Gendered Patterns of Unpaid Care Work Distribution in India: An Empirical Exploration from First Large Scale Time Use Survey 2019

September 2023 | Dakrushi Sahu

I Introduction

Feminist economists have long argued to broaden the scope of economics to encompass the unpaid work performed in the domestic sphere. The Marxist feminists, during the 1970s, emphasized the problems of unpaid care work, referring it to ‘housework’, ‘domestic labour’, or ‘reproductive labour’ (Berik and Konger 2021, p. 6). Their critical argument was that women primarily serve men within the household as well as sustain the capitalist economy through their reproductive role (Hartmann 1979, pp. 1-33). It is worth noting that the strand of Marxist feminist scholarships, by the end of the 1980s, was subsided, and hence, the explanation of women’s oppression at the domestic space owing to the labour theory of value remained overlooked. However, the role of unpaid care work remained at the forefront of discussion in academic scholarship.

One crucial debate that went on amongst feminist economists was whether unpaid care activities fall within the domain of “work” or not. Margaret Reid (1934) pioneered developing the theories and methodologies for consumption within the domestic spheres. Her third-party criterion suggests that unpaid care can be treated as “work” since caring activities like child care, elder care, cooking, cleaning, etc., can be delegated to a third person.

Dakrushi Sahu, Senior Research Fellow (Ph.D.), Centre for Informal Sector and Labour Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 110067, Email: dakrushisahu@gmail.com

The definition of care work has evolved and broadened over time. Attempts have been made to “delineate it from the category of domestic labour” (Moos 2021, p. 90). Himmelweit (1995, p. 9) defines care work considering the relationship between a carer and her work. It is similar to the definition provided by Folbre (2018a)- she calls it “direct care work” which requires a high degree of intimate, personal, or direct relationship between a caregiver and a care receiver (as in the case of child care per se). The term “indirect care work”, on the other hand, refers to work that requires less personal or intimate engagement between the caregiver and care receiver, for instance, cooking, cleaning, laundry, etc. (Folbre 2018b). Folbre’s typology also includes a third category called “supervisory care” or “passive care1”- supervision of children or any other dependent adults while performing other household tasks simultaneously. Hence, unpaid care work is a broader term that encompasses both direct and indirect unpaid care work, on the other hand, household labour which is termed as “housework” includes only indirect care work (Moos 2021, p. 91).

II The Domestic Labour Debate (DLD): An Overview

The framework of the Marxist political economy has provided wide-ranging insights on theorizing human subordination under capitalism. Women’s unremunerated activities at the domestic space-often called “domestic labour” or “unpaid care work” or “unpaid household tasks” are no exception. The framework has provided a ground for a materialist analysis of women’s oppression since the late 1960s.

The value of the commodities bought from the market is transferred, through domestic labour, to the end-product called “labor power” (Hensman 2011, p. 7). However, the question arises- does the household labour produce value? The answer is a big “yes” because domestic labour contributes to the production and reproduction of labor-power which is, like any other commodities, sold in the labour market (op. cit., p. 7). Although domestic labour does not produce exchange value, it produces use value. Substantial components of it contribute to the consumption basket of all the household members (Himmelweit and Mohun 1977,

p. 16). Regular and continuous individual consumption is required to maintain labour power. This is mainly because the labour power- the ability to work is used up every day and thus, ceases to exist over time (if an individual stops consuming domestic services continuously).

It is worth noting down that labour power of a particular person (labourer) does not remain eternal. As they (labourers) grow older and die, society’s stock of labour power changes. Hence, the birth of children-reproduction of the human species becomes inevitably necessary for reproducing the labour power continually (op. cit., p. 16) and sustaining the capitalist economy.

One crucial aspect, then to observe, is whether domestic labour produces surplus value or not. Domestic labour, performed by a housewife per se, does not receive any wage directly from the market. But she is remunerated (more or less)-

most often, in terms of kind,out of her husband’s wage obtained from the employer. Hence, a housewife is indirectly paid by her husband’s employer (capitalist) for the domestic services she performs. She wouldn’t be producing any surplus value if her husband pays her equal to or more than the value of domestic services provided in the market. On the other hand, if she is paid less than the value of her services by her husband’s employer, then the employer is not paying part of the wages. These unpaid wages add up to his (employer’s) surplus value (Hensman 2011, p. 8). The processes through which the surplus value arises, give rise to a model of unequal exchange- “first, between capitalist and worker, over the purchase and sale of labour-power and second, between husband and wife, over the exchange of her labour-time for part of the commodities bought with his wage” (Himmelweit and Muhun 1977, p. 24). In this way, a housewife’s unpaid domestic labour indirectly produces surplus value.

When time spent on domestic labour is extended unduly, the reproductive labour produces an extra-surplus value which is appropriated by the capitalist (Hensman 2011, p. 8). This appropriation becomes possible by exploiting the women in the domestic space and subsidizing the production of labor-power. It is worth noting here the comparison made between the value of unpaid domestic services carried out at home and the value of the same services transacted in the market. Domitila Barrios de Chungara- the Bolivian women’s leader and miner’s wife opines that “One day I got the idea of making a chart. We put as an example the price of washing clothes per dozen pieces and we figured out how many dozens of items we washed per month. Then the cook’s wage, the babysitter’s, the servant’s. . . Adding it all up, the wage needed to pay us for what we do in the home . . . was much higher than what the men earned in the mine for a month2” (Hensman 2011, p. 9).

Interestingly, the “indirect care work” can easily be mechanized and thus, its burden can be reduced3 (Hensman 2011, p. 16). On the other hand, “direct care work” can’t be mechanized. This is mainly because caring and nurturing activities are labour intensive and encompass affective and cognitive elements (op. cit., p.16). One simple way through which the burden of unpaid household tasks can be reduced is the mechanization of the work formerly performed manually. The process has already started and reached a great height in the first world countries, but the same is not true for the countries like India. For instance, the use of refrigerators can reduce the amount of time spent on shopping and cooking and is common amongst the upper strata of society. However, millions of poor households, who are living in rural areas and urban slums, can’t use it as they can’t afford it. Most regions also lack infrastructural facilities like power supply. Women in these regions bear an enormous amount of unpaid household tasks as they spend the most time fetching water, collecting firewood, and so on. Reproduction of labor-power also gets undermined as women succumb to deterioration in health which results from smoke (while cooking with firewood, they suffer from respiratory diseases), poor sanitation facilities (results in water- borne diseases), etc. Hence, the state must intervene to facilitate the reproduction

of labor-power, and reduce the unpaid work burden on women. The provisioning of “subsidized housing, electricity, potable running water, sanitation, and solar- powered stoves” can reduce the domestic work burden on women. In this respect, Maxine Molyneux (1979) suggests adopting practical measures such as “elimination of gender division of labour in employment, equal sharing of domestic labour between men and women, provision of crèches and nurseries for all children whose parents need childcare and sheltered accommodation or home- care for adults who need it, shorter working hours, and regular part-time jobs, flexible working hours to suit the needs of the employees – for both men and women who have caring responsibilities” (Molyneux 1979, p. 27).

As Folbre (2017) argues, care services are, most often, offered with the hope of mutual benefit- with an expectation of payback, or a promise of remuneration. This can take place either in a formal or informal exchange process. Unpaid care services, in household settings, are provided through an informal exchange process (Folbre 2017, p. 751) and thus, freedom to entry or exit is greatly hindered, unlike participation in a competitive market where participants enjoy the freedom to entry and exit and confront a large number of consumers and producers. However, in a family, members are morally and legally obliged to each other. Still, adult male members of the family exit from the commitments since their work involves less emotional attachment. However, women, in the family, get strongly attached to younger children while providing care services per se, and hence, they can’t exit easily from the commitment. Interest to provide care services also arises out of altruistic motives and thus, the caregivers are concerned about “fostering the well- being of care recipients compromising their subjective happiness” (op. cit.).

Paula England (2005, pp. 381-399) discusses five emerging theories of care work (both paid and unpaid). These five theoretical frameworks provide competing answers to the same question and also distinct answers at different times. The theories are vital for understanding the mechanisms of care work in an economy. They have been discussed as follows;

Devaluation theory illustrates that care work is underpaid or unpaid because this work refers to female-identified occupations. The gender pay gap arises in the paid labour market mainly because men and women are engaged in different jobs (Petersen and Morgan 1995, pp. 329-365). The differential payment to men and women for the same job hardly prevails in the contemporary world. Female- identified jobs are paid lesser than male-oriented jobs after “adjusting for measurable differences in educational requirements, skill levels, and working conditions (Steinberge 2001, pp. 2393-2397). The devaluation theory can be applied to both race and gender (England 2005, p. 384). For instance, paid care work requires a certain level of educational degree which is met and performed by white women (in the context of western countries). On the other hand, women of colour perform paid care work without having such a degree, and hence, they receive the lowest remuneration from the market.

The public good framework explains that care jobs have both implicit and explicit benefits within an economy and thus market fails to reward care work.

This theory, therefore, suggests state intervention for efficient market equilibrium. Care work, both paid or unpaid, improves the capabilities-intellectual, physical, and emotional, of its receivers. They (care receivers) develop skills-including cognitive skills that enhance the earning capacities, values, and habits which benefit themselves as well as spillovers to others. The benefits received directly from the caregivers also benefit indirect recipients. But how did this happen? One obvious example is education. A teacher (paid caregiver) provides education to his/her students (care receivers). After completing the term of education, students benefit themselves by becoming able to earn from the market and also benefit employers, society with educative values, and their family members. The spill- overs or the externalities that accrue to the indirect recipients make the care work arguably a public good (op. cit., p. 385). Dolla Costa and James (1972, pp. 79-86) pointed out that Marxist feminists’ argument in this regard was quite similar but narrower. They critically viewed that women are exploited by the capitalists as their caretaking responsibilities make, their husbands and the next generation, productive and they (women) do not receive a wage from the market equivalent to their value of labour. Hence, capitalists accrue surplus value by exploiting both homemakers and paid workers. However, the advocates of the framework of the public good go beyond the idea of Marxist feminists. According to them, indirect benefits accrued from care work do not merely benefit the capitalists, but all the persons in an economy. “The extent to which benefits of caring labor will go beyond the direct beneficiary to others depends, in part, on how altruistic the beneficiary is—which is often a function of the kind of care she or he received” (England 2005, p. 386).

The term “prisoners of love” was coined by Folbre (2001). ‘Prisoners of Love’ phenomenon describes that individuals involved in care jobs become more caring (emotionally attached). Because of the emotional bonding that occurs between caregivers and care recipients, the former hesitate to demand more wages from the market for their service. They do not demand any wages when the task is performed at the household level where the degree of emotional bonding remains to be quite high. Hence, employers pay less to the caregivers taking advantage of their intrinsic caring motives in the market and husbands underpay or often do not pay them in the household.

Hochschild (1983) pioneered the ideas behind the commodification of emotion coining the term “emotional labour” in her seminal work “The Managed Heart”. Her study pointed out that the provisioning of care services through the market harms the caregivers. Many jobs require caregivers to show positive feelings even when they do not feel so (feeling is not natural). For instance, flight attendants need to be cheerful even when they are sad. As per Hochschild, this deep emotional acting leads to psychological distress (England 2005, p. 391). She has viewed that care work is more alienating than other kinds of work. Many women, as well as men, clean houses or work in factories and restaurants. They even migrate to other countries, leaving their children and other care-dependent persons in the households, in search of a better livelihood and work as nannies.

She remarks, drawing insights from Marx, that selling one’s heart (emotional labour or caring labour) is always alienating and exploitative. It is worse when employers of one country demand laborers of other countries for care work (op. cit., p. 392).

The theory behind “love and money”, proposed by Nelson (1999, 2004) and Zelizer (2002a, b), rejects the idea of an “oppositional dichotomy between the realms of love and self-interested economic action”. Since men and women are viewed as the opposite, and a tacit assumption is made about gender, a dualistic view emerges: “Women, love, altruism, and the family are, as a group, radically separate and opposite from men, self-interested rationality, work, and market exchange” (Nelson and England 2002, pp. 1-18). As per Zelizer (2002a), this oppositional dualism is nothing but the view of a “hostile world”. Self-interested economic action and profit motives rule the market. Thus, markets are antithetical to genuine care. On the other hand, caring values rule the families, non-profit, and governmental organizations. “Love and Money” perspective, hence, argues that genuine care can be found in families, communities, non-profit organizations, and state actions. Therefore, the theory suggests that care provisioning should, ideally, not operate through market mechanisms.

Kabeer’s (2021, p. 99) consideration of the concept of capabilities and their contribution to livelihood is commendable. Capabilities mirror out the interaction between the resources and abilities to translate them into valued goals. Patriarchal structure, during the contemporary period, constrains women’s capabilities in comparison to that of men worldwide. Although the constraints vary across the countries, they depict some sort of commonalities. For instance, a grave inequality persists in the distribution of critical resources between men and women. The gendered division of labour, owing to social norms, allocates a disproportionate share of unpaid reproductive responsibilities to women in the household domain (op. cit., p. 100). As a result of which women tend to curtail their opportunities to participate in the economic and political spheres. The hegemonic gendered ideologies view women as inferior to men (women as lesser capable than men) and undermine their sense of “self and social worth”.

The contemporary social reproduction theory (SRT) could be regarded as the carrier of the legacy left by domestic labour debates (Moos 2021, p. 92). Bhattacharya (2017, p. 1), in her introductory remarks to an edited volume on Social Reproduction Theory, questions that “If workers’ labour produces all the wealth in society, who then produces the workers?” Notably, this question is central to the theory of social reproduction. From a Marxist perspective, human labour drives production and reproduction in an economy. The SRT theory goes beyond the analysis of commodity production and explores the production and reproduction of human life itself. The fundamental idea behind the theory is to locate human labour at the centre of production and reproduction of the society as a whole (op. cit., p. 2).

It has been pointed out that material ingredients required to produce the worker such as “food, housing, or time for education, for intellectual development,

or free play of his (her) own physical and mental powers” (Bhattacharya 2021, p. 76) lies beyond the ambit of recognition within the capitalist production process. This is mainly because capitalists are always oriented towards valorizing capital and are not concerned for the social development of the workers. Hence, workers lack, in a capitalist economy, in what they should ideally possess from social viewpoints. This negligence within the capitalist economy leads to class struggle and provokes the workers to demand wages to compensate for their unfulfilled livelihoods. Social reproduction theory explains this owing to the relationship between “worker’s existence outside the circuit of commodity production” and “productive lives under the direct domination of capitalist” (op. cit., pp. 68-69).

In the contemporary period, unpaid care work is conceptualized from a broader perspective; especially a three-way classification is made (Budlender 2010, ILO 2018). It includes unpaid domestic services, unpaid direct caregiving services, and unpaid volunteer and community services. Such a finer disaggregation helps in exploring the different patterns and replications across the sub-categories of unpaid care work. Neetha and Plariwala (2010, p. 105) found out, employing India’s pilot time use survey 1998-19994, that women spend relatively more time than men across the components of unpaid care work in the country as a whole. But such female-biased gendered patterns don’t hold across the rural and urban regions, while observed individually. Their findings reveal, for instance, that rural men devote a higher amount of time to unpaid care work relative to urban men. Considering all the three components of unpaid care work, they found out that men take the maximum share of unpaid volunteer and community services in rural areas unlike that in urban areas (op. cit.). Men’s unpaid care work typically reflects the “masculine” activities i.e. house-repair per se, especially when their total share of unpaid care work tends to be lower (ILO 2018). Though unpaid care work is indispensable for the survival of human society, most of it goes unrecognized, undervalued, and unaccounted for (Boserup 1970, Bineria 1992). In the case of voluntary work, gender asymmetricity is significantly higher (Bineria 1992, p. 1550).

It is important to empirically examine such nexuses in the contemporary period, especially in the context of a developing country like India. We have done so, considering all the three components of unpaid care work, with the help of India’s first large-scale time use survey-2019.

III Research Questions and Objectives

Scant attention has been paid in the literature, especially in third-world countries, with respect to exploring empirical evidence on the gender-biased distribution of unpaid care work. This is mainly due to the unavailability of nationally representative time-use data. With the help of India’s first large-scale time-use survey data, we have empirically examined the gendered patterns of unpaid care work distribution.

Given the theoretical arguments, we seek to answer the following questions: To what extent do the men and women take a share of unpaid care work in India? And, does the gendered time allocation pattern on unpaid care work vary substantially across its components?

Keeping in mind the above research questions, we have formulated two specific objectives:

(1) To empirically examine the asymmetric distribution of unpaid care work and its components (unpaid domestic services, unpaid direct caregiving services, and unpaid volunteer and community services) between men and women in India.

(2) To unfold the variation in such gender patterns across the rural and urban regions.

IV Data and Key Concepts

The main source of data considered in the study is India’s first large-scale time- use survey conducted by National Statistical Office (NSO) in 2019. The survey is the most recent one and covers the whole country, except for the Andaman and Nicobar Islands5. Data on time use was gathered from the persons who were of age 6 years and above. Since the objective of the survey was to capture time use information on a daily basis, a 24-hour recall interview method was employed with the reference period starting from 4:00 AM on the day before the date of the interview to 4:00 AM on the day of the interview. The sample size was quite large enough: 4,47,250 individuals out of which 2,73,195 individuals were from rural India and 1,74,055 individuals were from urban India.

We have adopted two important measures such as the percentage rate of participation and the average time spent per participant. The percentage rate of participation in an activity refers to the proportion of persons participating daily in that activity. Mathematically, it can be expressed as;

Percentage rate of participation in activity “A”

= Number of Persons Participating in Activity “A” × 100

Total Nuber of persons

Likewise, the average time spent per participant refers to the mean time spent in a day on a particular activity. This can be expressed as follows;

Average time spent per participant= Total Time Spent in a Particular Activity “A”

Total Nuber of Participants in Activity “A”

Unpaid care work is defined to be the production of services, and hence, not of goods, either for own final consumption or for others (ILO 2018). These services are rendered for meeting the care needs of the household members that do not receive any direct remuneration from the market. The activities included under the domain of “unpaid care work” adhere to Margarate Reid’s (1934) third- party criterion- a third person can replace the activity. Hence, it does not involve the activities such as sleeping, eating, bathing, grooming, etc., so far as someone else can’t replace these activities. Unpaid care work encompasses three components- (1) unpaid domestic services for the household members, (2) unpaid direct caregiving services for the household members, and (3) unpaid volunteer and community services (ILO 2018, Budlender 2010). The unpaid domestic services for the household members, i.e., cooking, cleaning, shopping, etc., are also termed as secondary or indirect care work. This is mainly because the nature of the activities is such that it does not give rise to the direct or intimate relationship between the caregiver and care receiver. On the other hand, unpaid direct caregiving services, i.e., childcare, elder care, care for the sick and disabled household members, etc., build such kind of relationship involving emotional and cognitive elements. Unpaid volunteer and community services are also termed as help to other household members. In simple parlance, it includes the care-related services rendered voluntarily for the members of other households. Such caregiving services could either be direct care work or indirect care work (domestic services).

V Empirical Results and Discussion

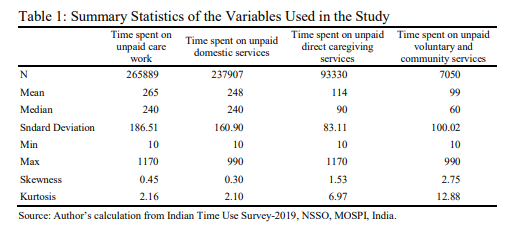

Before proceeding with the analysis, we have provided the summary statistics of the variables used in the study

As we can see from the Table 1, the number of observations is quite large across the variables and ranges from 7050 (for unpaid voluntary and community services) to 265889 (for unpaid care work as a whole). Unpaid domestic services stand out to be the largest component of unpaid care work. The magnitude of the mean time spent on unpaid care work, on a daily basis, is 265 minutes. Among the components of unpaid care work, the mean time spent in unpaid domestic services is relatively higher (248 minutes) compared to unpaid direct caregiving services (114 minutes) and unpaid voluntary and community services (99 minutes). Likewise, the median time devoted to unpaid care work, on a daily basis, is 240 minutes. In the case of unpaid domestic services as well, it remains to be 240 minutes but varies substantially between unpaid direct caregiving services (90 minutes), and unpaid voluntary and community services (60 minutes). The magnitude of the values of mean time spent remains to be relatively higher than the values of the median time spent, for all the variables under study. The standard deviation is higher for unpaid care work (186.51) and unpaid domestic services (160.90), but noticeably lower for unpaid direct caregiving services (83.11) and unpaid voluntary and community services (100.02). Hence, the values of unpaid care work and unpaid domestic services are highly dispersed (from the mean) compared to the values of unpaid direct caregiving services and unpaid voluntary and community services. The minimum value of time spent remains to be the same (10 minutes) for all the variables. However, the maximum values differ significantly. The maximum values remain to be 1170 minutes for unpaid care work (combined) and unpaid direct caregiving services (one of the components); whereas, it is 1170 minutes and 990 minutes respectively for unpaid direct caregiving services and unpaid voluntary and community services. The distribution of values of all the variables is positively skewed (coefficient of skewness>0). The degree of skewness is higher for unpaid direct caregiving services (1.53) and unpaid volunteer and community services (2.75) relative to unpaid care work (0.45) and unpaid domestic services (0.30). The time spent on unpaid care work and unpaid domestic services represents platykurtic curves (values of kurtosis<3). However, the time spent on unpaid direct caregiving services and unpaid volunteer and community services are leptokurtic (the values of kurtosis>3).

Patterns of Unpaid Care Work Distribution: The Gender-Space Interaction

Note: *gender gap=female-male.

Source: Author’s estimation from Indian Time Use Survey-2019, NSSO, MOSPI, India.

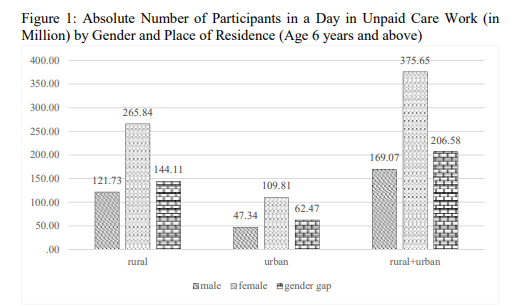

It could be observed from Figure 1 that there exists a striking gender disparity as well as a rural-urban difference in the distribution of unpaid care work. The estimated result shows that a gender gap of 206.58 million appears in the country as a whole (rural + urban). The absolute number of women carrying out unpaid care work stands out to be more than twice (2.22 times higher) compared to that of the male counterparts in the country as a whole. It has been estimated that

375.65 million females (6 years of age and above) are carrying out unpaid care work and only 169.01 million males (6 years of age and above) are carrying out such work. However, this gender difference is significantly lower in urban India (62.47 million) than in rural India (144.11 million). While 109.81 million females and 47.34 million males are carrying out unpaid care work in urban India, 265.84 million females and 121.73 million males are carrying out such work in rural India (Figure 1).

However, the aforementioned differences in unpaid care work distribution are in terms of absolute no. of participation. This could arise, for instance, due to the differences in population across the rural-urban stratum. Hence, it is imperative to understand the dynamics in terms of the percentage rate of participation.

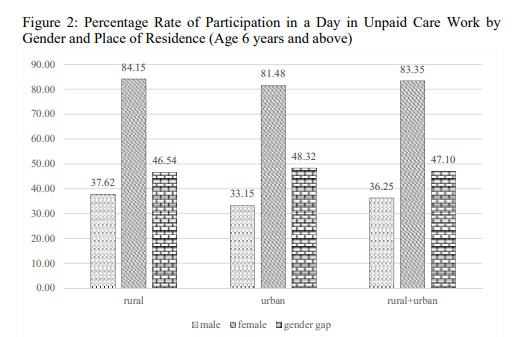

As can be seen from Figure 2, a stark gender gap exists, in terms of the percentage rate of participation, in unpaid care work in the rural and the urban areas separately as well as in the country as a whole (rural + urban). A gender gap

of 47.10 per cent exists in the country. Simply put, the proportion of women engaged in unpaid care work (who are 6 years of age and above) is more than twice (2.30) compared to that of their male counterparts. The extent of this gender gap remains more or less equal in the rural and urban regions of the country: the rural- urban difference for the gender gap, specifically, being rural-biased is 1.78 per cent6.

Note *gender gap=female-male.

Source: Author’s estimation from Indian Time Use Survey-2019, NSSO, MOSPI, India.

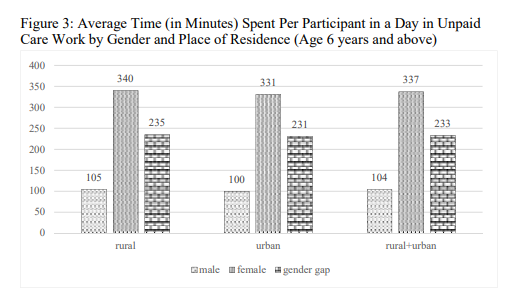

The gender gap, in terms of average time spent per participant in a day, in unpaid care work is a matter of concern. The gap stands out to be 233 minutes, on average, in the country as a whole. While girls and women are devoting 337 minutes, on average, a day, boys and men are devoting only 104 minutes, on average, a day. Simply put, females, who are of 6 years of age and above, are spending time more than thrice (3.24) in unpaid care work in comparison to that of their male counterparts. In urban India, the gender gap in the average time allocated to unpaid care work is 231 minutes and in rural India, this is 235 minutes. Females are devoting, on average, 331 minutes a day, and males are devoting, on average, only 100 minutes a day in urban India. In rural India, females are devoting, on average, 340 minutes a day, and males are devoting, on average, only 105 minutes a day.

Note: *gender gap=female-male.

Source: Author’s estimation from Indian Time Use Survey-2019, NSSO, MOSPI, India.

No significant difference, from that of urban India, in gendered time allocation pattern on unpaid care work is there in rural India. Hence, the intra- family time allocation on unpaid care work is strongly on gender lines, and persisst more or less equally in rural and urban regions of the country. It is worth noting down here, that girls and women are not only participating more in unpaid care work, but they are also bearing more time while performing such work relative to their male counterparts.

Gender Dynamics in the Components of Unpaid Care Work

Unpaid Domestic Services for the Household Members

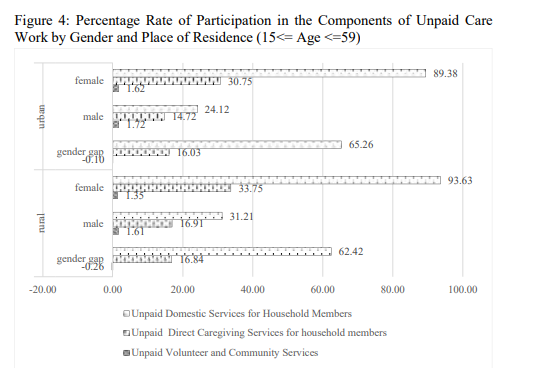

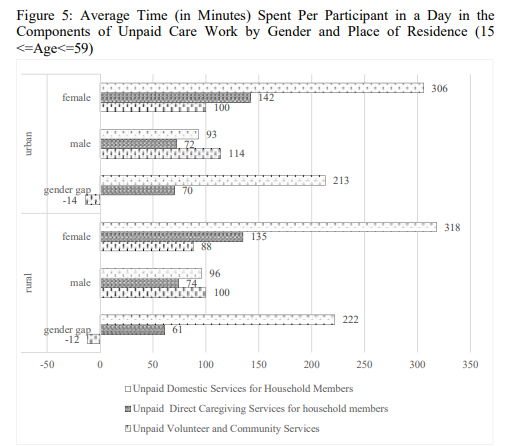

It is worth illustrating the distribution of unpaid care work across the gender and places of residence considering its components (sub-categories of unpaid care work). The unpaid domestic services carried out within the household premises receive the highest proportion of participation among other components both in rural and urban regions (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The participation rate of both males and females is the highest for this category of unpaid care work, though a sharp gender gap persists both in rural and urban regions. It has been estimated that around 89 per cent of females during their productive age (15-59), in urban India, are engaged to provide unpaid domestic services for the household members (Figure 4). Only around 24 per cent of urban males, during their productive age (15-59), are engaged to provide such services. There exist a gender gap of around 65 per cent, in the case of the participation in unpaid domestic services for the household members, in urban India. In rural India, the spatial dynamics of the rate

of participation in unpaid domestic services seem to be marginally different from that of urban India. As can be seen from Figure 4, around 94 per cent of the rural females, in their productive age, are engaged to provide domestic services for the household members, and only around 31 per cent of the rural males are engaged to perform such tasks. There exist a gender gap of around 62 per cent for this category in rural India. The proportion of working-age girls and women engaged in this category is around four times (3.71) higher than boys and men in urban regions. However, the proportion of working-age girls and women engaged in this component stands out to be three times higher than boys and men in the rural regions.

Note: *gender gap=female-male.

Source: Author’s estimation from Indian Time Use Survey-2019, NSSO, MOSPI, India.

The gender relation, in terms of the time utilization, in the components of unpaid care work is quite interesting. As can be seen from Figure 5, females belonging to the working-age cohort are devoting, on average, 306 minutes per day to unpaid domestic services carried out for household members in urban India. However, males are devoting, during their working-age period, on average, only 93 minutes per day to such services in urban India. The average time spent per participant, on a daily basis, by females is more than three times (3.29) in comparison to the male counterparts. There exists a sharp gender gap of 213 minutes, on average, in this region. In rural India, females are spending, on

average, 318 minutes per day, while males are spending only 96 minutes per day on such services. Females, in this region, are also spending more than three times (3.31) on unpaid domestic services. A gender gap of 222 minutes exists in rural India which is moderately higher than that in urban India. The average time allocated to unpaid domestic services both by males and females is, though not visibly large, higher in rural India than in urban India (Figure 5).

Note: *gender gap=female-male.

Source: Author’s estimation from Indian Time Use Survey-2019, NSSO, MOSPI, India.

Unpaid Direct Caregiving Services for the Household Members

The second crucial component of unpaid care work is the component of unpaid direct caregiving services carried out for the household members. The estimated result shows that around 31 per cent of urban females and around 15 per cent of urban males, who belong to the age cohort 15-59, are providing such services on a daily basis. There exists, evidently, a gender gap of around 16 per cent in terms of participation in this component in the urban areas. Around 34 per cent of rural

females and around 17 per cent of rural males are providing such caregiving services on a daily basis. A gender gap of around 17 per cent exists in terms of the rate of participation in such caregiving services in rural India. The extent of the proportion of participation in unpaid caregiving services is marginally rural biased. Rural females are spending 135 minutes a day, on average, in this component; whereas urban females are devoting around 142 minutes, on average, per day to such caregiving services. Hence, females residing in urban India are devoting a marginally higher amount of time to unpaid caregiving services when compared with rural females’. Male members are devoting the least amount of time, on average, to such services: rural males are devoting 74 minutes, on average, a day, and urban males are devoting 72 minutes, on average, a day. In the case of this component, a gender gap of around 61 minutes persists in rural India, whereas a

gender gap of 70 minutes persists in urban India.

As the figure reflects, the gender gap in terms of average time allocated to unpaid domestic services is lower in urban India, when compared with that of rural India, if compared with the gender gap in terms of average time spent in unpaid direct caregiving services. This finding indicates that girls and women residing in urban India, though spend lesser time in the indirect caregiving services like cooking, cleaning, decorating the house, etc., spend a higher amount of time in direct caregiving services like childcare, elder care, caring for the disabled persons residing in the household, etc. Hence, though the notion of patriarchy prevails more or less the same in rural and urban India, its influence on the activities under unpaid care work remains to be slightly different.

Unpaid Voluntary and Community Services/Help to Other Household Members

Finally, unpaid volunteer and community services/help to other household members receive the least proportion of participants, in between 1-2 per cent, both in rural and urban regions. Since male members are more likely to participate in such services, the gender gap stands out to be negative. This is the single component of unpaid care work where a higher proportion of male members participate. However, the negative gender gap, in terms of participation, for this component is higher in rural India (-0.26) than that in urban India (-0.10).

In terms of average time spent as well, male members are spending a higher amount of time in comparison to that of their female counterparts, both in rural and urban India. In rural areas, on an average, 100 minutes are devoted to such services by males and 88 minutes by females. A gender gap of -12 minutes prevails in rural India. In urban India, male members devote 114 minutes, on average, per day and female members devote 100 minutes, a day, on average. A gender gap of

-14 minutes prevails in urban India for this component. Hence, male members bear a slightly larger share of unpaid volunteer and community services in urban India than in rural India.

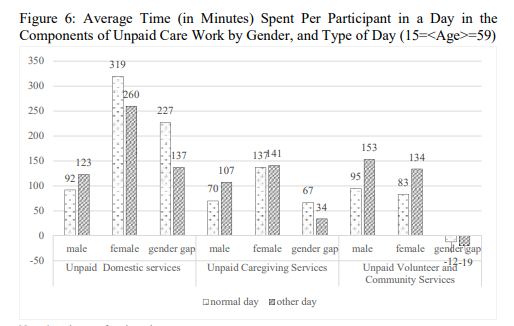

Distribution of Unpaid Care Work During the Normal Days and Other Days

The nature of the day on which unpaid care work is carried out, plays a vital role in determining the quantum of time allocated to unpaid care work across the gender. It is quite intriguing to scrutinize the intra-family allocation of time on unpaid care work, specifically on the components of unpaid care work, throughout normal days and other days. The normal days are the usual days on which household members perform their routine activities. On the other hand, other days are the days on which the household members’ routine activities are altered. For instance, a household member’s time allocation pattern for routine activities may get distorted because of social obligations or unforeseen reasons like illness, ceremonies, hospitalization of a household member or duties thrust upon due to an accident, etc. besides, weekly off-days, holidays, or days of leave. On such days (other days), the gendered time allocation pattern alters considerably as discussed below;

Note: *gender gap=female-male.

Source: Author’s estimation from Indian Time Use Survey-2019, NSSO, MOSPI, India.

As Figure 6 shows, male members are devoting 92 minutes on average per day to unpaid domestic services on normal days, whereas the quantum of time allocated to it increases significantly to 123 minutes per day , on average, on other days. Conversely, female members are devoting 319 minutes, on average, on a normal day; and 260 minutes, on average, on other days to unpaid domestic services. It is worth noting down here that a male’s quantum of time allocated to

unpaid domestic services, increases by 31 minutes and a female’s time allocated to unpaid domestic services decreases by around 60 minutes, due to alteration in the nature of the day (change from a normal day to other days) (See Figure 6). Hence, on other days, male members devote a higher amount of time (around half an hour more) to unpaid domestic services and female members devote a lower amount of time (around an hour less) to it. The gender gap in terms of time allocated to unpaid domestic services, is higher on a normal day and lower on other days. This indicates that male members are mostly available in the family during the other days, and hence are allocating extra time to unpaid domestic services. However, the reduction of minutes devoted to unpaid domestic services by females is higher than the increase in the minutes devoted to it by males. This could be due to the strict notion of patriarchy that is holding them back, and as a result of which they (men) are not compensating fully for the reduction of time on unpaid domestic services which was earlier being performed by females in the household.

Male members devote 70 minutes, on average, on a normal day, and surprisingly 107 minutes, on average, on other days to unpaid direct caregiving services. Likewise, female members devote 137 minutes, on average, on a normal day, and 147 minutes, on average, on other days in such services. Hence, the time devoted to unpaid domestic services increases both for males and females; but the quantum of increase is higher for males (34 minutes more) than that for females (only 4 minutes higher). This could be because male members become more caring during an unusual time like when family members succumb to sickness or injuries due to accidents. They spend more time on person-care activities like hospitalizing the sick or injured family members on other days. The gender gap in terms of time devoted to unpaid direct caregiving services is lower (around half) on the other days than that on a normal day.

In the case of unpaid volunteer and community services as well, both the males and females spend a higher amount of time on the other days in comparison to the normal days. For males, time utilization on this component of unpaid care work increases by 58 minutes, on average, during unusual days; and, for females, it increases by 51 minutes, on average, during unusual days. The finding suggests that despite bearing the bulk of unpaid domestic and caregiving services, girls and women spare extra time for volunteer and community services during unusual times. In the case of the males, though, the time devoted to this component remains to be relatively higher during normal times and increases further during unusual times. The gender gap remains to be negative on both the normal days and the other days, but the gap is considerably larger on the other days than that on the normal days. This finding again suggests the prevalence of the patriarchal notion which is consequently responsible for the gender-biased time allocation during unusual times: male members spare a relatively higher amount of time on out-of- home activities (voluntary and community services per se) during the other days. So far as voluntary and community services are preferred out of one’s own choice owing to altruistic motives, male members allocate a higher amount of time, as the findings suggest, to such tasks and often enjoy improved social statuses.

II Concluding Remarks

The purpose of the paper is twofold: one is to explore the debates surrounding unpaid care work, and another one is to examine empirically the patterns of unpaid care work distribution across the gender lines in India. With the help of the data from the first pan Indian Time Use Survey-2019 (ITUS-19), we examined the working of the gender dynamics both in the rural and urban spaces. The findings show the existence of a sharp gender gap, both in terms of participation and average time allocation, in unpaid care work in India. The disproportionate participation and time allocation of Indian women in unpaid care work could be due to socio-religious constraints, the failure of markets and states to provide basic amenities in the domestic sphere, and the low opportunity cost of unpaid care work in the market (Singh and Patnaik 2020). The over-representation of women in unpaid care work makes them vulnerable on many grounds i.e. in terms of socio- economic status, participation in the paid labour market, freedom of choice over working opportunities, etc. which results in depriving them of many rights. Hence, the development practitioners, authorities, and policymakers must pay attention to designing gender-sensitive care policies in India. The three R-approaches, as suggested by contemporary feminist scholars, of responding to the gender-biased distribution of unpaid care work such as Recognition, Reduction, and Redistribution need to be considered.

Endnotes

1. The term “passive care” has been coined by Himmelweit (2007).

2. For the detailed information, look at Barrios de Chungara and Viezzer 1978, p. 35.

3. However, cleaning is a special case and can’t be mechanized as it is labour intensive and its product can be noticed only when the work is not done (Hensman 2011, p.16).

4. The survey was a pilot one, and hence, did not cover the entire country. Only six states were considered for the survey.

5. This is mainly due to the difficulty in accessing the respondents.

6. Rural and urban difference in the gender gap (%)= gender gap in urban area (%)-gender gap in rural areas (%).

References

Benería, L. (1979), Reproduction, Production, and the Sexual Division of Labour, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 3(3): 203-225.

Benston, M. (1969), The Political Economy of Women’s Liberation, Monthly Review, September. Berik, G. and E. Kongar (2021), The Routledge Handbook of Feminist Economics (Eds.), Routledge. Bhattacharya, T. (2017), Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression,

Pluto Press.

Braedley, S. (2006), Someone to Watch Over You: Gender, Class, and Social Reproduction, In Social Reproduction: Feminist Political Economy Challenges Neoliberalism, Edited by Kate Bezanson and Meg Luxton (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press).

Budlender, D. (2010), Time Use Studies and Unpaid Care Work, Routledge, London.

Chhachhi, A. (2004), Erodingcitizenship: Gender and Labour in Contemporary India, The University of Amsterdam.

Dalla Costa, M. and S. James (2017), The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community, Class: The Anthology, 79-86.

De Chungara, D.B. and M. Viezzer (1978), Let Me Speak: Testimony of Domitila, a Woman of the Bolivian Mines, Translated by Victoria Ortiz, New York: Monthly Review Press.

England, P. (2005), Emerging Theories of Care Work, Annual Review of Sociology, 31(2005): 381- 399.

Esquivel, V. (2021), Care Policies in the Global South, In Berik, G., and E. Kongar (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Feminist Economics, Routledge.

Ferguson, A. and N. Folbre (1981), The Unhappy Marriage of Patriarchy and Capitalism, In Women and Revolution, Edited by Sydia Sargent, South End Press: 313-338.

Ferguson, S. (2020), Women and Work: Feminism, Labour and Social Reproduction, London, UK: Pluto.

Firestone, S. (1970), The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, New York: Morrow.

———- (2000), The Dialectic of Sex, Radical Feminism: A Documentary Reader, 90.

Folbre, N. (1995), Holding Hands at Midnight: The Paradox of Caring Labor, Feminist Economics, 1(1): 73–92, doi:10.1080/714042215

———- (2001), The Invisible Heart: Economics and Family Values, New York: New Press.

———- (2017), The Care Penalty and Gender Inequality, The Oxford Handbook of Women and Economy, pp. 1-28.

———- (2018a), Developing Care: Recent Research on the Care Economy and Economic Development, Ottawa, ON: International Development Research Centre.

———- (2018b), Gender and the Care Penalty, In Oxford Handbook of Women in the Economy, Edited by Laura Argys, Susan Averett, and Saul Hoffman, New York: Oxford University Press.

Hensman, R. (2011), Revisiting the Domestic-Labour Debate: An Indian Perspective, Historical Materialism, 19(3): 3-28.

Himmelweit, S. and S. Mohun (1977), Domestic Labour and Capital, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 1(1): 15-31.

Hochschild, A. (1983), The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling, Berkeley: Univ.

Calif. Press.

Ilkkaracan, I. and E. Memis (2021), Poverty, In Berik, G. and E. Kongar (Eds.), The Routledge

Handbook of Feminist Economics, Routledge.

International Labour Organisation (ILO) (2018), Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work, Op. cit.

———- (2018), Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work, Geneva.

Johanna Brenner and Barbara Laslett (1991), Gender, Social Reproduction, and Women’s Self- Organization: Considering the US Welfare State, Gender and Society, 5(3): 311-333

Kabeer, N. (2021), Three Faces of Agency in Feminist Economics: Capabilities, Empowerment and Citizenship, in Handbook of Feminist Economics, Günseli Berik and Ebru Kongar (Eds.), New York: Routledge.

Kimmel, J. and R. Connelly (2007), Mothers’ Time Choices: Caregiving, Leisure, Home Production, and Paid Work, University of Wisconsin Press Stable, 42(3): 643–681.

Luxton, M. (2006), Feminist Political Economy in Canada and the Politics of Social Reproduction, in Social Reproduction: Feminist Political Economy Challenges Neoliberalism, Edited by Kate Bezanson and Meg Luxton (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press).

Marx, K. (1977), Capital, Vol. 1, New York, NY: Vintage Books. Millett, K. (1970), Sexual Politics, New York: Doubleday.

Molyneux, M. (1979), Beyond the Domestic Labour Debate, New Left Review, 116(3): 3-27.

Moos, K.A. (2021), Care Work, In The Routledge Handbook of Feminist Economics, pp. 90-98, Routledge.

Neetha, N. (2010), Estimating Unpaid Care Work: Methodological Issues in Time Use Surveys,

Economic and Political Weekly, xlv(44): 73-80.

Neetha, N. and R. Palriwala (2010), Unpaid Care Work: Analysis of the Indian Time Use Data, In Budelender, D. (Eds.), Time Use Studies and Unpaid Care Work, Routledge, London.

Nelson, J. (1999), Of Markets and Martyrs: Is It OK to Pay Well for Care? Femimist Economics.

5(3):43– 59

———- (2004), Feminist Economists and Social Theorists: Can We Talk? Work. Pap., Glob. Dev.

Environ. Inst., Tufts Univ.

Nelson, J. and P. England (2002), Feminist Philosophies of Love and Work, Hypatia, 17(2): 1-18. Petersen, T. and L.A. Morgan (1995), Separate and Unequal: Occupation-Establishment Sex

Segregation and the Gender Wage Gap, American Journal of Sociology, 101(2): 329-365.

Rao, N. (2018), Feminist Mobilization, Claims Making and Policy Change Global Agendas, Local Norms: Mobilizing Around Unpaid Care and Domestic Work in Asia, 49(May 2016): 735– 758, https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12390

Razavi, S. (2007), The Political and Social Economy of Care in a Development Context: Conceptual Issues, Research Questions and Policy Options, Gender and Development Programm Paper, 3, UNRISD, Geneva.

Sorensen, E. (2019), Comparable Worth, Princeton University Press.

Steinberg, R. (2001), Comparable Worth in Gender Studies, In International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences, N.J. Smelser and P.B. Baltes (Ed.), pp. 2393–2397, Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press.

Vogel, L. (2000), Domestic Labor Revisited, Science and Society, 64(2): 151-170.

———- (2013), Domestic Labour Revisited, In Marxism and the Oppression of Women, pp. 183- 198), Brill.

Zelizer, V. (2002), How Care Counts, Contemporary Sociology, 31(2): 115–19.

———- (2002b), Intimate Transactions, In The New Economic Sociology: Developments in an Emerging Field, M.F. Guillen, R. Collins, P. England, M. Meyer (Eds.), pp. 274–300, New York: Russell Sage Found.