Caste and Enterprise Ownership: Emerging Trendsand Diversification in India

December 2023 | Gautam Kumar

Gautam Kumar

The caste system is the bedrock of Indian society. It confers rights and duties according to one’s status in the hierarchy of the caste system. Historically, Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) have faced restrictions on access to productive assets such as land, capital, credit, business etc. SCs also faced discrimination and unfavourable exclusion in public spheres of life, leading to unemployment among SCs. The caste system has influenced employment opportunities for SCs. From this perspective, the paper explores the role of caste in enterprise ownership with respect to the recent economic census 2015-2016, NSS 73rd round 2015-2016 and analyses the determinants of diversification and growth.

Keywords: Caste, Discrimination, Affirmative action, Entrepreneurship, Diversification

Introduction

Caste is one of the most important characteristics of the Indian society. The caste system is a system of stratified social hierarchy (Bayly 1999). Caste determines the economic and social rights of an individual in society. “Caste System is not merely a division of labour; it is also a division of labourers” (Ambedkar 1990). The caste system segregates labourers and confines them within distinct categories, establishing a hierarchy where workers are ranked in a stacked manner. Broadly, the caste system refers to the Varna and Jati systems. Historically,

the Hindu society was divided into a four-tier caste system comprising Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors, noble), Vaishyas (commoners, traders, agriculturists), and Shudras (servants) (Deshpande 2013). Brahmins came at the top of the hierarchy, and Shudras were considered to be at the bottom of the hierarchy. As per Hindu religious texts, the untouchables were excluded from the Varna system, resulting in their distinct treatment from the savarnas (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras). In the constitution of India, these untouchables are classified as Scheduled Castes (SCs).

Historically, caste or Jati is a localised system in which a community is associated with traditional occupations (Srinivas 2003). Jatis are ranked based on their Varna status. Hereditary and Endogamy are the two essential features perpetuating the caste system (Rodrigues 2019).

Caste gives economic opportunities and occupations to the people; it does not allow individuals to adjust to changing economic opportunities. Various occupations were designated for upper castes (also referred to as forward castes or Swarnas); on the other hand, some occupations considered polluted were assigned to certain castes considered lower castes/untouchables. SCs are clustered in the least-paid professions, such as casual labour, manual labour, sanitation, and leather-related work. The poverty rate among SCs and STs is significantly higher than other social groups (Strategy for New India @75, NITI Aayog 2018). SCs and STs have higher labour force participation rates and unemployment rates than other social groups. The periodic labour force survey 2021-2022 shows that more than one-third of casual labour belongs to SCs, more than three-fourths of sanitation workers are SCs; they have a disproportionately higher share in low- paying jobs but a meagre share in professional businesses and higher paying white- collar jobs except public sector (PLFS 2021-22).

Representation of all sections of society in public spaces, education, the health sector and the market is a pre-requisite for economic growth and inclusive development. If a large section of society remains outside the development process, it can generate resentment, harming growth (Deshpande 2013). To ensure the representation of marginalized sections such as SCs and STs, the Constitution of India has adopted a unique quota based affirmative action policy in the legislative assembly, public sector jobs and public-educational institutions.

The informal sector dominates the Indian economy, and more than 90 per cent of our labour force is engaged in the private sector, outside the purview of Reservation policies. Various studies (Deshpande and Newman 2007, Madheswaran and Attewell 2007, Thorat and Attewell 2007) show the extent of discrimination in the urban private sector. Multiple studies provide empirical evidence on unexplained wage differences partly caused by discrimination in the labour market (Madheswaran 2010, Thorat and Attewel 2007, Thorat, Madheswaran and Vani 2021). These studies established that social identity shaped outcomes in the labour market even when there is no difference in the endowments such as educational qualification and skills.

Entrepreneurship is another important sector which provides economic opportunities to people. It is generally assumed that markets are perfectly competitive, and there are no barriers to entry of firms (Neo-classical Economics). Firms can enter and exit irrespective of the identity of the owners of firms. By examining data related to the involvement of SCs and STs in owning enterprises, it becomes evident that inter-caste disparity exists, which highlights the impact of social identity on economic outcomes within the market. “Community, capital and credit—the three Cs—have played a major role in establishing community-based business houses in India. The principal formula of community-based businesses has been that the community comes together and creates capital. The capital is then distributed as credit within the community” (Mehrotra 2020).

This paper first presents a brief overview of existing literature in this area. Then it explores the participation of SCs in enterprise ownership, focusing on the recent NSS 73rd round 2015-2016 and the Sixth Economic Census 2015-2016. The paper examines the role of caste in enterprise ownership, growth and diversification and its explanation in the light of existing literature and theories of Economic Discrimination. The last section deals with policy implications.

I Why Group Inequalities Need to be Studied

Some historical examples of social mobility show that participation in the business sector and enterprise ownership played a significant role in social mobility. “Ownership of small businesses has been an important factor in the economic success and mobility of immigrant groups such as Chinese, Koreans, Jews, Italians in the United States, and ethnic minorities in England and Wales” (Clark and Drinkwater 2000). There are some prerequisites for that, such as equitable opportunity in factor markets, i.e., land, credit, commodities market: large numbers of these self-employment activities should have entrepreneurship tendencies rather than survival, etc. Analysis of the small businesses sector in India shows that SCs and STs have a disproportionately lower participation in business ownership, relative to their share in the population; SC and STs enterprises are concentrated in rural areas; these enterprises are survivalist in nature than entrepreneurial nature and these firms are smaller, with less share in workers employed.

II Caste as Social Capital

Social capital depicts the network of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, interpersonal relationships, a sense of shared norms, shared identity, shared understanding, shared values, trust and cooperation. It comprises the value of tangible resources (private property, public spaces, etc.), intangible resources (human capital, managerial talent, etc.), and shared relationships within the group. It will lead to enhanced supply chain relations and improved performance of entrepreneurial firms. It can be categorized into sub- types, such as Bonded social capital (within homogeneous groups), Binding social capital (across heterogeneous groups), etc. A variety of research shows that social capital positively correlates with financial inclusion, group membership increases the probability of getting an informal loan and positively correlates with employment, etc.

Robert Putnam has shown how group members gain enormous benefits from social capital (Vaidyanathan 2019). He showed how trust based on social capital reduced risk and cost, thus encouraging enterprises and innovation, which led to the growth of these enterprises owned by a particular social group. Caste works as social capital in the sense that it acts as a network that provides information related to opportunities in the market, provides credit for business and acts as a risk

absorber. “In the case of traditional white-collar castes like Brahmins, it provides access to information on new areas of study to help in job opportunities; this could come from extended family networks and, in the current context, even the internet” (Vaidyanathan 2019)

III Brief Review of Literature

Goldar (1985,) Goldar (1988), Bhavani (1991) Tendulkar and Bhavani (1997) have studied the MSME sector to a great extent (Deshpande and Sharma 2016). There has been limited exploration of the MSME sector concerning India’s social structure or from the perspective of marginalized groups like SCs, STs. These social groups work as social capital in the market, which is an essential determinant of the growth of enterprises. A national picture was generated regarding the share of marginalized sections in ownership of private firms under various rounds of national sample survey reports and economic census. But from the viewpoint of marginalized communities, their contribution to output and problems faced by these communities is ignored. Some studies, for instance, Vaidyanathan (2019), Thorat and Sadana (2009), Coad and Tamvada (2012), Iyer, et. al. (2013), Deshpande and Sharma (2013, 2016), Prakash (2018) have studied the share of SCs, STs in ownership of private enterprises at the national level, problems faced by these enterprises, the percentage of these enterprises in workforce employed, growth of these enterprises, etc.

Thorat and Sadana (2009) demonstrated the inter-caste disparity in ownership of private firms and the concentration of enterprises owned by marginal sections in rural areas. They argued that “Age-old restrictions on access to capital by certain social groups reflect themselves in the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes owning far fewer private enterprises than warranted by their share in population, in both rural and urban India”. Data from the fifth Economic Census and NSS Consumption Survey 2011-2012 showed that poverty rates among the enterprises owned by marginalized sections are much higher than other social groups. They point out that a high concentration of household enterprises (Own account enterprises) that work only for subsistence is the leading cause of high poverty. By using various rounds of MSME censuses, Deshpande and Sharma (2013) showed that the share of SCs and STs-owned enterprises declined from 2001-2006; these enterprises are smaller in size, more concentrated in rural areas, the proportion of SC-ST employees is highest in SC-ST owned enterprises and lower in enterprises owned by other caste groups. In an extensive case study in Northwest India, Jodhka (2010) concluded that Dalit businesses face various types of discrimination, which put barriers to the growth of these firms.

Deshpande and Ramachandran (2016) created 10-year cohorts within National Sample Survey (NSS) data, using data from the 55th round (1999-2000) and the 68th round (2011-2012) of the Employment and Unemployment survey to investigate whether disparities are declining or not. A large part of the wage gap is due to unexplained factors caused by discrimination. In 2011-2012 as much as

44 per cent of the wage gap between others and OBCs, and 32 per cent of the wage gap between others and SC-STs is there due to unexplained factors and could be attributed to labour market discrimination (Deshpande and Ramchandran 2016).

Using the Economic Census (2005-2006), Harriss-White, et. al. (2014) created a state-wise all-India atlas of enterprises owned by SCs. They classify India into five regions- Northern region, Southern region, North-eastern region, Central-Eastern region and Western region and then present a brief atlas which shows the SC’s share in different occupations.

IV Caste and Enterprise Ownership- Recent Trends

Economic Census data showed widespread inter-caste disparities in ownership of enterprises using various rounds of the Economic Census. According to the sixth Economic Census 2015-2016, there are 58.50 million establishments in India. Of these, 59.48 per cent are in rural areas, and 40.52 per cent are in urban areas. Among these establishments, 77.55 per cent are engaged in non-agricultural activities and the rest in agricultural and related activities.

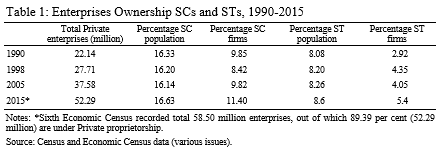

Of the total 58 million establishments, SCs owned 11.4 per cent (12.7 per cent in rural, 9.8 per cent in urban) of the total non-agricultural establishments. They employed about 10 per cent of the total workforce engaged in these activities (Table 1). ST owners owned 5.4 per cent of total establishments and employed roughly five per cent of the total workforce. On the other hand, other social group owners (non-SC/ST/OBC) owned 42.4 per cent of total establishments and employed 47.1 per cent of the total workforce. OBC owners owned 40.8 per cent of total establishments and employed 37.9 per cent of the total workforce in this sector. This data clearly shows that SC and ST have disproportionately less share in enterprise ownership than their share in the population.

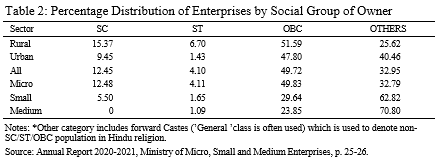

Apart from the Sixth Economic Census 2015-2016, the NSS 73rd round (NSS survey on operational characteristics of unincorporated non-agricultural enterprises, 2015-2016) is also one of the latest available databases on MSMEs. Table 2 shows the distribution of enterprises by the social group of owners in rural and urban areas and in the enterprise category as per NSS 73rd round 2015-2016.

While SCs, STs owned enterprises are concentrated more in rural areas, on the contrary, other owned enterprises are concentrated more in urban areas (Table 2). The transition from micro to small to medium indicates the persistent growth of enterprises. The missing middle is an important challenge in the MSME sector in India, but Table 2 shows that the small sector is also missing in SCs, STs owned establishments. Almost all of the SCs, STs owned enterprises are micro- enterprises. These establishments have a negligible 5.5 per cent share in small enterprises, and not even one was in the medium category.

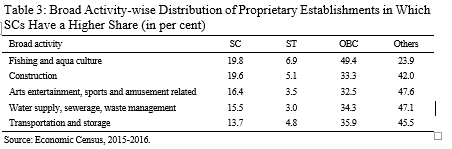

Data from the last four economic censuses indicates a growing representation of SCs in the ownership of enterprises, but a close look at the data shows inter- caste disparities. The broad activity status for different social groups indicates that SCs owned enterprises have a higher share in construction (19.6 per cent), fishing and aquaculture (19.8 per cent), water supply, sewerage and waste management (15.5 per cent), arts and sports-related enterprises (16.4 per cent) (Table 3). Most of these occupations require less education, skill, and capital and require more manual labour.

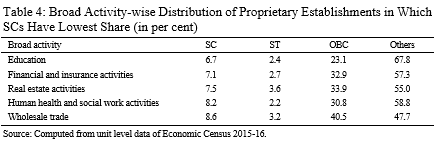

Historically SCs face restrictions of access to education, professional skills, ownership of productive assets such as land and capital etc. Due to discriminatory attitudes towards SCs in these areas, their representation in establishments in these categories is much less than their share in the population (Table 4). For example, of the 7.5 lakh establishments in the education category, only 6.7 per cent are

owned by SCs; while 67.8 per cent of enterprises are owned by other social group (non-SC/ST/OBC). In the real estate category, SCs shares 7.5 per cent of the total

4.1 lakh establishments, contrary to 55 per cent shared by other social groups. In health and social work activity, out of 6.8 lakh establishments, 8.2 per cent are owned by SCs and 58.8 per cent are owned by others.

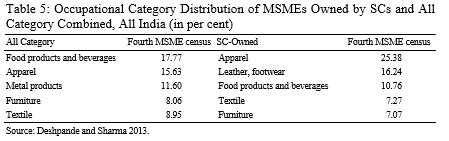

Most SCs owned enterprises are engaged in traditional caste-based occupations such as leather tanning, footwear, sanitation-related activities, scrap business etc. (Deshpande and Sharma 2013). They have less participation in some occupations, which are among the top activities for other social groups such as food and Beverages, metal products, furniture, textiles, etc. (Table 5). Many SC- owned enterprises in food and beverages segments have adopted some names of shops which characterized them as upper castes, for example, Balaji Misthan Bhandar, Bhavani sweets corner, etc. “The stigma of untouchability has traditionally kept Dalits out of food-related industries” (Navsarjan Trust 2010, Shah, et. al. 2006).

SCs, STs owned enterprises have not yet emerged as job givers; most of these enterprises are survivalists. Deshpande and Sharma (2013) stated, “Entrepreneurship as a vehicle for social mobility for Dalits is yet to become a reality for India”. Among SC/ST-owned enterprises, employee share

(Establishments) is higher in rural enterprises, but among other social group- owned enterprises, the share of employment is higher in Urban enterprises.

SCs shared 16.4 per cent of the population in 2011; but they owned 9.8 per cent of all enterprises in 2005, which employed eight per cent of all non-farm workers. STs share 7.7 per cent of the population but own only 3.7 per cent of non- farm enterprises and employ 3.4 per cent of the workforce. On the other hand, the share of OBC in enterprise ownership and workforce roughly corresponds with their share in the population; other social group has a much higher share in enterprise ownership than their share in the population (Iyer, et. al. 2013). MSME census data showed that only four per cent of the total workforce is employed in SC-owned enterprises, 2.2 per cent in ST-owned enterprises, 27 per cent in OBC- owned enterprises, and 66 per cent in other social group-owned enterprises (Deshpande and Sharma 2013).

If we analyze the pattern of the structure of employees, we can see a distinct pattern. The percentage of SC employees in SC-owned enterprises is declining, while the proportions of employees from other social groups in enterprises owned by those respective groups are increasing. According to the MSME census, 2001- 2002 and 2006-2007, the share of SC employees in SC-owned enterprises declined from 85 to 61 per cent, while among other-owned enterprises, 77 per cent of employees belong to the owner social group (Deshpande and Sharma 2013).

Of the total workforce employed in this sector, 10 per cent were employed in SC-owned establishments, which is less than their share in establishment ownership and population. The highest numbers of workers were employed in other social group-owned firms. Other social groups that constitute historically forward castes are the only category with a higher share in employment compared to their share in ownership of firms.

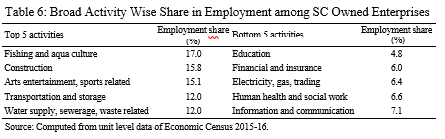

Data shows apparent inter-caste disparity if we further stratify overall employment into different activity categories. SC-owned enterprises have a much higher employment share in low-paid activities such as fishing and aquaculture, construction, arts, entertainment, transport and storage, water supply, sewerage, waste management, etc. Within higher-earning sectors such as education, financial services, health and social work, information and communication, and more, SC- owned enterprises possess a significantly lesser market share (Table 6).

Firms owned by SCs and STs are smaller in size than those of other social group-owned firms. The average size is 2.73 for enterprises owned by non-SC/ST owners, 1.72 for SCs and 1.89 for STs (Iyer, et. al. 2013). For firms with more than three employees (medium number of employees in manufacturing MSMEs- MSME census 2006-2007), 70 per cent of the employees in other-owned firms are from the same castes, 39 per cent of employees in SC-owned firms are SCs (Deshpande and Sharma 2013).

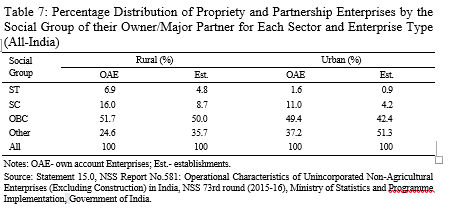

The size of an enterprise is an important indicator of the enterprise scale as it clearly shows the entrepreneurial tendency of enterprises. National Commission on Enterprises in the unorganised sector (2008) showed that SC-ST-owned enterprises are more informal and have low productivity. Own account enterprises (OAE) are those that run without any hired worker or are small enterprises that depend on family labour. Establishments are enterprises that work with at least one hired worker. SCs, STs and OBCs have a relatively high share in OAE and a relatively low share in establishments. In the case of SC-owned enterprises, out of total 12.4 per cent share, 13.8 per cent were OAE, and 5.5 per cent were establishments for STs, out of a total 4.1 per cent share, 4.5 per cent are OAE, and two per cent are establishments. Among other social group-owned enterprises, out of a total 32.9 per cent share, 30.3 per cent were OAE, and 47 per cent were establishments (NSS 73 round 2015-2016). Thus SC-STs have a higher share in OAE, while other social groups have a higher share in establishments (Vaidyanathan 2019). Self-employed individuals or Owner operated units are more survivalist in nature than entrepreneurship tendencies. Thus the proportion of owner-operated enterprises is highest among SCs and lowest among other category.

In urban areas, the disparity is much higher among social groups (Table 2 and Table 7). In urban areas, enterprises owned by SCs, and STs have a higher share in rural areas and Own account enterprises (OAE-single-headed proprietary

enterprises). In establishments that worked with hired labour, the share of SC-ST- owned enterprises is much less than their share in the population (Table 7). As per the 73rd round of NSS data, SC-owned enterprises account for 12.45 per cent of the total; however, their ownership share is higher in rural regions (15.37 per cent), particularly within the realm of own account enterprises (16 per cent) in rural areas. They have a lower share in urban areas (9.45 per cent) and a lower share in urban establishments (4.2 per cent). Self-employed individuals manage these own account enterprises, these are survivalist in nature and are susceptible to economic shocks.

A recent survey by the Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises showed that 12.45 per cent of the total unregistered non-agriculture MSMEs were owned by scheduled castes, but not even one was a medium-sized MSME. This indicates that most enterprises owned by Dalits (SCs) are only self-employed individuals depending on family labour and family resources. SCs and STs have lower participation in business ownership relative to their share in the population; the proportions of these businesses were higher in rural areas (Annual report 2020- 2021, Ministry of MSME)

VI Discussion

In economic literature, theories of discrimination can be divided into two heads named as ‘Theory of Statistical Discrimination’ by Arrow (1971), Phelps (1972), Akerlof (1984) and ‘Theory of taste for discrimination’ given by Becker (1957), etc. The theory of Statistical Discrimination argues that rational economic agents discriminate due to imperfect information. These theories violate the assumption of perfect information and say that agents do not pay according to their marginal productivity but are paid according to their group identities. Employers do not have perfect information about employees; thus, identity works as an indicator of quality in statistical discrimination theories (Arrow 1971, Akerlof 1984). Another side of economic theories comes under the ‘Theory of Taste for Discrimination’. One of the famous economists of this approach, Becker (1957), said that an individual could discriminate inspired by his ‘Taste for discrimination’. Becker pointed out that individuals can discriminate without objectively considering facts such as quality or efficiency. He claimed that individuals could discriminate even at the cost of efficiency or profit. Pre-market and Market Discrimination led unfavourable outcomes for SC-ST entrepreneurs, as explained by the theory of taste for discrimination.

Institutional Economics describes that social-cultural and economic institutions affect economic growth and development. The caste system works as an institution in India and impacts the economy. It plays a vital role in shaping economic opportunities for individuals. The fact is substantiated by the higher share of Dalits (SCs) in wage labourers, casual labourers, sanitary workers, and carcass cleaners, along with their relatively lower representation in well-paying

positions. The persistent wage gap among social groups and higher poverty rates among SCs/STs confirm this reality.

Caste still works as an important indicator of socio-economic outcomes in India. Dalit caste networks are weak; they have less capital; thus, they see the state as a balancing institution. However, due to historical legacy and relatively more social and economic capital, upper castes benefit more from the state, reproducing the caste and class character in markets. Indian markets are not perfectly competitive; thus, caste identity works as an institution that affects market outcomes. “Caste networks suppress competition by protecting market shares, creating adverse conditions for Dalits in the factor and product markets” (Harriss- White 2014, p. 19).

SCs and STs face difficulty obtaining initial formal credit; they get informal credit at much higher rates. It is reported that sometimes they get lesser prices for their goods and services, or sometimes they are forced to sell at lower prices due to the discriminatory attitude of consumers (Jodhka 2010). Residential segregation is an essential result of the caste system in India. We can see separate Scheduled caste colonies in most of the states. Geographical segregation limits the market for SCs and STs entrepreneurs. Due to the high incidence of poverty among SCs and STs, they may have to charge lower prices for their goods and services. Dalit colonies have poor infrastructure facilities such as poor education, health, roads, and other municipal facilities, limiting economic opportunities for Dalits. Prakash (2018), in his empirical study of 90 SC entrepreneurs, concluded that the “market is mediated and influenced by social structures and social contexts in which the economic agents live”.

MSMEs need both working capital as well as long-term capital. A large share of them depends on credit through social networks, their savings, and the sale of their assets. Dalit entrepreneurs have fewer assets due to their historical legacy; thus, they face more problems accessing formal credit. Dalits get little credit from other castes or obtain credit at higher rates because other castes think that businesses owned by dalits may not yield substantial profits. Caste plays a significant role in the growth of enterprises; SC-owned enterprises recorded lower growth, and these enterprises are survivalist.

Weber’s Theory of Industrial location states that the place of the business and industries is essential to business success (Weber 1929). Other castes have a significant presence in the market; they do not want to share places with new business entrants such as dalits and tribals. While certain states have implemented policies to allocate market space for Dalits, a closer examination reveals that these individuals have been assigned shops in less advantageous locations, with smaller shops designated for them.

The government has initiated policies such as public procurement from SC- ST-owned establishments, priority sector lending to weaker sections of society, stand-up schemes, etc. The central government as well as the state government have initiated various policies for the betterment of Dalits in business; but due to inefficient implementation, these policies are not very effective in outcomes. For

example, in the stand-up India scheme, banks have been mandated to give loans between ₹10 Lakh and ₹1 Crore to at least one Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe borrower and at least one woman borrower per bank branch for setting up a greenfield enterprise. Data on various beneficiaries under Stand Up India Scheme (2019-2021) shows that 80 per cent of the loan goes to women, 13.8 per cent to SCs, and 5.7 per cent to STs.1

While SCs are under-represented in upper echelons of government, on the other hand, SCs have disproportionate higher representation at clerical posts and group D level posts, safai karamcharis. Upper echelons of government and some departments such as police, commercial tax department, electricity board and municipalities govern most aspects of businesses licenses, site allocation, infrastructure facilities, logistics facilities etc. It is often seen that SCs have less representation in the upper echelons of these departments, which leads to the unfavourable exclusion of SCs in business. Lack of early-stage Risk capital, Inexperience in deploying credit and capital, lack of organizational capability, Inability to deploy Managerial talent, etc., are important challenges faced by SCs entrepreneurs (Mehrotra, et. al. 2020).

In the last two decades, a few Dalit businessmen became billionaires, which gave rise to debate on ‘Dalit capitalism’. Chandrabhan Prasad, a member of the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DICCI), argued that dalits should be the owner of capital, Dalits should become Entrepreneurs, and they should become Job givers. Contrary to that, Gopal Guru and Anand Teltumbde argued that in the new dalit capital, members remain subordinate to politicians and the state; a few members of the dalit community became billionaires, but the ‘spectacle of the few’ masks the neglect of the many (Guru 2012, Teltumbde 2011).

Thus we need to think deeper about the factors responsible for the disparity in ownership of firms and the growth of these enterprises. These factors include social capital, networks, unfavourable exclusion or unfavourable inclusion, discrimination in the factor market or product market, etc. A more comprehensive analysis needs to be conducted at various levels, including the state, local, and occupation levels, to understand the role of social capital as trust, network effects etc. and the determinants of growth of entrepreneurship in India.

VII Policy Implications

Dr B.R. Ambedkar said in a speech – “We want industrialisation of India as the surest means to rescue the people from the eternal cycle of poverty in which they are caught. Industrialisation of India must, therefore, be grappled with immediately” (Ambedkar 1990). Dalit youths have to acquire the required skill, innovative mindset and entrepreneurial spirit so that they can play a more significant role in businesses.

Some historical examples show us that business ownership and asset ownership have a significant positive correlation with social mobility: the economic progress of ethnic minorities in the US, the economic progress of ethnic

minorities in Malaysia and South Africa, etc. Indian society is structured in a hierarchal social order based on caste, gender, etc. Historically marginalised sections such as SC-STs have experienced lower status in most spheres of life. Even now, dalits, the most underprivileged sections of society, are at the bottom in various economic indicators such as business ownership, asset ownership, education-health-related indicators, consumption expenditure etc.

Since independence, we have had affirmative action policies in education, jobs, legislature, etc., but the government has never adopted a proactive approach in the field of fair market participation or equitable asset ownership in the market for historically deprived sections. Liberalisation -Privatisation- Globalisation has changed the employment scenario in India; it also affects the government’s job opportunities. Hence it drastically reduced reserved jobs for marginalised sections. Therefore, Business ownership and fair market participation can play a vital role in the upward social mobility of marginalised sections.

Some countries implemented direct affirmative action policies to address the disparity in business ownership, such as the Malaysian affirmative action programme, which reserved 30 per cent of all business ownership for ethnic Malays and the South-African policy of Black Economic Empowerment to redress the inequalities of Apartheid, etc. The public procurement policy of the Government of India is a progressive step in this direction. The affirmative action policy should not only focus on increasing participation but also on improving business performance because business failure can discourage first-generation dalit entrepreneurs and make them homeless.

Endnote

1. https://static.pib.gov.in/WriteReadData/specificdocs/documents/2021/nov/doc2021113061.pdf

References

Akerlof, G. (1984), The Economics of Caste and of the Rat Race and Other Woeful Tales, An Economic Theorist’s Book of Tales, pp. 23–44, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ambedkar, B.R. (1943), Post-war Development of Electric Power in India, Presidential Address in the Second Meeting of Policy Committee in Delhi, Indian Information, 15 November 1943,

pp. 125–128.

———– (1990), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 7, Government of Maharashtra, Bombay, 243.

———– (1990), Annihilation of Caste: An Undelivered Speech, Arnold Publishers, New Delhi.

Bayly, S. (1999), Caste, Society and Politics in India: From the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age, Cambridge University Press.

Becker, G. (1957), The Economics of Discrimination, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Clark, K. and S. Drinkwater (2000), Pushed Out or Pulled in? Self-Employment among Ethnic Minorities in England and Wales, Labour Economics, 7(5): 603-628.

Damodaran, H. (2008), India’s New Capitalists: Caste, Business and Industry in a Modern Nation, Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Desai, S. and A. Dubey (2011), Caste in 21st Century India: Competing Narratives, Economic and Political Weekly, XLVI(11): 40–49.

Deshpande, A. (2000), Does Caste Still Define Disparity: A Look at Inequality in Kerala, India,

American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 90(2): 322–325.

———– (2011), The Grammar of Caste: Economic Discrimination in Contemporary India, New

Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Deshpande, A. and S. Sharma (2013), Entrepreneurship or Survival? Caste and Gender of Small Business in India, Economic and Political Weekly, XLVIII(28): 38–49.

———- (2015), Disadvantage and Discrimination in Self-Employment: Caste Gaps in Earnings in

Indian Small Businesses, Small Bus Econ (46): 325–346, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015- 9687-4

Fukuyama, F. (1996), Trust: The Social Virtues and The Creation of Prosperity, Simon and Schuster. Government of India (1991, 2001, 2011), Economic Censuses, Ministry of Statistics and Programme

Implementation.

———- (2007), MSMEs Census, Ministry of Micro Small and Medium Enterprises.

———- (2007), Report on Conditions of Work and Promotion of Livelihoods in the Unorganised

Sector, National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector 2007.

———- (2012-13), Report on Employment in Informal Sector and Conditions of Informal Employment (2013-14), Labour Bureau, Chandigarh, Ministry of labour and Employment.

———- (2015), Strategy for New India @75, NITI Aayog.

———– (2016), All-India Report of Sixth Economic Census 2015-16, Ministry of Statistics and

Programme Implementation.

———- (2021), Periodic Labour Force Survey, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, New Delhi.

Guru, G. (2012), Rise of the ‘Dalit Millionaire’: A Low Intensity Spectacle, Economic and Political Weekly, 47(50): 41-49.

Guru, G. (Ed.) (2009), Humiliation: Claims and Context, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Harriss-White B., E. Basile, et. al. (2014), Dalit and Adivasis in India’s Business Economy: Three

Essays and an Atlas, Haryana: Three Essays Collective.

Harriss-White, B., S. Janakarajan, et. al. (2004), Rural India Facing the 21st Century, London: Anthem.

Hnatkovska, V., A. Lahiri and S. Paul (2011), Breaking the Caste Barrier: Inter-Generational Mobility in India, faculty.arts.ubc.ca/vhnatkovska/Research/Intergeneration.pdf.

Iyer, L., T. Khanna and A. Varshney (2013), Caste and Entrepreneurship in India, Economic and Political Weekly, XLVIII(6): 52–60.

Jodhka, S. (2010), Dalits in Business: Self-Employed Scheduled Castes in Northwest India, Indian Institute of Dalit Studies Working Paper, 4(2).

Kapur, D., C.B. Prasad, L. Pritchett and D.S. Babu (2010), Rethinking Inequality: Dalits in Uttar Pradesh in the Market Reform Era, Economic and Political Weekly, 45(25): 39-49.

Madheswaran, S. and P. Attewell (2007), Caste Discrimination in the Indian Urban Labour Market: Evidence from the National Sample Survey, Economic and political Weekly, 42(41): 4146-4153.

Mehrotra, S. (2018), The Indian Labour Market: A Fallacy, Two Looming Crises and a Silent Tragedy, Centre for Sustainable Employment Working Paper #9, Azim Premji University, Bangalore.

———- (2020), Reviving Jobs: An Agenda for Growth, Penguin Random House India Private Limited.

Munshi, K. and M. Rosenzweig (2009), Why is Mobility in India So Low? Social Insurance, Inequality, and Growth, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 14850.

Murphy, C. (2006), The Power of Caste Identity in Private Enterprises Ownership, MSc Thesis in Economics for Development, Oxford University.

NSSO (2015-16), 73rd Round Unincorporated Non-Agricultural Enterprises (Excluding Construction) Survey, 2015-16.

Prakash, A. (2018), Dalit Capital and Markets: A Case of Unfavourable Inclusion, Journal of Social Inclusion Studies, 4(1): 51-61.

Putnam, Robert D. (1994), Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy, Princeton University Press.

Rodrigues, V. (2019), The Essential Writings of BR Ambedkar, Oxford.

Saxena, S. (2011), Caste and Capital Can’t Coexist, Interview with Milind Kamble, Times of India, 2 October.

Srinivas, M.N. (1966), Social Change in Modern India, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Swaminathan, S. Aiyar (2000), Social Capital—An Idea Whose Time Has Come, The Times of India, 28 May.

Teltumbde, A. (2011), Dalit Capitalism and Pseudo Dalitism, Economic and Political Weekly, 46(10): 10-11.

Thorat, S. and K. Newman (Eds.) (2010), Blocked by Caste: Economic Discrimination in Modern India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Thorat, S. and K.S. Neuman (2012), Blocked by Caste: Economic Discrimination in Modern India, Oxford University Press.

Thorat, S., S. Madheswaran and B.P. Vani (2021), Caste and Labour Market: Employment Discrimination and Its Impact on Poverty, Economic and Political Weekly, 56(21): 55-61.

Vaidyanathan, R. (2019), Caste as Social Capital, Penguin Random House India, New Delhi.

Weber, A. and C.J. Friedrich (1929), Alfred Weber’s Theory of the Location of Industries, University of Chicago Press.