social- demographic characteristics of their families back in Kerala, and gender relations (Kurien, 2002). The perspective of the sociology of religion helps us understand the critical role of religion in migration. It shows ‘how religion can shape migration patterns by determining societal structures such as the social location of groups within society, which in turn influences the fundamental characteristics of groups and gives rise to differential state policies toward them’ (Kurien 2014: 534).

IV Kerala’s Migration Experience: Micro Evidences from Malappuram District

At the macro level, the process of education and migration-led development continues, but the nature of growth and implications change in specific ways. It is important to see how different regions and groups within the state follow the larger pattern and map their experience. Studies tend to aggregate Kerala’s migration experience into some common characteristics related to the economic conditions and key indicators of development. Many highlight the economic conditions in the origin and destinations, i.e., excess supply of educated workforce in origin and the demand for foreign workers in the destination, as the context for large-scale migration from Kerala to the Gulf countries. At the same time, migrant accounts are shaped by regional, cultural, and class identities, differences in education or professional qualifications, the nature of jobs, and other local factors. Some recent studies explore the way tradition and culture, food, fashion, ritual, lifestyle, business, articulation of religious and cultural identities, language, collective formation, and identities move between origins and destinations (Osella and Osella

2008, 2009).14 The remaining section focus on evidence collected through micro studies conducted in different parts of Malappuram district and attempts to revisit the larger discussion.

Malappuram, one of the Malabar districts, continues sending the largest number of emigrants and receiving the highest amount of household remittances in Kerala (Rajan and Zachariah 2019). According to the estimates of the Kerala Migration Survey 2018, migrant households from Malappuram district received

20.6 per cent of the total remittances Kerala received (of ₹30717 crores). Nearly

33.9 per cent of households in Malappuram districts receive remittances compared to 16.3 per cent in Kerala (Rajan and Zachariah 2019). However, the district holds a lower rank in terms of remittances estimated per migrant compared to districts that have more skilled and professional migrants. District’s earlier image as a backward district and Muslim majority in the total district population makes its experience interesting. It offers some critical insights into the exclusive nature of migration-led development and the intersection of gender with other identities.

Mobility in the Margins

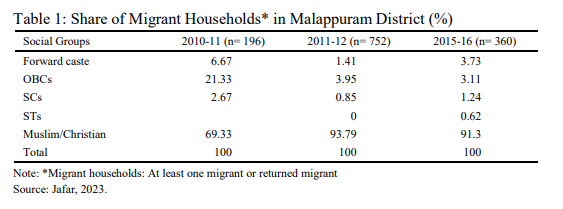

Migration and household remittances promoted upward social and economic mobility of migrant families and helped Kerala sustain its record human development with a growth rate. Within the state, regions and communities follow migration-led development differently. Primary surveys conducted in different regions of Malappuram district indicate very limited participation of Dalit

/Scheduled Caste households (SC) and Adivasis/Scheduled Tribes (ST) (Table 1). In the case of the first survey, their candidature in a competitive election indicates their relative status, better than others. In the case of the last survey, access to land helped many of the respondents to access the root of migration. However, the majority of households from these two marginalised groups do not have access to any form of capital and the possibility to participate in migration. There are many instances where migration does not lead to upward social or economic mobility. For many, unsuccessful migration and the cost of migration lead to vulnerability. Nearly half of the fishing households in the coastal villages have at least one member ever migrated. However, most of them are currently returned; many have returned after a short duration (due to poor earnings, the insecure nature of the job, accidents during fishing activity, etc.) and are living with a huge financial burden (Jafar 2018).

For those who managed to migrate from these marginalised communities, possessing land and assets helped some of them mobilise the money required for migration. In some cases, they received support from another affluent migrant family, often with long years of association of working for such families. However, most of these households need access to such physical or social capital15 and social networks; migration does not emerge as an effective strategy to overcome the vulnerability. The absence of these marginalised communities, identified as the ‘outlier’ of the so-called Kerala model of development, indicates

the exclusive nature of the migration-led model and limited mobility in the margins. Considering the positive contribution of migration in reducing poverty in the state (Zachariah, et. al. 2003: 63), promoting safe and successful migration among these communities is a priority. For various reasons, these groups continue on the margins of development; popular policies and flagship programmes like land reforms, decentralisation, Kudumbashree mission, MGNREGS, etc., have limited impact on their lives.

The Experience of Muslim Gulf-Wives

One of the earlier estimates indicates that Malappuram district accounts for 25.8 per cent of all Gulf-wives in Kerala where ‘the husband of one in every four married women is living abroad’ (against 1 in every 10 for Kerala). Muslim Gulf wives comprise more than half of the total Gulf wives in the state (Zachariah and Rajan 2012: 194, Rajan and Zachariah 2018). The experience of Muslim Gulf wives offers some interesting insights into how multiple identities like gender, migration status and religion intersect and influence gender relations in the state. Muslim Gulf wives independently engage with public spaces like banks, local government offices, children’s educational institutions, and hospitals but keep away from local politics, self-help groups, and casual wage work, including MGNREGA (Jafar 2018). The first set of places is often seen as neutral or need- based engagements (especially in the absence of migrant husbands/male family members). In contrast, the latter is seen as optional and monitored differently.

The evidence collected during the 2010 Panchayat election in Kerala shows how migration status, religion, and family influence women’s participation in politics and competitive elections. The absence of husbands discourages Gulf wives from participating in local politics and competitive elections. Only two gulf- wives (out of 196 total candidates) contested from three-gram panchayats. Both candidates relied on their families to manage the election process, campaign, documentation and other formalities. Interestingly, one of the candidates reported that her husband came and managed the entire election process; she did not know the nomination details, election campaign, expenditure, etc. After the election, her husband returned to Gulf and came again shortly to submit the documents on

election expenditure to the concerned office. For the second candidate, the husband’s family provided all the support required in his absence (Jafar 2013). Overall, we find that migration status does not directly contribute to candidature, but remittances continue financing political parties and their election activities.

In many contexts, cultural and religious factors discourage Muslim women from contesting in competitive elections. Being the first election after implementing the 50 per cent reservation for women, political parties had to identify potential women candidates, often without prior experience in local politics and leadership. By considering the challenges in identifying Muslim women candidates, especially in Muslim-dominated places, community leaders and authorities representing traditional and conservative Muslim organisations became flexible. They allowed Muslim women to contest in the 2010 local election. However, some leaders changed this position and discouraged political parties from fielding Muslim women candidates in the recent elections.16 The concentration of voters supporting a specific party also may lead to situations where the opposite parties find it difficult to contest the election. When such seats become reserved for women and SC or ST, it leads to complexities in identifying the candidates. In one of the coastal villages with a Muslim majority and supporters of the Indian Union Muslim League, the local party approached a young Muslim woman to represent them and contest in the election. She accepted to submit her nomination only after she consulted and got permission from the Imam (who leads the prayers and rituals) from the local Masjid (Jafar 2013). The political party considered her image as a traditional Muslim among the local Muslims for winning the election.

In another context, a local political leader approached one of his relatives and negotiated to make a young woman contest from the gram panchayat ward where he used to contest. For specific reasons, another young woman from the same family (a Gulf wife, younger sister-in-law of the primary candidate) was identified as the supporting candidate (a backup in case the main candidate’s nomination gets rejected on technical grounds). Both sisters submitted their nominations to the concerned office, and this was telecasted on a local TV channel, and the husband happened to see the same. As the Gulf wife could not get the support of her husband, she decided to withdraw her nomination at any cost. Only after she started fasting and refused to take any food did others agree to her demand to withdraw her nomination (Jafar 2013). These instances indicate that the family, often driven by culture/religion controls Muslim women’s engagement in local politics and discourage many potential young Muslim women from contesting in the election.

In many contexts, the popular understanding of Muslim women’s agency and subjectivity fails in conceiving agency within ‘irrational’ acts. For instance, Muslim women’s veil is primarily seen as a symbol of subordination or as a strong marker of resistance. The recent debate around the banning of Hijab in educational institutions in the southern state of Karnataka gives some insights into the limited choice available to Muslim girls; to choose between education or defend the

markers of cultural identity (Arafath and Arunima 2022). In such contexts, ‘intersectionality provides a critical lens to analyse articulations of power and subjectivity in different instances of social formations (economic, political, social and cultural), an intersectional approach to agency… and would turn its focus instead to specific contexts and articulated social formations from which different forms of agency and subject positions arise’ (Bilge 2010: 23). In some contexts, one particular identity may take ‘one away from other social identities and lend importance to social interactions (Mehrotra 2013).

II Concluding Remarks

The paper attempts to map Kerala’s experience with migration-led development beyond the growth story and popular narratives around the state’s role in promoting distribution and human development. The Kerala model of development and virtuous growth occupies an important place in the recent debates on Kerala’s development experience. While it is essential to map different phases of development and factors that link them, the discussion need not be limited to these aspects alone. The recent experience indicates that the education and migration- led development process continues, but the nature of this process changes as the state withdraws from financing social sectors. The active participation of private players with more involvement of remittances changes the priorities and makes Kerala’s development process more exclusive. The differential access to remittances contributed to the growing inequality in the state. Within the state, each group and region follow the larger model differently. The plight of inter-state migrants in Kerala and limited participation of households from marginalised communities in migration indicate the exclusive nature of migration-led development in Kerala. The varied experience of regions and groups challenges its earlier records in social development and public action, delivering social justice.

The discussion suggests that non-economic factors also influence the nature and pattern of migration and its impact on both origin and destinations. For instance, a closer look into Kerala’s success in Gulf migration and active participation of Muslims and Malabar region can explore multiple connections between the Persian Gulf and Malabar. It emphasises on mapping the distinct experience of migration and its varied impact, instead of generalised accounts. Migration and access to remittances influence gender relations in different ways. The intersection of multiple identities like gender, religion, caste, and migration status makes this complex. Studies report a sharp difference in how migration influences women’s status in different communities (Kurien 2002, 2014). The experience of Muslim women in Kerala shows that migration status positively influences the participation of Gulf wives in household decision-making, control over resources and mobility of women from migrant households but adversely affects their participation in paid work (Sajida 2020). The absence of husbands

discourages the Gulf wives from participating in local politics and competitive elections or makes them passive actors.

Besides the mainstream discussion followed in economics and development, the discussion explores the possibilities of sociological approaches, especially in mapping the relationships between migration and identities formed by gender and religion. With given challenges and opportunities, the experience of Muslim Gulf- wives in Malabar offers some insights into how migration, religion, and region are configuring gender relations. Access to remittances and multiple roles in the family empower them in certain areas while it does not help them in other areas like engaging in public spaces where family and religion become more active. In some contexts, their personal capabilities gained through education or financial independence may help them in overcoming such controls. The discussion maps some potential areas where the approaches and existing research can be extended.

Endnotes

1. Even if we do not call this as a model or dismiss the existence of a specific plan or strategy followed earlier, one need to recognize the fact that Kerala experienced a unique development pattern for many years. This could have evolved out of its social and political processes over the years.

2. ‘Abjection’ refers to the social process by which the normal, the possible, the dominant, the sensible and the mainstream are produced and supported by the creation of a domain of abnormality, impossibility, subservience and marginality’ (Devika 2013).

3. (Jafar 2013)

4. (Jafar 2018)

5. Jafar, K. (2017). ‘The Impact of Regional Diversity, Remittances, and Culture on Local Finance: A Study of Malappuram District, Kerala’. Report submitted to the ICSSR New Delhi and CSD, Hyderabad.

6. Kerala’s experience depicts the dynamic relationship between economic growth and human development two ways; where economic growth leads to human development or human development achievements contribute to economic growth.

7. In multiple forms including as donation/contribution made ‘in the form of religious buildings and practices, educational institutions, vocational aspirations and possibilities, celebrity NRI politicians, or hybridised cultural norms’ (Tsai 2021: 248)

8. One of the studies identifies four phases: first phase (1834–1910) with steady increase in the size of indentured labour emigration); second, (1910–15) with end of indentured labour emigration; third, (1921–30) with migration of workers to plantation areas of Ceylon, Burma and Malaysia) and fourth by 1938, with the end of kangani/maistry form of emigration and beginning of voluntary labour migration (Jain 2011). Another study identifies three phases namely, indentured labour migration (1834–1910), emigration under Kangani system (1910– 35) and free migration (1936–47) (Rajan and Kumar 2010: 2–10).

9. The term “Gulf wives” refers to married women whose husbands are, or have been migrants. They include women whose husbands were migrants at the time of the survey and whose husbands had returned after migration to the Persian Gulf countries (Zachariah, and Rajan 2001). Studies often consider ‘Gulf-wives’ as a subset of ‘women left behind’ (WLB). Since more than 95 per cent of the total married women left behind in our sample are Gulf-wives, the present study use ‘Gulf-wives’ as a common category which includes all women left behind. Compared to other women from migrant households, Gulf-wives face certain

challenges and opportunities more frequently and the same factor may justify this classification.

10. Malabar Muslims are often identified as Mappila/Moplah Muslims; they represent a distinct identity.

11. This can be considered as some kind of pre-departure orientation or information.

12. Author finds ethnic behaviour as ‘kaleidoscopic’, where ethnicity allows to realign and reformulating of social relationships in the disintegration and transformation of communities and maps the changes in their social structures.

13. Malabar initiated the social reformations and development of education and health very late and this difference in regional development continued for several years (Kabir 2002).

14. Literature and popular media especially films capture some of these changes in interesting way. They narrate the transformation of families through migration, image of the migrants and negotiations.

15. A network or institution can improve its members’ capacity to access limited resources or spaces. Social capital means “features of social organisation such as networks, norms and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” (Putnam 1995: 67).

16. During 2021 assembly election, Muslim leaders openly criticised Muslim League for fielding a woman candidate. A woman candidate contested from a constituency which traditionally elected Muslim League candidates but she could not win the election.

References

Abraham, V. (2013), Missing Labour or Consistent De-Feminisation’? Economic and Political Weekly, 48(31): 99-108.

Arafath, P.K.Y. and G. Arunima (2022), The Hijab: Islam, Women and the Politics of Clothing, New Delhi: Simon and Schuster India

Aravindan, K.P. and R.V.G. Menon (2010), A Snapshot of Kerala: Life and thought of the Malayalee People, Thrissur: Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad.

Bilge, S. (2010), Beyond Subordination vs. Resistance: An Intersectional Approach to the Agency of Veiled Muslim Women, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 31(1): 9-28.

Brewer, R.M., C.A. Conrad and M.C. King (2002), The Complexities and Potential of Theorising Gender, Caste, Race, and Class, Feminist Economics, 8(2): 3-17.

CDS (2005), Human Development Report 2005 Kerala (Centre for Development Studies [CDS], Prepared for Government of Kerala), Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala: State Planning Board.

CDS-UN (1975), Poverty, Unemployment and Development Policy: A Case Study of Selected Issues with Reference to Kerala, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, New York: United Nations.

Chakraborty, A. (2005), Kerala’s Changing Development Narratives, Economic and Political Weekly, 40(6): 541–547.

Desai, S. and M. Banerji (2008), Negotiated Identities: Male Migration and Left-behind Wives in India, Journal of Population Research, 25(3): 337-355.

Deshpande, A. (2000), Does Caste Still Define Disparity? A Look at Inequality in Kerala, India,

American Economic Review, 90(2): 322-325.

Devika, J. (2002), Family Planning as ‘Liberation’: The Ambiguities of ‘Emancipation from Biology’ in Keralam, Working Paper No. 335, Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies.

———- (2010), Egalitarian Developmentalism, Communist Mobilisation, and the Question of Caste in Kerala State, India, The Journal of Asian Studies, 69(3): 799-820.

———- (2013), Contemporary Dalit Assertions in Kerala: Governmental Categories vs Identity Politics? History and Sociology of South Asia, 7(1): 1-17.

Dilip, T.R. (2011), On the Diffusion of School Educational Attainment in Kerala State, Demography India, 40(1): 51–63.

Fakir, A. and N. Abedin (2021), Empowered by Absence: Does Male Out-Migration Empower Female Household Heads Left Behind? Journal of International Migration and Integration, 22(2): 503-527.

Gallego, J.R., S.I. Rajan and A.S. Bedi (2021), Impact of Male Migrants and their Return, on Women Left Behind: The Case of Kerala, India, In S.I. Rajan (Ed), India Migration Report 2020: Kerala Model of Migration Surveys, (pp. 97-111), Oxon: Routledge.

Gardner, A.M. (2011), Gulf Migration and the Family, Journal of Arabian Studies: Arabia, the Gulf, and the Red Sea, 1(1): 3-25.

Gardner, K. and F. Osella (2003), Migration, Modernity and Social Transformation in South Asia: An Overview, Contributions to Indian Sociology, 37(1 and 2): v-xxviii.

George, K.K. (1993), Limits to Kerala Model of Development: An Analysis of Fiscal Crisis and Its Implications, Monograph, Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies

Gulati, L. (1993), In the Absence of Their Men: The Impact of Male Migration on Women, New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Jafar, K. (2013), Reservation and Women’s Political Freedom: Candidates, Experience from Three Gram Panchayats in Kerala, India, Social Change, 43(1): 79–97.

———- (2018), Education, Migration and Human Development: Kerala Experience, Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

———- (2023), Mobility in the Margins: Experience of Migration and Development in Kerala, India, In A. Rahman, S. Babu M., Ansari P.A. (Eds), Indian Migration to the Gulf: Issues, Perspectives and Opportunities, Routledge India (Forthcoming).

Jain, C.P. (2011), British Colonialism and International Migration from India: Four Destinations, In,

S.I. Rajan and M. Percot (Eds.), Dynamics of Indian Migration: Historical and Current Perspectives (pp. 23–48), New Delhi: Routledge.

Jeffrey, R. (2001), Politics, Women and Well-being: How Kerala Became ‘A Model’, Oxford India Paperbacks. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Joseph, K.V. (1988), Migration and economic development of Kerala. Delhi: Mittal Publications.

———- (2001), Factors and Pattern of Migration: The Kerala Experience, Journal of Indian School of Political Economy, 13(1): 55–72.

Kabir, M. (2002), Growth of Service Sector in Kerala: A Comparative Study of Travancore and Malabar – 1901–1951, Ph.D. Thesis Submitted to CDS, Thiruvananthapuram, University of Kerala.

Kannan, K.P. (2005), Kerala’s Turnaround in Growth: Role of Social Development, Remittances and Reform, Economic and Political Weekly, 40(6): 548–554.

———- (2022), Kerala ‘Model’ of Development Revisited: A Sixty-Year Assessment of Successes and Failures, Working Paper 510, Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies.

Khadria, B. (2009), India-Migration Report 2009: Past, Present, and the Future Outlook. International Migration and Diaspora Studies Project, School of Social Sciences at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi: Cambridge University Press India Pvt. Ltd.

———- (2011), Bridging the Binaries of Skilled and Unskilled Migration from India, In, S.I. Rajan and M. Percot (Eds.), Dynamics of Indian Migration: Historical and Current Perspectives (pp. 251–285), New Delhi: Routledge.

Khan, A.T.A. (2019), Forced Migration of Muslims from Kerala to Gulf Countries, In S.I. Rajan, P. Saxena (Eds.) India’s Low-Skilled Migration to the Middle East: Policies, Politics and Challenges. (pp. 207-222), Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Khan, M.I. and C. Valatheeswaran (2020), International Remittances and Private Healthcare in Kerala, India, Migration Letters, 17(3): 445-460.

Kodoth, P. and M. Eapen (2005), Looking Beyond Gender Parity: Gender Inequities of Some Dimensions of Well-being in Kerala, Economic and Political Weekly, 40(30): 3278–3286.

Kosambi, M. (1995), An Uneasy Intersection: Gender, Ethnicity, and Crosscutting Identities in India,

Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society, 2(2): 181-194.

Kumar, N.A. and K.K. George (2009), Kerala’s Education System: From Inclusion to Exclusion?

Economic and Political Weekly, 55-61.

Kurien, J. (1995), The Kerala Model: Its Central Tendency and the Outliers, Social Scientist, 23(1/3): 70–90.

Kurien, P. (2014), Immigration, Community Formation, Political Incorporation, and Why Religion Matters: Migration and Settlement Patterns of the Indian Diaspora, Sociology of Religion, 75(4): 524-536.

Kurien, P.A. (2002), Kaleidoscopic Ethnicity: International Migration and the Reconstruction of Community Identities in India, Rutgers University Press.

Lamichhane, P., M. Puri, J. Tamang and B. Dulal (2011), Women’s Status and Violence against Young Married Women in Rural Nepal, BMC Women’s Health, 11(1): 1-9.

Mathew, E.T. (1999), Educated Unemployment in Kerala: Incidence, Causes and Policy Implications, In B.A. Prakash (Ed), Kerala’s Economic Development: Issues and Problems (pp. 94–115), New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Mehrotra, N. (2013), Disability, Gender and Caste Intersections in Indian Economy, In S.N. Barnartt,

B. Altman (Eds.), Disability and Intersecting Statuses (p. 295-324), Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Menon, R.R. and R.B. Bhagat (2021), Emigration and Its Effect on the Labour Force Participation of Women in the Left-behind Household, In S.I. Rajan (Ed), India Migration Report 2020: Kerala Model of Migration Surveys (pp. 162-176), Oxon: Routledge.

Mukhopadhyay, S. (2007), Understanding the Enigma of Women’s Status in Kerala: Does High Literacy Necessarily Translate into High Status? In, S. Mukhopadhyay (Ed.), The Enigma of the Kerala Woman: A Failed Promise of Literacy (pp. 3–31), New Delhi: Orient Longman.

Nair, M.K.S. (1999), Labour Shortage in a Labour Surplus Economy? A Study of the Rural Labour Market in Kerala, In M.A. Oommen (Ed.), Rethinking Development: Kerala’s Development Experience (pp. 247–268), Volume 2, Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

Nambiar, A.C.K. (1995), The Socio-Economic Conditions of Gulf Migrants, New Delhi: Commonwealth Publishers.

Narayana, D., C.S. Venkiteswaran and M.P. Joseph (2013), Domestic Migrant Labour in Kerala, Gulati Institute of Finance and taxation, report submitted to Labour and Rehabilitation Department, Government of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram.

Nasiya, V.K. (2022), Public Expenditure on Higher Education in Kerala: A Comparative Study of Pre and Post Liberalisation Period, Ph.D. Thesis, Government College Kodanchery, Kozhikode.

Neetha, N. (2011), Closely Woven: Domestic Work and International Migration of Women in India, In S.I. Rajan (Ed.), India Migration Report 2011: Migration, Identity and Conflict (pp. 219– 235), New Delhi: Routledge.

Oommen, M.A. (2008), Capabilities, Reform and the Kerala Model, Paper presented at the Annual Conference of Human Development and Capability Association, New Delhi, 10-13.

———- (2010), Freedom, Economic Reform and the Kerala ‘Model’, In K. R. Raman (Ed.), Development, Democracy and the State: Critiquing the Kerala Model of Development (pp. 71– 86), Oxon: Routledge.

———- (2014), Growth, Inequality and Well Being: Revisiting Fifty Years of Kerala’s Development Trajectory, Journal of South Asian Development, 9(2):173–205.

Osella, C. and F. Osella (2008), Nuancing the ‘Migrant Experience: Perspectives from Kerala, South India, In Transnational South Asians: The Making of a Neo-diaspora, (Eds.) S. Koshy and R. Radhakrishnan, (pp. 146-178), Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Osella, F. (2018), Charity and Philanthropy in South Asia: An Introduction, Modern Asian Studies, 52(1): 4-34.

Osella, F. and C. Osella (2009), Muslim Entrepreneurs in Public Life Between India and the Gulf: Making Good and Doing Good, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 15: S202- S221.

Osella, F., F. Caroline and C. Osella (2000), Social Mobility in Kerala: Modernity and Identity in Conflict, Pluto Press.

Parayil, G. (1996), The ‘Kerala Model’ of Development: Development and Sustainability in the Third World, Third World Quarterly, 17(5): 941–957.

Percot, P. and S. Nair (2011), Transcending Boundaries: Indian Nurses in International Migration, In S.I. Rajan and M. Percot (Eds.), Dynamics of Indian Migration: Historical and Current Perspectives (pp. 195–223), New Delhi: Routledge.

Peter, B. and V. Narendran (2017), God’s Own Workforce: Unravelling Labour Migration to Kerala, Centre for Migration and Inclusive Development.

Peter, B., S. Sanghvi and V. Narendran (2020), Inclusion of Interstate Migrant Workers in Kerala and Lessons for India, The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63(4): 1065-1086.

Platteau, J.P. (1997), Mutual Insurance as an Elusive Concept in Traditional Rural Communities,

The Journal of Development Studies, 33(6): 764–796.

Prakash, B.A. (1998), Gulf Migration and Its Economic Impact: The Kerala Experience, Economic and Political Weekly, 33(50): 3209–3213.

Prasad-Aleyamma, M. (2017), Cards and Carriers: Migration, Identification and Surveillance in Kerala, South India, Contemporary South Asia, 26(2): 191-205.

Putnam, R.D. (1995), Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital, Journal of Democracy, 6(1): 65-78.

Rajan S.I. and P. Kumar (2010), Historical Overview of International Migration, In S.I. Rajan (Ed.), India Migration Report 2010: Governance and Labour Migration (pp. 1–29), New Delhi: Routledge.

———- (2011), A Long Haul: Revisiting International Migration from India During the 19th and 20th Centuries, In D. Narayana and R. Mahadevan (Eds.), Shaping India: Economic Change in Historical Perspective (pp. 295–319), New Delhi: Routledge.

Rajan, S.I. and K.C. Zachariah (2018), Women Left Behind: Results from Kerala Migration Surveys, In S.I. Rajan and N. Neetha, (Eds.), Migration, Gender and Care Economy, Routledge India.

———- (2019), Emigration and Remittances: New Evidences from the Kerala Migration Survey 2018, Working Paper Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies.

Raman, K.R. (Ed.) (2010), Development, Democracy and the State: Critiquing the Kerala Model of Development, Oxon: Routledge.

Sajida, P. (2020), Impact of Male Migration on Capability Based Empowerment of Woman-A Study of Gulf Wives in Kerala, Ph.D. Thesis submitted to Cochin University of Science and Technology.

Scaria, S. (2014), A Dictated Space? Women and Their Well-being in a Kerala Village, Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 21(3): 421-449.

Severs, E., K. Celis and S. Erzeel (2016), Power, Privilege and Disadvantage: Intersectionality Theory and Political Representation, Politics, 36(4): 346–354.

Shibinu S. (2021), Socio-Economic Dynamics of Gulf Migration: A Panel Data Analysis, In S.I. Rajan (Ed), India Migration Report 2020: Kerala Model of Migration Surveys (pp. 120-135) Oxon: Routledge.

Shyjan, D. and A.S. Sunitha (2009), Changing Phases of Kerala’s Development Experience and the Exclusion of Scheduled Tribes: Towards an Explanation, Artha Vijnana, 51(4): 340–359.

Sinha, B., S. Jha and N.S. Negi (2012), Migration and Empowerment: The Experience of Women in Households in India Where Migration of a Husband Has Occurred, Journal of Gender Studies, 21(1): 61-76.

Sivanandan, P. (1979), Caste, Class and Economic Opportunity in Kerala: An Empirical Analysis,

Economic and Political Weekly, 14(7/8): 475–480.

Sreeraj, A.P. and V. Vakulabharanam (2016), High Growth and Rising Inequality in Kerala Since the 1980s, Oxford Development Studies, 44(4): 367–383.

Subrahmanian, K.K. and S. Prasad (2008), Rising Inequality with High Growth: Isn’t This Trend Worrisome? Analysis of Kerala Experience, Working paper, 401 Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies.

Tharakan, P.K.M. (2006), Kerala Model Revisited: New Problems, Fresh Challenges, Working Paper No. 15, Kochi: Centre for Socio-economic and Environmental Studies.

Tsai, K.S. (2016), Cosmopolitan Capitalism: Local State-Society Relations in China and India,

Journal of Asian Studies, 75(2): 335–361.

———- (2021), Social Remittances of Keralans in Neoliberal Circulation, In S.I. Rajan (Ed), India Migration Report 2020: Kerala Model of Migration Surveys (pp. 228-252), Oxon: Routledge. Valatheeswaran, C. and M.I. Khan (2018), International Remittances and Private Schooling:

Evidence from Kerala, India, International Migration, 56(1): 127-145.

Zachariah, K.C. and S.I. Rajan (2001), Gender Dimensions of Migration in Kerala: Macro and Micro Evidence, Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 16(3): 47-70.

———- (2009), Migration and Development: The Kerala Experience, Delhi: Daanish Books.

———- (2012), Kerala’s Gulf Connection, 1998-2011: Economic and Social Impact of Migration, New Delhi: Orient BlackSwan.

Zachariah, K.C., E.T. Mathew and S.I. Rajan (2003), Dynamics of Migration in Kerala: Dimensions, Differentials and Consequences, New Delhi: Orient Longman.