Taxonomic Evaluation of Health Infrastructure and COVID-19 Situation in India with Special Reference to Haryana State

September 2023 | Devender and Kirti

I Introduction

The vicious COVID-19 virus, also known as the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), rapidly spread all over the world and has created a situation of devastation for over one and a half years now (Shukla, Pradhan and Malik 2021). It has unanticipated effects on the global health system and created a difficult situation for the world economy (Arif and Sengupta 2021). It has also raised questions regarding health facilities in forward as well as backward countries. The virus was originally reported in Wuhan city (China) from an unidentified reservoir (suspected bats) in December, 2019 (Gauttam, Patel, Singh, Kaur, Chattu and Jakovljevic 2021, Riza, Erdogan, Agaoglu, Dineri, Cakirci, Senel, Okyay and Tasdogan 2020, Shukla, Pradhan and Malik 2021, Velavan and Meyer 2020). In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a global pandemic due to its rapid transmission from person to person and causing

Devender, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Government College for Girls, Pillukhera (Jind) 126113, Haryana, Email: devender2288@gmail.com

Kirti, Research Scholar, Department of Economics, Maharshi Dayanand University, Rohtak 124001, Haryana, Email: jk98027@gmail.com

many deaths globally (Kannan, Ali, Sheeza and Hemalatha 2020, Wang, Horby, Hayden and Gao 2020).

In India, the first case of COVID-19 was found in the Thrissur district of Kerala on January 30, 2020 (Sarkar, Khajanchi and Nieto 2020). The Government of India (GOI), as well as state governments had formulated a blueprint to tackle this pandemic; therefore various precautions were taken to overcome this difficult situation, which included nationwide lockdown and formation of containment zones. The Government of India (GOI) launched a smartphone based application namely Aarogya Setu which helped in tracking down infected persons, and also organised many awareness programs (Malani, Soman, Asher, Novosad, Imbet, Tandel, Agarwal, Alomar, Sarker, Shah, Shen, Gruber, Sachdeva, Kaiser and Bettencourt 2020, Banerjee, Alsan, Breza, Chandrasekhar, Chowdhury, Duflo, Goldsmith-Pinkham and Olken 2020, Gohel, Patel, Shah, Patel, Pandit and Raut 2021, Pandey, Prakash, Agur and Maruvada 2021), etc. Despite these precautions, confirmed cases steadily increased over time. Better health services are necessary to tackle the situation of COVID-19 and to improve overall quality of life, which is influenced by various factors such as demographic, environmental, hereditary, social and economic determinants, i.e., level of income, education, availability of basic amenities and health facilities (Varkey, Joy and Panda 2020). According to Kumar and Gupta (2012), the availability of health infrastructure (skilled workforce, public health organizations, information system, and research and development) in a region, is the most crucial factor that helps in improving the living standard of people.

However, the fact remained that the limited health infrastructure in the pandemic faced a stressful situation (Singh, Deedwania, K, Chowdhury and Khanna 2020). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 2021 weekly operational updates on COVID-19, as of 16th June 2021, a total number of 17,63,11,647 confirmed cases had been found, and 38,20,207 people died due to this pandemic. On the other hand, in India, the total number of confirmed cases was 2,96,99,589 (16.84 per cent of global cases) and reported 3,31,911 deaths (8.69 per cent of total global deaths) as of 16th June 2021. Herein, it is difficult to predict how much population is currently affected by this virus and how more people will be affected in the future (Petropoulos and Makridakis 2020). The Indian economy where a large proportion of the population lives in rural areas with widespread poverty, needs accessible and low-cost health facilities; therefore, the GOI consistently focused on providing more reliable and affordable health facilities for all. The GOI formulated its first National Health Policy (NHP) in 1983 to provide accessible healthcare services (Maulik, Patil, Khanna, Neogi, Sharma, Paul and Zodpey 2016), the second NHP in 2002 was also based on the previous policy to provide healthcare services through decentralisation as well as through the private sector (Singh 2008); furthermore, in 2017, the GOI introduced restructured NHP for universalisation of healthcare facilities with an approach Health in All (Gauttam, et. al. 2021). Therefore, the GOI increased its expenditure on health services; however, in 2017-2018, health expenditure as a percentage of

GDP was only 1.25 per cent and the per capita public expenditure on health was

₹1,657 (National Health Profile 2020). In 2020, there were 12,34,205 registered doctors (1 doctor per 1085 people) in State Medical Councils/Medical Councils and 15,54,022 beds (1 bed per 862 people) in government hospitals in India. As mentioned above, a large portion of the population in India lives in rural areas; therefore, the government provided a three-tier health facilities system for them (Rekha 2020), i.e., Community Health Centers (5,685), Primary Health Centers (20,069), and Sub Centers (1,52,794). Despite these steps, health facilities in India are not up to the mark, and the government is still facing a challenge to provide better health care (Dev and Sengupta 2020). Furthermore, due to the low availability of public health services, poor people cannot afford expensive healthcare facilities provided by private providers, as a result, they fall into the vicious circle of poverty (Varkey, et. al. 2020).

As a contrast to the above, Haryana is a state that has impressive growth rate and higher per capita income than its neighboring states (Devender and Kumar 2021). In 2020, its government hospitals had 14,517 doctors (1:1991), which was higher than national average; and 41,744 beds in hospitals as well as COVID-19 dedicated health centres (1:692), which was less than the national average. Moreover, health expenditure of the state government on health services was less than the national average, which is 0.68 percent of GDP and the per capita public expenditure on health was merely ₹1,168 in 2017-2018. As per media bulletin (issued by Press Information Bureau [2021], Government of India) on 16th June 2021 there were 2,652 confirmed positive cases per lakh of population, 1.19 per cent of fatality rate, and the weekly positivity rate had fallen to one per cent and

23.34 per cent population was covered through vaccination. Rapid testing/screening, identifying, quarantine and speedy vaccination are the optimum steps for prevention from this pandemic. The role of health infrastructure facilities is indispensable to control any pandemic; therefore, the main objective of this paper is to critically examine the performance of health infrastructure and COVID- 19 situation in India with special reference to Haryana state.

II Research Methodology

Choice of Indicators

The present study mainly deals with the availability of health infrastructure and the situation of the COVID-19 pandemic among 21 major Indian States/UTs (affected by the pandemic) and district level in Haryana.

Indicators Related to Health Infrastructure

In terms of health infrastructure, six indicators commonly available for all regions have been collected, i.e., number of hospitals per lakh of population (HI1), number

of beds per lakh of population (HI2), number of ICU beds per lakh of population (HI3), number of ventilators per lakh of population (HI4), number of testing laboratories (HI5), number of doctors per lakh of population (HI6). The data has been collected for the year 2020-2021 from various media bulletin and reports issued by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), GOI; National Health Profile, 2020; Health Department of Haryana; and Statistical Abstract of Haryana issued by Department of Economic and Statistical Analysis, Haryana (Various issues).

Indicators Related to COVID-19 Situation

The COVID-19 situation has been measured by five common indicators available among major Indian states as well as in districts of Haryana, i.e., number of confirmed cases per lakh of population (CI1), recovery rate (CI2), fatality rate (CI3), weekly positivity rate (CI4), and per cent population covered through vaccination (CI5). The data was collected with a cutoff date of 16th June 2021 from various media bulletins and reports issues by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), GOI; and Health Department of Haryana. For measuring indicators per lakh of population (some districts have population below one million, therefore, per lakh population has been used), the projected population of 2020 was estimated with the help of exponential growth from 2001 to 2011.

Choice of Methodology

There are several statistical methods available in the literature to construct a composite index but most of methods have their own limitations. Therefore, the present study used the ‘Wroclaw Taxonomic method’ developed by Florek, Lukaszewicz, Perkal, Steinhaus and Zubrzycki (1952) and further used by Ewusi (1976), Khan and Islam (1990), Narain, Rai and Shanti (1991), and Ohlan (2013). Steps of the method:

Let assume [Xij] had a data matrix for ith district and jth indicators. Here the selected indicators were expressed in different units of measurement; therefore, there was a need to transform [Xij] into the standardized score [Zij] as follows :

[𝑍ij] =

𝑥ij − 𝑥j

𝑠j

in which, 𝑥j = mean and 𝑠j = standard deviation.

𝑃ij = (𝑧ij − 𝑧oj)2

where Zoj is the optimal value of each indicator from [Zij]. The optimum value of the indicator would be the maximum value for all stimulant and the minimum value for all destimulant. The pattern of development has been given as:

n

𝐶i = (Σ 𝑃i ∕ (𝐶𝑉j)

J=1

where (CVj) = Coefficient of variation.

The composite index of health development is given by Di = Ci /C where C = 𝐶̅ + 3𝜎𝐶i, 𝐶̅= mean and 𝜎 = standard deviation.

where 0 <Di < 1 (If the value of Di is close to zero (0), then the particular

district has relatively better health infrastructure). This methodology was also used for the measurement of the situation of COVID-19 in Haryana, in which a low value of Di showed the particular region performed well and situated in a better situation in COVID-19.

Classification of Various Stages

A more meaningful classification of the districts based on their stages was carried out with the help of mean and standard deviation value as follows:

Better (IV) = Di≤ (𝑋¯- σ); Average (III) = 𝑋¯ >Di> (𝑋¯- σ); Poor (II) = 𝑋¯ <Di< (𝑋¯

- σ); Very Poor (I) = Di≥ (𝑋¯ + σ).

III State Level Analysis of Health Infrastructure and COVID-19 in India

The role of public expenditure is an important factor in providing affordable health services, especially in developing countries such as the Indian economy. In developed economies, the government spends much more on health services than in developing or less developed countries. According to the World Health Statistics Report (2018), expenditure on health services in the USA, Norway, and India’s neighbouring country Sri Lanka was 17.1, 10.5, and 3.9 per cent of GDP, respectively; whereas, in India, it was merely 3.6 per cent of GDP. However, the GOI has increased its expenditure on health serviced due to dire condition created by COVID-19 pandemic; according to budget estimates, the total health expenditure of GOI was 6501.2 billion ₹ in the financial year 2020-2021 (Kirti and Langyan 2020).

In India, the average number of hospitals per lakh population was five; nine states had a higher number of hospitals than the national average. Uttar Pradesh

was on top (17,103) whereas Jammu and Kashmir (157) had the lowest number of hospitals in India. However, among the number of hospitals per lakh population of a state, Karnataka had highest 17 hospitals, followed by Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. In terms of the number of hospital beds and ICU beds per lakh population, India’s average was 116 and 5 beds, respectively. Maharashtra had the highest 270 hospital beds per lakh population and Tamil Nadu had the highest 12 ICU beds per lakh population. Himachal Pradesh had the lowest number of hospital beds and Bihar had the lowest number of hospital beds per lakh population. In aggregate, six states had higher value than national average in case of hospital beds per lakh of population and nine states were above national average in case of ICU beds per lakh population. In availability of ventilators for serious patients, national average was four per lakh population whereas Delhi had the highest number of ventilators followed by Maharashtra, Punjab, Uttarakhand, and Himachal Pradesh. The number of COVID-19 testing laboratories in India was 2,655 with wide regional variation among states. Tamil Nadu had the highest number of laboratories for testing COVID-19, followed by Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Karnataka whereas Himachal Pradesh had the lowest number of laboratories, followed by Jammu and Kashmir, Jharkhand, Assam, and Chhattisgarh. The number of doctors in India was 92 per lakh population and nine states had higher value than the national average. Maharashtra had the highest doctors, followed by Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh. Moreover, Himachal Pradesh had the lowest number of doctors, followed by Jharkhand, Uttarakhand, Chhattisgarh, and Haryana.

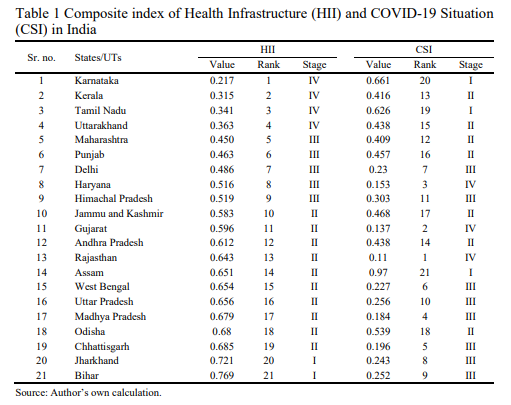

To overview the level of health infrastructure and to understand the impact of COVID-19 pandemic in India, a composite index of health infrastructure (HII) and COVID-19 situation (CSI) have been carried out, as given in Table 1.

It was clearly observed that Karnataka (0.217) obtained first place in health infrastructure followed by Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Uttarakhand with index value of 0.315, 0.341, and 0.363, respectively. On the other hand, Bihar (0.769) had very poor health infrastructure, after that Jharkhand with index value of 0.721. Bihar had the lowest number of hospital beds, ICU beds, ventilators, and labs for COVID-19 sample testing. In addition, Jharkhand also had a deficient number of ICU beds and doctors per lakh population.

On the other hand, from the values of the composite index of the COVID-19 situation, it may be observed easily that Rajasthan (0.110) obtained the first rank in this index, which means this state did well in the pandemic, followed by Gujarat and Haryana with index values of 0.137, and 0.153, respectively. Rajasthan performed better as it had a low fatality rate from the pandemic and vaccinated around 25 per cent of the population. Gujarat had a low positivity rate and vaccinated 31 per cent of the population; moreover, Haryana had observed a high recovery rate and vaccinated 23 per cent of the population. On the contrary, Assam (0.970) was the state most afflicted by the pandemic, followed by Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, with values of 0.661 and 0.626, respectively. Assam had the lowest recovery rate, and only 14 per cent of the population had been vaccinated.

From the above findings, it was found that all the four states with better health infrastructure failed to tackle the pandemic as expected. Similarly, two states with average infrastructure, Maharashtra, and Punjab, have also failed. With its average infrastructure, Haryana was the only state that did well. On the other hand, barring four states namely Jammu and Kashmir, Gujarat, Assam, and Odisha, all poor as well as very poor health infrastructure having states have fared better.

II District Level Analysis of Health Infrastructure and COVID-19 in Haryana

The primary objective of this section was to study the level of health infrastructure and situation of COVID-19 in Haryana. It was at 8th rank with average health infrastructure (III) among major states; whereas, a better situation (IV) with 3rd rank has been observed in the case of the COVID-19 situation among major states (see Table 1).

In terms of health infrastructure, Haryana had 601 hospitals, 41,744 hospitals beds and 69 testing laboratories dedicated to COVID-19. , Haryana had 2 hospitals per lakh population, 144 hospitals beds, seven ICU beds, four ventilators and merely 48 doctors. In terms of hospitals and doctors, the state was far below the

national average. However, Haryana was better in terms of hospital beds, ICU beds per lakh population, while the number of ventilators was almost equal to the national average. At the district level, Gurugram had the highest number of hospitals in terms of absolute as well as per lakh of population, whereas Sirsa had the least number of hospitals. Ambala had the highest number of hospital beds, whereas Yamunanagar had the least number of hospital beds. Moreover, Gurugram had the highest number of ICU beds and ventilators, whereas Nuh had the lowest number of ICU beds and Jind had the lowest number of ventilators. On the aggregate level, eight districts were above than the states’ average in case of number of hospitals per lakh population, and nine districts were above the states’ average in hospital beds. In terms of ventilator availability, Gurugram had the highest number of ventilators (22), per lakh population, and seven districts had higher values than the state average. Haryana had a total of 69 laboratories for testing COVID-19, in which Gurugram had the highest number of laboratories, followed by Faridabad, Ambala and Rohtak. In two districts, i.e. Kaithal and Mahendragarh, there was not even a single laboratory for COVID-19 sample testing. In terms of doctors per lakh population, about 48 doctors were available in Haryana, while Panchkula had the highest number of doctors (128), and Palwal had the least number of doctors (4).

Moreover, in Haryana, the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the Gurugram district on 17th March 2020. However, earlier on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization had declared COVID-19 as a pandemic and on the same day the Haryana Government issued the ‘Haryana Epidemic Diseases, COVID-19 Regulations, 2020. After that, in the year 2020, two rounds of Sero Survey (first in August and second in October 2020) were conducted by Health Department of Haryana to evaluate the spread of COVID-19 in different districts. In the first round, Faridabad was found the most affected district in the state where the positivity rate was found to be eight per cent. Moreover, in the second round of the Sero survey, Faridabad was again found the most affected district; however, this time the positivity rate had increased to 14.8 per cent. To measure the impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the districts of Haryana, a composite index of the ‘COVID-19 situation’ was calculated based on selected five indicators, as given in Table 2. In Haryana, the number of confirmed cases per lakh population was 2,652 as of 16th June 2021. In which, Gurugram (10,457) district had the highest number of confirmed cases, followed by Faridabad (4,828), Panchkula (4,766), and Sonipat (2844); whereas, Nuh (401) district had the lowest number of confirmed cases followed by Palwal (890), Kaithal (905), and Bhiwani (1,382). Hisar, Sonipat, Panchkula, Faridabad and Gurugram had higher value than the state average in confirmed cases. The fatality rate from COVID-19 was 1.19 per cent in Haryana, where only six districts had a lower fatality rate than the state average. Kaithal had the highest fatality rate, followed by Fatehabad, Bhiwani and Jind; whereas, Gurugram had the lowest fatality rate, followed by Sonipat, Mahendragarh and Faridabad. The recovery rate in Haryana was 98.34 per cent as of 16th June 2021, where merely four districts had a higher recovery rate than the

state average. Sonipat (99.45 per cent) had the highest recovery rate, followed by Gurugram (99.34 per cent), Mahendragarh (99.05 per cent) and Faridabad (99.04 per cent). On the other hand, Kaithal (96.14 per cent) had the lowest recovery rate, followed by Bhiwani (96.69 per cent), Jind (96.98 per cent) and Mahendragarh (97.39 per cent). As on June 16, 2021, 23.34 per cent of the total population in Haryana had been covered through vaccination (commutative coverage). Six districts of Haryana have vaccinated a larger population than the state average. Gurugram covered the highest 51.71 per cent population by vaccination, followed by Ambala, Panchkula, and Faridabad. The lowest vaccination was observed in Haryana in Nuh (6.88 per cent), followed by Jind, Hisar and Kaithal with 13.58,

14.29 and 15.95 per cent, respectively. The weekly positivity rate from 9th to 15th June 2021 was only one per cent in Haryana. As of 16th June 2021, only five districts were found a lower positivity rate than the state average. Highest positivity rate was observed in Sirsa (20.23 per cent), followed by Fatehabad, Rohtak and Panchkula at 6.09, 5.38, and 4.43 per cent, respectively. The lowest positivity rate was observed in Nuh (0.19 per cent) district, followed by Jhajjar, Mahendragarh and Gurugram at 0.33, 0.53 and 0.70 per cent, respectively.

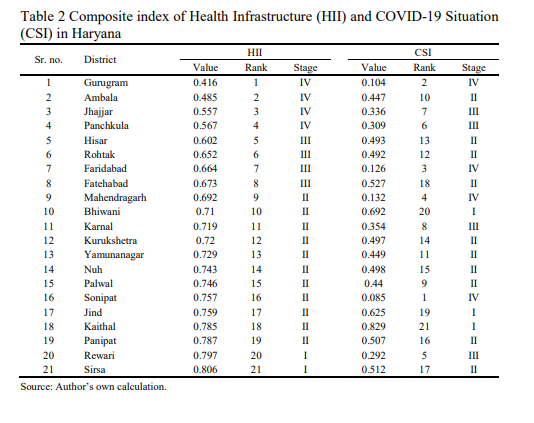

To overview the level of health infrastructure and to understand the impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Haryana, a composite index of health infrastructure (HII) and COVID-19 situation (CSI) have been carried out, as given in Table 2.

It was observed that Gurugram (0.416) district occupied the first rank in health infrastructure, followed by Ambala, Jhajjar and Panchkula with an index value of 0.485, 0.557, and 0.567, respectively. Whereas, Sirsa (0.806) district has the worst health facilities, followed by Rewari with an index value of 0.797. Whereas Sirsa (0.806) district has the worst health facilities, followed by Rewari with an index value of 0.797. It has found that more than half of the districts did not have available adequate infrastructure to deal with pandemic situation.

On the other hand, from the values of the composite index of the COVID-19 situation, it may be observed that Sonipat (0.085) district obtained the first rank in this index, which means this state did well in the pandemic, followed by Gurugram, Faridabad and Mahendragarh with an index value of 0.104, 0.126 and 0.132, respectively. All four districts have obtained better stage (IV) in COVID- 19 situation index as it had higher recovery rates, lower fatality and positivity rates, and higher percentage of the total population vaccinated than the state average. Whereas, Kaithal (0.829) district was the district most affected by the pandemic, followed by Bhiwani and Jind with an index value of 0.692 and 0.625, respectively. Kaithal had a lower recovery rate, higher fatality and positivity rate, and lower percentage of the total population vaccinated than the state average. From the above findings, it was found that except Gurugram and Faridabad districts, all the districts with better as well as average health infrastructure, had failed to tackle the pandemic situation as expected. On the other hand, five districts, namely Mahendragarh, Karnal, Sonipat, Rewari and Sirsa fared better, despite having poor or very poor health infrastructure.

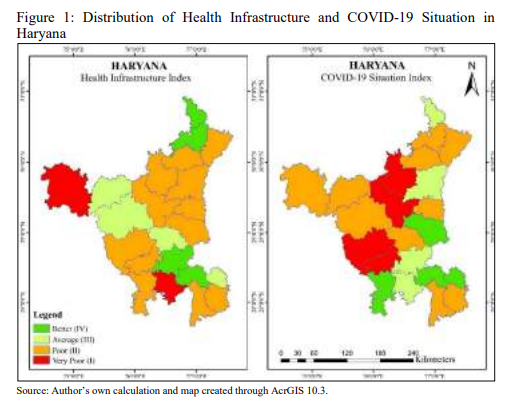

The district level stages of the health infrastructure index and COVID-19 situation index has been represented in Figure 1. In terms of health infrastructure, only 38.33 per cent of the population resides in the eight districts which had better or average infrastructure facilities . On the other hand, in terms of the COVID-19 situation index, only eight districts performed better or average in which 38 per cent of the population resides. It was clearly observed that a high proportion of the population of Haryana resides in the poor or very poor condition in both indices. Only one district, Gurugram, performed better in both indices. However, five districts namely, Kurukshetra, Yamunanagar, Nuh, Palwal and Panipat did poorly in both indices. The findings showed that a high variation exists in health infrastructure and the COVID-19 situation index at the district level in Haryana.

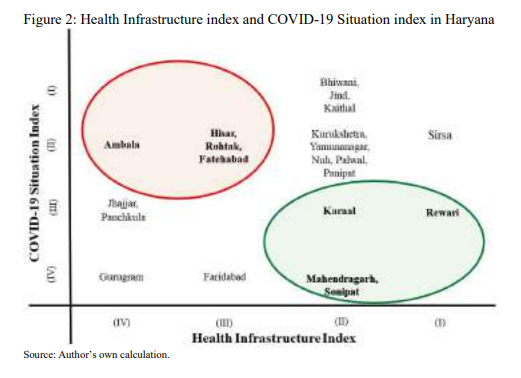

The interrelationship between health infrastructure index and COVID-19 situation index in districts of Haryana had been explained in Figure 2. In Haryana, out of 21 districts, eight districts had better (IV) or average (III) health infrastructure and the remaining 13 districts had poor (II) or very poor (I) health infrastructure. Moreover, in COVID-19 situation index, eight districts were situated in a better or average condition and the remaining 13 districts in poor or very poor situation. It can be clearly observed from Figure 2 that out of four districts having better health infrastructure, namely Ambala, Jhajjar, Panchkula and Gurugram, only Gurugram performed as expected with sufficient infrastructure. Moreover, Gurugram had the highest concentration of COVID-19 infection, followed by Faridabad, Panchkula, Sonipat and Hisar. However, Ambala was found in the poor circumstances in COVID-19. Jhajjar and Panchkula had an average situation according to the index value. Interestingly, Mahendragarh and Sonipat had poor in health infrastructure, although they performed better in COVID-19 pandemic. Karnal was also in poor infrastructure still occupied Stage III in health infrastructure index. Despite health infrastructure in Rewari district was very poor, it performed average (Stage III) in COVID-19 situation Index. Similarly, in COVID-19 situation index, four districts, namely Gurugram, Faridabad, Mahendragarh and Sonipat, were in better condition. Bhiwani, Jind and Kaithal were in very poor COVID-19 situation. Jhajjar, Panchkula, Karnal and

Rewari were in the average stage. Kurukshetra, Yamunanagar, Nuh, Palwal and Panipat were poor in health infrastructure as well as in COVID-19 situation index. Nuh had the lowest concentration of COVID-19 infection, followed by Palwal, Kaithal, Bhiwani and Jind.

V Conclusion and Policy Implications

The present study had focused on investigating the performance of health infrastructure and COVID-19 situation in India with special reference to Haryana. In this study, 21 major states/UTs of India were considered, in which Karnataka was found better in terms of health facilities and Bihar was very poor. However, despite having so many facilities, Karnataka performed very poorly in handling COVID-19 situation. On the other hand, five states, namely Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal, did not have a single indicator above the national average. In COVID-19 situation index, Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Haryana performed better and Assam, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu performed very poorly. In Haryana, Gurugram district occupied the first position in health infrastructure and Sirsa last. In health infrastructure, Hisar (5th rank) was the only district in which the values of all the indicators were higher than the state average. Moreover, three districts, i.e., Sirsa, Panipat, and Rewari, did not have a single indicator above the state average. In COVID-19 situation index, Sonipat, Gurugram, Faridabad, and Mahendragarh performed better and Kaithal, Bhiwani,

and Jind performed very poorly. Moreover, the relationship between the availability of health infrastructure in an area and their performance in COVID-19 situation was not clearly found. As a result, some areas with better infrastructure are struggling to cope with this pandemic situation, and some areas performed well despite having fewer health facilities. Therefore, it may be concluded that areas with better health infrastructure did not guarantee ability to tackle the pandemic situation. The government should focus on increasing testing capacity, rapid screening in rural areas, efficient management of containment zones at the micro- level, higher priority to the speedy vaccination, and more awareness programmes. COVID-19 pandemic exposed our infrastructural reality, and this is the time for the government to look at our policies and develop a more sustainable and affordable health mechanism for society.

References

Arif, M. and S. Sengupta (2021), Nexus between Population Density and Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in the South Indian States: A Geo-Statistical Approach, Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(7): 10246-10274.

Banerjee, A., M. Alsan, E. Breza, A.G. Chandrasekhar, A. Chowdhury, E. Duflo, P. Goldsmith- Pinkham and B.A. Olken (2020), Messages on COVID-19 Prevention in India Increased Symptoms Reporting and Adherence to Preventive Behaviors Among 25 Million Recipients with Similar Effects on Non-Recipient Members of Their Communities, NBER Working Paper No. 27496, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dev, S.M. and R. Sengupta (2020), Covid-19: Impact on the Indian Economy, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai, Retrieved from: http://www.igidr.ac.in/pdf/publication/ WP-2020-013.pdf.

Devender and J. Kumar (2021), Regional Disparities in Industrial Development in Haryana, Shodh Sanchar Bulletin, 11(41): 72-75.

Ewusi, K. (1976), Disparities in Levels of Regional Development in Ghana, Social Indicators Research, 3(1): 75-110.

Florek, K., J. Lukaszewicz, J. Perkal, H.I. Steinhaus and S. Zubrzycki (1952), Taksonomia Wroclawska, Przeglad Antropologiczny, Poznan, 17: 193-211.

Gauttam, P., N. Patel, B. Singh, J. Kaur, V.K. Chattu and M. Jakovljevic (2021), Public Health Policy of India and COVID-19: Diagnosis and Prognosis of the Combating Response, Sustainability, 13(6:3415): 1-18.

Gohel, K.H., P.B. Patel, P.M. Shah, J.R. Patel, N. Pandit and A. Raut (2021), Knowledge and Perceptions about COVID-19 among the Medical and Allied Health Science Students in India: An Online Cross-Sectional Survey, Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 9(1): 104-109.

Kannan, S., P.S.S. Ali, A. Sheeza and K. Hemalatha (2020), COVID-19 (Novel Coronavirus 2019)– Recent Trends, European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 24(4): 2006- 2011.

Khan, H. and I. Islam (1990), Regional Disparities in Indonesia: A Social Indicators Approach,

Social Indicators Research, 22(1): 69-81.

Kirti, and B. Langyan (2020), Performance of Health Sector Expenditure in Haryana: An Analytical View, Shodh Sanchar Bulletin, 10(40): 18-22.

Kumar, A. and S. Gupta (2012), Health Infrastructure in India: Critical Analysis of Policy Gaps in the Indian Healthcare Delivery, Vivekananda International Foundation, Retrieved from https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/health-infrastructure-in-india-critical-analysis-of- policy-gaps-in-the-indian-healthcare-delivery.pdf

Mac Arthur Foundation, India (2006), Government Health Expenditure in India: A Benchmark Study, Economic Research Foundation, New Delhi, Retrieved from: http://www.macroscan.org/anl/oct06/pdf/Health_Expenditure.pdf.

Malani, A., S. Soman, S. Asher, P. Novosad, C. Imbet, V. Tandel, A. Agarwal, A. Alomar, A. Sarker,

D. Shah, D. Shen, J. Gruber, S. Sachdeva, D. Kaiser and L.M.A. Bettencourt (2020), Adaptive Control of COVID-19 Outbreaks in India: Local, Gradual, and Trigger-based Exit Paths from Lockdown, NBER Working Paper No. 27532, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, Retrieved from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w27532

Maulik, C., B. Patil, R. Khanna, S.B. Neogi, J. Sharma, V.K. Paul and S. Zodpey (2016), Health Systems in India, Journal of Perinatology, 36(Suppl 3): S9–S12.

Media Bulletin on Corona Virus (2021), National Health Mission, Haryana, Retrieved from: http://nhmharyana.gov.in/page?id=208.

Narain, P., S.C. Rai and S. Shanti (1991), Statistical Evaluation of Development on Socio-Economic Front, Journal of Indian Society of Agricultural Statistics, 43(3): 329-345.

National Health Profile (2020), Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India, Retrieved from: https://www.cbhidghs.nic.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=1&sublinkid=75&lid=1135.

Ohlan, R. (2013), Pattern of Regional Disparities in Socioeconomic Development in India: District Level Analysis, Social Indicators Research, 114(3): 841-873.

Pandey, A., A. Prakash, R. Agur and G. Maruvada (2021), Determinants of COVID-19 Pandemic in India: An Exploratory Study of Indian States and Districts, Journal of Social and Economic Development, 23(Suppl 2): S248-S279.

Petropoulos, F., and S. Makridakis (2020), Forecasting the Novel Coronavirus COVID-19, PLOS ONE, 15(3): 1-8.

Press Information Bureau (2021), Media bulletin on COVID-19, Government of India, Retrieved from: https://covid19.india.gov.in/document-category/press-information-bureau.

Rekha, M. (2020), COVID-19: Health Care System in India, Health Care: Current Reviews, Short communication, 0(0): S1:262.

Riza, S.A., A. Erdogan, P.M. Agaoglu, Y. Dineri, A.Y. Cakirci, M.E. Senel, R.A. Okyay and A.M. Tasdogan (2019), Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak: A Review of the Current Literature, Eurasian Journal of Medicine and Oncology, 4(1): 1–7.

Sadanandan, R. (2020), Kerala’s Response to COVID-19, Indian Journal of Public Health, 64(6): 99-101.

Sahoo, H., C. Mandal, S. Mishra and S. Banerjee (2020), Burden of COVID-19 Pandemic in India: Perspectives from Health Infrastructure, Demography India, 49(special issue): 98-112.

Sarkar, K., S. Khajanchi and J.J. Nieto (2020), Modeling and Forecasting the COVID-19 Pandemic in India, Chaos, Solitons and Fractals, 139(10): 1-16.

Seethalakshmi, S. and R. Nandan (2020), Health is the Motive and Digital is the Instrument, Journal of the Indian Institute of Science, 100(4): 597-602.

Shukla, D., A. Pradhan and P. Malik (2021), Economic Impact of COVID-19 on the Indian Healthcare Sector: An Overview, International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 8(1): 489-494.

Singh, A., P.K.V. Deedwania, A.R. Chowdhury and P. Khanna (2020), Is India’s Health Care Infrastructure Sufficient for Handling COVID 19 Pandemic?, International Archives of Public Health and Community Medicine, 4(2): 1-4.

Singh, N. (2008), Decentralization and Public Delivery of Health Care Services in India, Health Affairs, 27(4): 991-1001.

Strand, M.A., J. Bratberg, H. Eukel, M. Hardy and C. Williams (2020), Community Pharmacists’ Contributions to Disease Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Preventing Chronic Disease, 17(E69): 1-8.

Sudhakara, H. and T.R. Prasad (2016), Health Care Expenditure in India – An Analysis, Shanlax International Journal of Economics, 5(1): 26-34.

Varkey, R.S., J. Joy and P.K. Panda (2020), Health Infrastructure, Health Outcome and Economic Growth: Evidence from Indian Major States, Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(11): 2002-2010.

Velavan, T.P. and C.G. Meyer (2020), The COVID 19 Epidemic, Tropical Medicine and International Health, 25(3): 278-280.

Wang, C., P.W. Horby, F.G. Hayden and G.F. Gao (2020), A Novel Coronavirus Outbreak of Global Health Concern, The Lancet, 395(10223): 470-473.

Weekly Operational Update on COVID-19 (2021), World Health Organization, Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19—15- june-2021.

World Health Organisation (2018), World Health Statistics Report, Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/publications/world-health-statistics.

———- (2021), Weekly Operational Updates on COVID-19, Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/india/home/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19).