The Gap between Increasing Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Years with Reference to Selected Indian States

June 2023 | P. Devi Priya

I Introduction

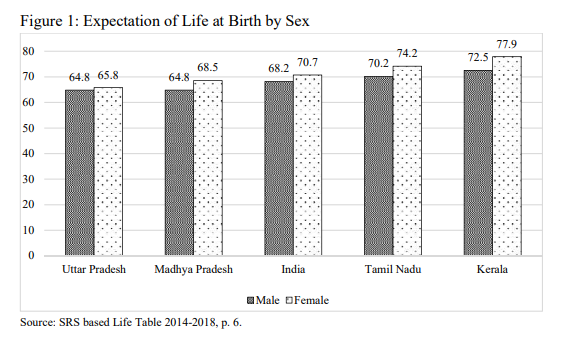

The goal of all health care systems is to attain good health status of the population. Increasing Life Expectancy (LE), decreasing death rates and disaster management in times of outbreak of new epidemics are indicators of health outcome. In 1951, the Crude Death rate in India was 25.1 (MOHFW 2015). In 2018 it fell to 6.2. Life expectancy at birth in India was 37.1 and 36.1 years respectively for males and females in 1951. It increased to 68.2 and 70.7 years in 2014-2018 for males and females respectively. The record of declining mortality and increasing expectation of life years since independence were successes in terms of human resource development. However, the potential increase in life years is optimal only when the enhancement in LE is backed by a healthy life, which results in the true attainment of health status. As one of its quantitative goals, the National Health Policy 2017 has recommended assessing the health status by ascertaining a regular follow-up of the Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALY), a measure of burden of disease and its major categories and trends by 2022. DALY is an index that shows the expected healthy years in the expected lifespan of an individual. The pioneer study on Disability Free Life Expectancy in India was based on the methodology of Sullivan (1971). It used the National Sample Survey 60th round, 2004 data for analysis and concluded that states which had registered high LE had a higher rate.

Statement of the Problem

A comparison between 20 major states in India with the data from the Sample Registration System Bulletin 2020 indicates that Kerala and Tamil Nadu had the lowest birth rate and infant mortality rate, while Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh were in the top three. However, all four states had death rates higher than the national average.

The abridged life table for 2014-2018 portrayed in Figure 1 reveals that the expected life years in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh were below national status, whereas Kerala and Tamil Nadu lead in the parameters, indicating a good sign of advancement.

Two high-performing and two low-performing states in terms of health were considered for the study. Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh were the four states selected for a comparative analysis. The better-achieving states in terms of public health services were Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh registered high birth and death rates much above the national average. They were the two low-performing states selected.

The paper attempts to analyse whether the mortality improving states enjoy the extra life years gained in good health status and also the status of states lagging behind. The disaggregated analysis was examined with the demographic tool’s life expectancy and health-adjusted life expectancy.

Objectives

The specific goal was to investigate the disparities in population health status in the four selected states: Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, combining mortality (2009-2013) and morbidity (2014) by region and sex.

Methodology

Unit-wise data from National Sample Survey 71st round 2014 was used to estimate the morbidity at birth and at 60 years in the selected four states. A five-year average of Age Specific Death Rates (ASDR) from 2009-2013 was used to generate abridged life tables. ASDR was consolidated from the statistical reports of Sample Registration System for the respective years. The disability adjusted life years (DALY) was obtained by subtracting expected life years without ailment and the years lived with ailments (Benson, et. al. 2014).

The two levels of ailment considered for construction of DALY were

- Proportion of ailing persons (Morbidity)

- Proportion of people with restricted activity (RA)

Morbidity: The proportion of ailing persons included chronic ailments and other ailments perceived, which were both treated and untreated. In the computation of morbidity rates, they were considered mutually exclusive for an individual. The perceived illnesses were partially likely to be biased since they were not from medical records, but the other measure Restricted Activity corresponding to the actual disability suffered.

Restricted Activity: RA refers to the inability of a person to carry out any part of his normal activities on account of his ailment. Only that which occurs due to the ailment was considered. For economically employed persons, it means abstention from economic activity. For housewives, it means cutting down on the day’s chores. In case of retired persons, it means pruning of his/her regular activity. For students, it means absence from attending classes.

II Rate of Ailments

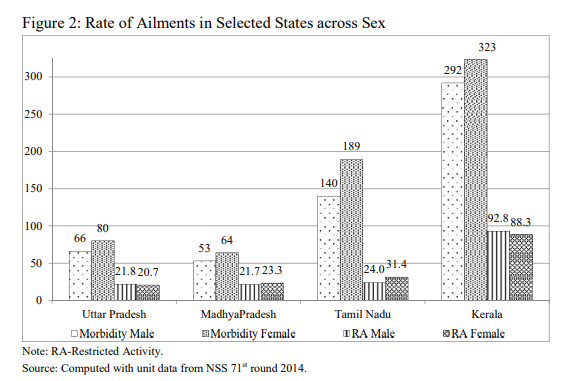

The morbidity and restricted activity rates depicted in Figure 2 reveal an exceptional situation. The estimated morbidity rate of Kerala and Tamil Nadu was higher than the national level. Kerala, the model state, has recorded the highest rates. Though in terms of restricted activity, its intensity was less, compared to the least performing states, it was four times ahead. However, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh recorded the reverse pattern of less than the national average in both

the estimated rate of illnesses. The mismatch in trend was observed between high and low performing states.

Morbidity Adjusted Life Expectancy

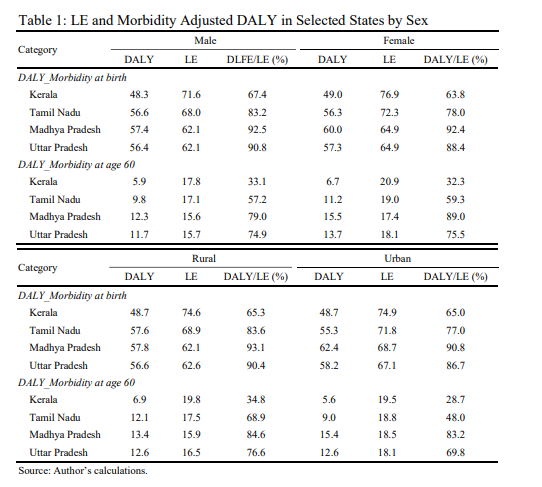

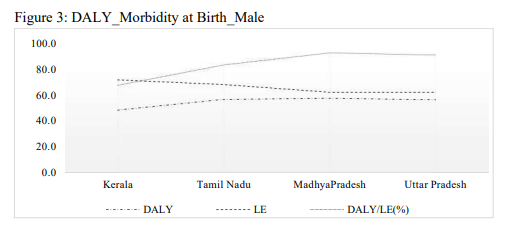

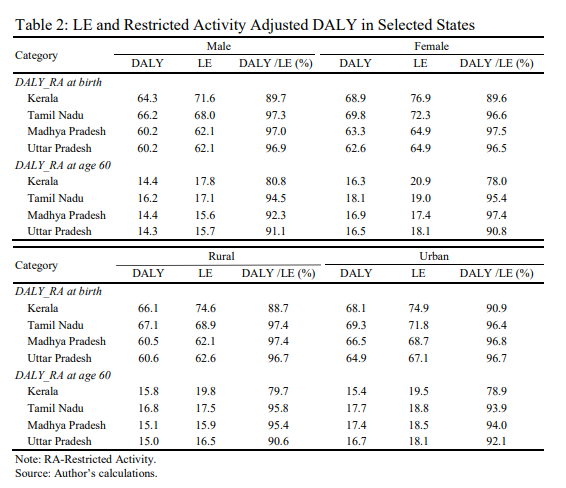

The computed life expectancy from the Age Specific Death Rates 2009-2013 exhibits a similar pattern as Figure 1 for the selected states. Table 1 shows that females and urban life expectancy at birth and at age 60 were both higher than their counterparts, males and rural people, in all the selected four states except Kerala where it was almost equal irrespective of place of residence. The framework of computed DALY was used to assess a person’s healthy expected life time years.

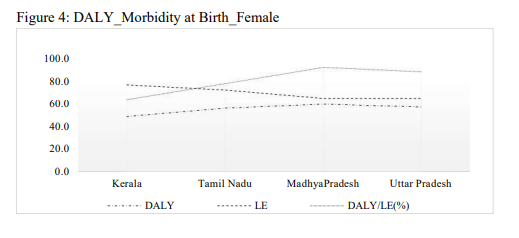

a. Sex-Wise Differentials

The life expectancy at birth in Kerala for males and females was 72 and 77 years respectively. The share of healthy years lost due to morbidity was 36 per cent for females and 33 per cent for males. In Tamil Nadu the life expectancy at birth for males and females was 69 and 72 years respectively. Males had 83 per cent proportion of life years free of illness to their expected years, while females had only 78 per cent proportion. This implies that diseases consume17 per cent male and 22 per cent female life years. In Madhya Pradesh five years (eight per cent) for females and five years (seven per cent) for males were lost due to morbidity.

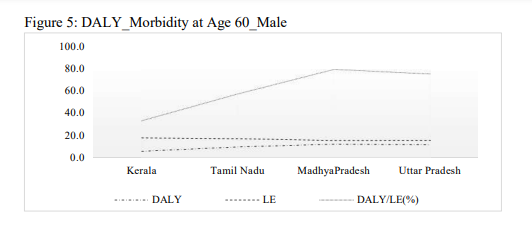

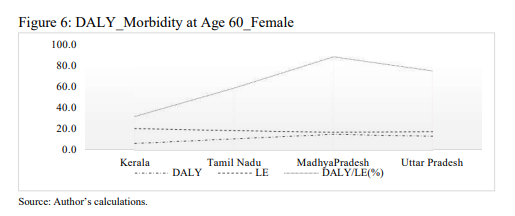

In Uttar Pradesh, 12 per cent females and nine per cent males live in sickness. Males have shorter life expectancies than females, but there is less morbidity during their expected life period. Kerala exhibits lesser disability-free years compared to other three states. At age 60 this was still worse in Kerala, with disability free life years only 33 per cent for males and 32 per cent for females. This demonstrates that Tamil Nadu and Kerala had both high morbidity and low mortality rates. Curative medical care has condensed only the fatality rate without sustained improvement in nutrition, water supply and sanitation (Irudhaya Rajan and James 1993, Suryanaryana 2008).

b. Region-Wise Differentials

In Kerala, morbidity costs 29 years (35 per cent) of life, regardless of the place of residence. Despite the fact that the expectation of life years at birth in Tamil Nadu for rural masses (70 years) was lower than for urban folks (73 years)by three years, the quality-of-life for people in urban region was described as disadvantaged. In Madhya Pradesh nine per cent of urbanites’ lives and seven per cent of ruralites’ lives were lost due to morbidity. In Uttar Pradesh the figures were 13 per cent and 10 per cent respectively. Though the life expectancy was low, the predictions of healthy living years were high in rural areas. In Tamil Nadu, compared to the other three states, there was a significant disparity between rural and urban children in terms of disability-free life years. Rural children were seven per cent better off at birth than their counterparts in Tamil Nadu. Though health- care facilities were more readily available in cities, the externalities of urbanisation, food practices, sedentary lifestyles and pollution outweigh rural life. Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh reveal a reverse trend of relatively lesser life expectancy but a higher per cent of disability-free life years for all categories. Thus, it was obvious that there was high frequency of diseases with minimum physical infirmities. Seeking health care, treatment actions and proper follow-up intervention at the right time had reduced physical disabilities in the better performing states. The dominance of non-fatal illnesses was negatively correlated with expected additional healthy life years.

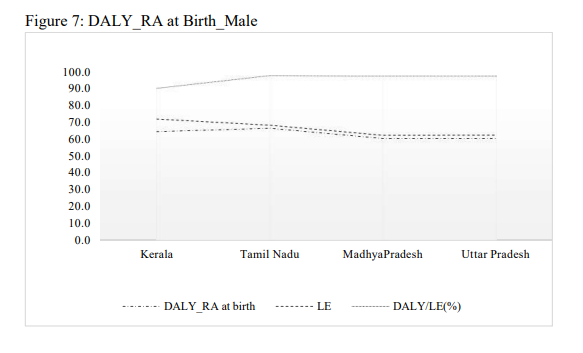

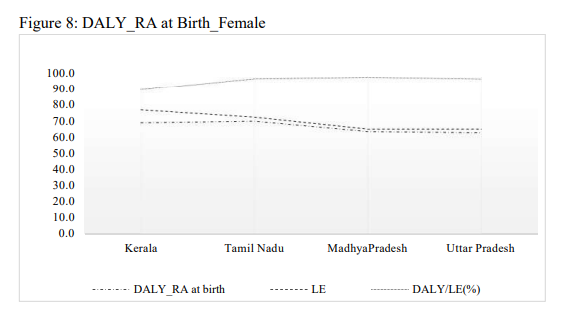

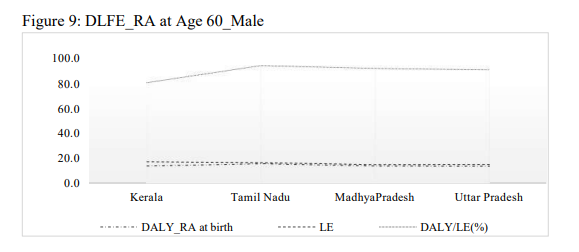

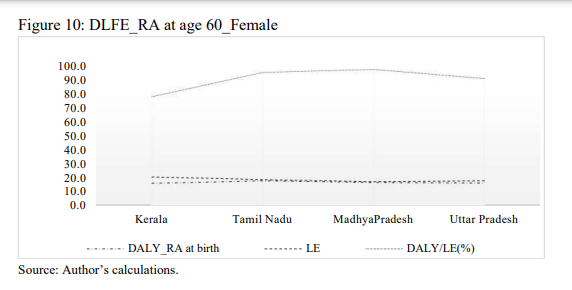

II Restricted Activity Adjusted Life Expectancy

The restricted activity episodes represent the people’s inability to carry on activities such as work, housework or school attendance. DALY combined with RA (DALY_RA) was higher for females than males and urban people than rural people, except for the elderly in Kerala, where rural folks were slightly in an advantageous position compared to urban people (Table 2). The percentage of restriction free life years in selected three states, except Kerala, was above 90 per cent. For elderly people, the RA adjusted DALY was again higher in urban areas than in rural areas. Very few senior citizens who have retired from jobs in the organised sector, generally located in urban areas, earn retirement benefits. Most senior citizens, even in poor health, have to do some kind of labour to earn their livelihood. The elderly have greater obstacles as a result of urbanisation, fewer children and nuclear families. They encounter a wide range of health challenges, including heterogenous ones like sensory impairment, infections and degenerative diseases. Apart from socio-economic inequalities, the needs differ. Along with good geriatric care, children should provide special care, particularly to grandmothers.

II Discussion

The DALY is a metric that quantifies the overall health effect linked to both morbidity and mortality. It summarises the population’s overall health and compares regions in a single value. The findings reveal comparable tendencies to those found in international studies. The studies on two London districts revealed gender and area differences in DALY (Dodhia and Phillips 2008). The progressive increase in quality adjusted life years (QALY) among United States adults as a result of a consistent decline in mortality rates varied by subgroups. People with chronic illnesses lost more QALY’s than those without illness among adults over the age 65 (Haomiao, et. al. 2011 and 2016). In Italy, it was concluded that the health improvements had rejuvenated ageing besides the emerging gender gaps in survival conditions (Elena Demuru and Viviana Egidi 2016). A United States surgeon reported that the health of the population was determined largely by lifestyle (50 per cent) followed by biological and environmental factors (20 per cent each), whereas health system-related factors contribute only 10 per cent (MOHFW 2017 b). Smoking, high alcohol consumption, physical inactivity and obesity reduce life expectancy and health related quality of life in Denmark (Henrik, et. al. 2007).

Nevertheless, it was claimed that diabetes was prevalent even among the poor in India, indicating that it was not due to lifestyle choices but due to the impact of under-nutrition, which causes chronic health problems (Vikas Bajpai 2018). The data on monthly per capita kilograms of food consumption in rural and urban areas describes the lower intake of vegetables and the higher intake of packaged processed foods (NSSO Report 558, 2014). On an average, a person consumes more than one kilogram of packed processed food a day. This contemporary custom proved detrimental to living a healthy lifestyle. Diabetes and hypertension were consequences of the consumption of fast foods, which leads to obesity and an increase in cardiovascular diseases. Tobacco use, an unhealthy diet and lack of physical activity all increase the risk of chronic illnesses.

According to the draft National Health Policy 2015, overcrowded public health hospitals, address less than 15 per cent of all morbidities, forcing people to seek private care. Therefore, among rural people, there were more chances for not only untreated illness but also unidentified diseases. The self-perceived illness included morbidity, which may lead to over-reporting by females and urbanites or under-reporting by males and rural residents, so the chronic illness rate was also calculated from the unit data (Appendix I). Tamil Nadu and Kerala ranked exorbitantly high in chronic illness rate compared to Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, registering the least at national level. The lifestyle-practices of urban people have resulted in high prevalence of chronic illness among them. The rural- urban disparities in the rate of chronic illness were high compared to male-female differences. This authenticates that disability adjusted life years estimated for the state across groups were neither over nor under reported. Chronic illness diagnosis has to be instigated scrupulously in all public care institutions to enable early

detection. It suggests that, during the transition period, Kerala and Tamil Nadu had to focus on improving timely and accurate diagnosis of chronic diseases. Subsequently, chronic illnesses remain symptomless for an elongated time period. More attention needs to be given to early detection so as to manage the illness with less loss. Instantaneously, preventive behavioural practices like dietary changes and exercises would help to combat life with disabilities. The increase in life span caused by the demographic transition has been accompanied by diseases and disability caused by high nutrient calorie intake and less physical activity, as well as the epidemiological transition. The Indian health structure, despite the epidemiological transition, was unable to re-orient itself to effectively address the intensifying problem of degenerative diseases as the focus was still largely on providing acute care and not on providing chronic care (Sailesh Mohan and Prabhakaran 2014).

In times of health crisis, Tamil Nadu has reacted effectively. For instance, during the outbreak of leptospirosis in the government medical college in Chennai, the health inspectors from nearby districts were posted to carry out preventive measures. Due to lack of this effort, Delhi experienced dengue outbreaks that originated from medical colleges (Monica, et. al. 2010). The public health system plays added role to the curative medical part. Despite its low per capita income, Kerala’s social overhead capital development of high literacy, high life expectancy, improved access to health care, low infant mortality and low birth rates has placed the state’s metrics on par with developed nations, establishing the state as a Kerala model of development.

To identify the prevalent illness, health seeking behaviour in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh needs to be improved. The proportion of the population served by public care in Uttar Pradesh was lower than the national average. Low life expectancy was chiefly caused by preventable child deaths, low institutional delivery, and lack of access to piped water and sanitation facilities. A study concluded that in Madhya Pradesh, half of the public district hospitals were technically inefficient in providing maternal health care services (Tej Ram Jat and Miguel San Sebastian 2013).

In all four states, the years of DALY were less than years of life expectancy, implying high morbidity. The better-performing states were unable to take fuller advantage of longer lives, while in undeveloped states, most of the illness were left undiagnosed.

Implications

- Proper identification of diseases at the right time to be improved.

- Long-term disease diagnosis has to be rigorously done in the public health care centres and adequate restorative care to be made available persistently.

- Sufficient geriatric care facilities need to be inbuilt in the system as well as in the families.

- People’s access to adequate public health care in low-performing states, particularly rural areas must be addressed.

- Malnutrition must be eradicated. The availability and responsiveness of low- cost nutritious food has to be instilled in the community, particularly among the city dwellers.

- Undertake massive public awareness initiatives to promote physical activity and healthy lifestyle behaviours.

III Conclusion

Appropriate precautionary measures could combat the incidence of chronic illness. Satisfactory health care, timely availability and affordability of health systems at the onset would diminish the intensity of long-term diseases. Additional years of life gained should not be mere deferment of mortality and life filled with disabilities and discomfort. Henceforth, proper progeny care and financial independence must be assured to overcome the elderly’s health needs. The decrease in mortality and the subsequent upsurge in life expectancy accompanied by the decline in incidence of morbidity can be made possible by a planned comprehensive health care system with the inclusion of preventive, curative and restorative measures along with adequate care. An increase in longevity with outstanding geriatric care will help in transforming them into a productive, experienced resource force for the nation.

References

Bajpai, Vikas (2018), National Health Policy, 2017 Revealing Public Health Chicanery, Economic and Political Weekly, LIII(28): 31-35.

Demuru, Elena and Viviana Egidi (2016), Adjusting Prospective Old-Age Thresholds by Health Status: Empirical Findings and Implications, A Case Study of Italy, Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 131-154, Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/ 26506086

Devi Priya, P. (2017), A Study on Utilisation and Expenditure of Health Care Services in Madurai District, Unpublished Thesis, Madurai: Madurai Kamaraj University.

Dodhia, H. and K. Phillips (2008), Measuring Burden of Disease in Two Inner London Boroughs using Disability Adjusted Life Years, Journal of Public Health, 30(3): 313-321, Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/45157706

Garg, Charu C., J. Pratheeba and Jyotsna Negi (2018), Utilisation of Health Facilities for Childbirth and Out-of-pocket Expenditure, Economic and Political Weekly, LIII(42): 53-61.

Haomiao, Jia and Erica I. Lubetkin (2016), Impact of Nine Chronic Conditions for US Adults Aged 65 Years and Older: An Application of a Hybrid Estimator of Quality-Adjusted Life Years Throughout Remainder of Lifetime, Quality of Life Research, 25(8): 1921-1929, Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/44852484

Haomiao, Jia, Matthew M. Zack and William W. Thompson (2011), State Quality-Adjusted Life Expectancy for U.S. Adults from 1993 to 2008, Quality of Life Research, 20(6): 853-863, Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/41488143

Henrik, Brounnum-Hansen, Knud Juel, Michael Davidsen and Jan Sorensen (2007), Impact of Selected Risk Factors on Quality-Adjusted Life Expectancy in Denmark, Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 35(5): 510-515, Retrieved from http://www.jstor.com/stable/ 45149891

Jat, Tej Ram and Miguel San Sebastian (2013), Technical Efficiency of Public District Hospitals in Madhya Pradesh, India: A Data Envelopment Analysis, Global Health Action, 6 (21742):1-8, DOI: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.21742

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2015a), Health and Family Welfare Statistics in India 2015,

New Delhi: Government of India.

———- (2015b), National Health Policy 2015 Draft, Retrieved January 26, 2015, from http://www.mohfw.nic.in/showfile.php?lid=3014

———- (2017a), National Health Policy, 2017, New Delhi: Government of India.

———- (2017b), Situation Analysis: Backdrop to the National Health Policy 2017, New Delhi: Government of India.

Mohan, Sailesh and D. Prabhakaran (2014), Non-Communicable Diseases in India: Challenges and Implications for Health Policy, In IDFC Foundation, India Infrastructure Report 2013|14, pp. 213-222, New Delhi: Orient Blackswan Private Limited.

Monica, G., et. al. (2010), How Might India’s Public Health Systems Be Strengthened? Lessons from Tamil Nadu, Economic and Political Weekly, XLV(10): 46-60.

National Sample Survey Organisation (2014), Household Consumption of Various Goods and Services in India 2011-12, NSS 68th Round, Report No. 558, Government of India: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

———- (2015), Health in India, NSS 71st Round, Report No.574, Government of India: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

Radhakrishna, Rakshit and C. Ravi (2004), Malnutrition in India: Trends and Determinants,

Economic and Political Weekly, 39(7): 671-676.

Rajan, Irudhaya and K. James (1993), Kerala’s Health Status: Some Issues, Economic and Political Weekly, 28(36): 1889-1892.

Sullivan, Daniel (1971), A Single Index of Mortality and Morbidity, HSMHA Health Reports, 86(4): 347-354.

Sundararaman, T., Indranil Mukhopadhyay and V.R. Muraleedharan (2016), No Respite for Public Health, Economic and Political Weekly, LI(16): 39-42.

Suryanarayana, M. (2008), Morbidity and Health Care in Kerala: A Distributional Profile and Implications, Working Paper 2008-004, Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.

Thomas, M. Benson, K. James and S. Sujala (2014), Does Living Longer Mean Living Healthier? Exploring Disability-free Life Expectancy in India, Working Paper 322, Bangalore: Institute of Economic and Social Change.

Appendix I

Rate of Chronic Ailments and Selected States in India by Sex and Region

| State | Total | Male | Female | Rural | Urban |

| Kerala | 208 | 186 | 229 | 201 | 217 |

| Tamil Nadu | 103 | 89 | 116 | 86 | 120 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 20 | 19 | 22 | 17 | 30 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 25 | 23 | 27 | 23 | 34 |

| India | 48 | 42 | 55 | 40 | 67 |

Source: Computed from NSS71st round unit data.

R.B.R.R. Kale Memorial Lectures at Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics

+ 1937 Modern Tendencies in Economic Thought and Policy by V.G. Kale 1938 The Social Process by G.S. Ghurye

- 1939 Federation Versus Freedom by B.R. Ambedkar

+ 1940 The Constituent Assembly by K.T. Shah

- 1941 The Problem of the Aborigines in India by A.V. Thakkar

- 1942 A Plea for Planning in Cooperation by V.L. Mehta 1943 The Formation of Federations by S.G. Vaze

+ 1944 Economic Policy by John Mathai

+ 1945 A Statistical Approach to Vital Economic Problems by S.R. Deshpande

+ 1946 India’s Sterling Balances by J.V. Joshi

- 1948 Central Banking in India: A Retrospect by C.D. Deshmukh

- 1949 Public Administration in Democracy by D.G. Karve 1950 Policy of Protection in India by R.L. Dey

1951 Competitive and Cooperative Trends in Federalism by M. Venkatrangaiya 1952 The Role of the Administrator: Past, Present and Future by A.D. Gorwala

+ 1953 Indian Nationalism by Laxmanshastri Joshi

1954 Public Administration and Economic Development by W.R. Natu

+ 1955 Some Thoughts on Planning in India by P.C. Mahalanobis

1956 Reflections on Economic Growth and Progress by S.K. Muranjan 1957 Financing the Second Five-Year Plan by B.K. Madan

+ 1958 Some Reflections on the Rate of Saving in Developing Economy by V.K.R.V. Rao 1959 Some Approaches to Study of Social Change by K.P. Chattopadhyay

- 1960 The Role of Reserve Bank of India in the Development of Credit Institutions by B. Venkatappiah

1961 Economic Integration (Regional, National and International) by B.N. Ganguli 1962 Dilemma in Modern Foreign Policy by A. Appadorai

- 1963 The Defence of India by H.M. Patel

- 1964 Agriculture in a Developing Economy: The Indian Experience (The Impact of Economic Development on the Agricultural Sector) by M.L. Dantwala

+ 1965 Decades of Transition – Opportunities and Tasks by Pitambar Pant

- 1966 District Development Planning by D.R. Gadgil

1967 Universities and the Training of Industrial Business Management by S.L. Kirloskar 1968 The Republican Constitution in the Struggle for Socialism by M.S. Namboodripad 1969 Strategy of Economic Development by J.J. Anjaria

1971 Political Economy of Development by Rajani Kothari

+ 1972 Education as Investment by V.V. John

1973 The Politics and Economics of “Intermediate Regimes” by K.N. Raj 1974 India’s Strategy for Industrial Growth: An Appraisal by H.K. Paranjape 1975 Growth and Diseconomies by Ashok Mitra

1976 Revision of the Constitution by S.V. Kogekar

1977 Science, Technology and Rural Development in India by M.N. Srinivas 1978 Educational Reform in India: A Historical Review by J.P. Naik

1979 The Planning Process and Public Policy: A Reassessment by Tarlok Singh

- Out of Stock + Not Published No lecture was delivered in 1947 and 1970

R.B.R.R. Kale Memorial Lectures at Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics

| 1980 | Problems of Indian Minorities by Aloo J. Dastur | |

| 1981 | Measurement of Poverty by V.M. Dandekar | |

| 1982 | IMF Conditionality and Low Income Countries by I.S. Gulati | |

| * | 1983 | Inflation – Should it be Cured or Endured? by I.G. Patel |

| 1984 | Concepts of Justice and Equality in the Indian Tradition by M.P. Rege | |

| 1985 | Equality of Opportunity and the Equal Distribution of Benefits by Andre Beteille | |

| 1986 | The Quest for Equity in Development by Manmohan Singh | |

| 1987 | Town and Country in Economy in Transition by K.R. Ranadive | |

| 1988 | Development of Development Thinking by Sukhamoy Chakravarty | |

| 1989 | Eighth Plan Perspectives by Malcolm S. Adiseshiah | |

| 1990 | Indian Public Debt by D.T. Lakdawala | |

| 1991 | Public Versus Private Sector: Neglect of Lessons of Economics in Indian Policy Formulation by B.S. Minhas | |

| 1992 | Agricultural and Rural Development in the 1990s and Beyond: What Should India Do and Why? by V. Kurien | |

| 1993 | An Essay on Fiscal Deficit by Raja J. Chelliah | |

| 1994 | The Financing of Higher Education in India by G. Ram Reddy | |

| 1995 | Patenting Life by Madhav Gadgil | |

| 1996 | Constitutional Values and the Indian Ethos by A.M. Ahmadi | |

| 1997 | Something Happening in India that this Nation Should be Proud of by Vasant Gowariker | |

| 1998 | Dilemmas of Development: The Indian Experience by S. Venkitaramanan | |

| 1999 | Post-Uruguay Round Trade Negotiations: A Developing Country Perspective by Mihir Rakshit | |

| 2000 | Poverty and Development Policy by A. Vaidyanathan | |

| 2001 | Fifty Years of Fiscal Federalism in India: An Appraisal by Amaresh Bagchi | |

| + | 2002 | The Globalization Debate and India’s Economic Reforms by Jagdish Bhagwati |

| 2003 | Challenges for Monetary Policy by C. Rangarajan | |

| + | 2004 | The Evolution of Enlightened Citizen Centric Society by A.P.J. Abdul Kalam |

| 2005 | Poverty and Neo-Liberalism by Utsa Patnaik | |

| 2006 | Bridging Divides and Reducing Disparities by Kirit S. Parikh | |

| 2007 | Democracy and Economic Transformation in India by Partha Chatterjee | |

| 2008 | Speculation and Growth under Contemporary Capitalism by Prabhat Patnaik | |

| 2009 | Evolution of the Capital Markets and their Regulations in India by C.B. Bhave | |

| + | 2010 | Higher Education in India: New Initiatives and Challenges by Sukhadeo Thorat |

| 2011 | Food Inflation: This Time it’s Different by Subir Gokarn | |

| 2012 | Innovation Economy: The Challenges and Opportunities by R.A. Mashelkar | |

| + | 2014 | World Input-Output Database: An Application to India by Erik Dietzenbacher Subject |

| + | 2015 | Global Economic Changes and their implications on Emerging Market Economies by |

| + | 2016 | Raghuram Rajan SECULAR STAGNATION-Observations on a Recurrent Spectre by Heinz D. Kurz |

| + | 2017 2019 | Role of Culture in Economic Growth and in Elimination of Poverty in India by N. R. Narayana Murthy Central Banking: Retrospect and Prospects by Y. Venugopal Reddy |

| + | 2020 | Introduction to Mechanism Design by Eric Maskin |