Human Capital, Institutional Quality and Economic Growth - The Mediating Effect of Digital Adoptions, Creative Outputs, and Total Factor Productivity

September 2023 | Seema Joshi

I Introduction

The paper aims to examine the interaction between human capital (HC), quality of institutions (IQ) and economic performance. Beginning in the 18th century (Smith 1776) and followed by the influential writings of several economists belonging tothe new school of institutional economics (North 1990, North and Thomas 1973, Hall and Jones 1999, Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson and Tchaichoroen 2003; Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson 2005) have subsequently brought this relationship between IQ and economic growth to prominence in the economic literature (Knack and Keefer [1995], Mauro [1995], Hall and Jones [1999], Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi [2004] Beirne and Panthi [2022]). There are also a few studies (Lipset 1960, Glaeser, et. al. 2004) that investigate the effect of human capital on political institutions and thereby on economic performance. However, to our knowledge, few studies have tried to capture and analyse the impact of human capital (HC) on institutional quality (IQ) by mediating variables such as the digital adoption index (DA), creative outputs (COs), and total factor productivity (TFP), which have emerged as important drivers of economic growth with globalization, the onset of Industry 4.0 (Skare and Soriano 2021, Sainee, Kamat, Prakash and Weldon 2017) and the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, no other study tries to parse the direct and indirect effects of the key variables on each other as well as on IQ, which in turn fosters economic growth. As a novelty, the present study attempts to address all the aforementioned gaps in the previous research and that too in the context of Asian economies. It contributes to the literature on the interaction between human capital (HC), institutional quality (IQ), and growth (EG) by using the path analysis technique. Although multiple regression models have been widely used in social science research, there are too many contentious issues related to their use. The problem of multicollinearity, non-simultaneous estimation of parameters, absence of overall goodness of fit indices, etc. /might be faced by the researchers while using this method. We preferred to use the path analysis technique in this paper, as many of the above- cited limitations of the multiple regression techniques are addressed by the path analysis method and in an unambiguous manner (see Min and Mishra 2010). The paper sets out the hypothetical model based on the literature review in Section II, which is followed by sources of data, methodology, empirical evidence, conclusions and policy implications later.

II Presentation of a Hypothetical Model Based on a Review of Literature

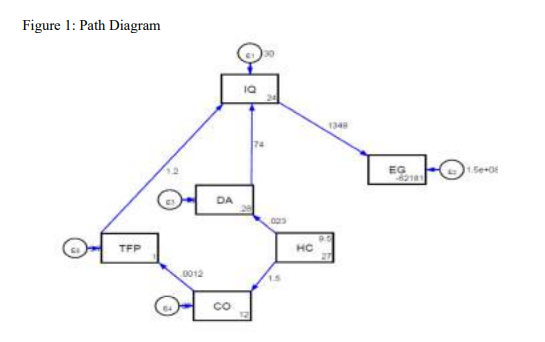

Figure 1 gives a hypothetical model that provides a visual representation of the relationship between endogenous and exogenous variables. The arrows are used in the path diagrams to indicate the hypothesized structure of relationships among the key variables. When an arrow is directed from an exogenous (independent) variable to the endogenous/dependent variable, then this is called the direct effect. For example, in the path diagram given below, the EG is the dependent variable and is influenced by IQ directly, as indicated by the direction of an arrow.

Studies referenced earlier show that institutions are a major determinant of economic outcomes. A few studies (Lipset 1960, Glaser, La Porta, Silanes and Shleifer 2012, Bekana 2020) also show that human capital impacts institutional quality. However, our argument in this paper is that it is the level of human capital that will determine the quality of the labor force by encouraging digital adoption (Foster and Rosenzweig 2010) and by facilitating the generation of creative outputs. Both digitization and creative outputs have a productivity-enhancing effect (Chiemeke and Imafidor 2020, Bahrini and Qaffar 2019, Nwankwo 2018, Falk and Biag 2015, Florida, Mellander and Stolarik 2008) and have the potential to positively impact institutional quality and economic growth (Finger 2007). Undeniably, greater access to knowledge and tech adoption will have several positive implications for employment, productivity and accountability in politics, government and businesses. This interaction can help increase economic growth. However, the potential of DA and CO will be untapped if quality HC is not available. HC is indispensable for accelerating DA, the growth of creative industries and improving productivity. Undeniably, it is HC that adds to the absorptive and innovative capacity of the economy (Bye and amp, Faehn 2021). Studies (Nelson and Phelps 1966, Benhabib and Spiegel 1994, Bodman and Le 2013) have established that technology adoption becomes easier when people are educated.

In the hypothesized path model, the variables (such as DA, CO, and TFP) are termed ‘mediating variables’ (between HC and IQ). The inclusion of variables in the model is justified based on a comprehensive review of the literature. A unique feature of this path model is that it allows for studying direct and indirect effects simultaneously. It enables us to parse the effects of HC on DA and IQ (HC ͢͢ DA ͢ IQ) on the one hand and the effect of HC on CO, TFP, and IQ (HC ͢͢ CO ͢ TFP ͢IQ) on the other hand. It helps us to identify the factors that act on IQ directly (such as DA and TFP) and indirectly (such as HC affecting IQ through DA and by affecting CO and TFP).

The direct effect of DA on IQ is 73.8/74, as exhibited by the arrow directed from DA to IQ, and that of TFP is 1.2.

However, the indirect effect of HC on IQ works via DA and via CO and TFP. The indirect effects are obtained by multiplying the coefficient for each path, e.g.

HC ͢͢ DA ͢ IQ is (.023*.74) = 1.633 …(i)

HC ͢͢ CO ͢ TFP ͢IQ is (1.5*.0012*1.2) = 0.00216 …(ii)

Total indirect effect [sum up (i) and (ii)] = 1.633+0.00216=1.63516 The indirect effect of HC on IQ is 1.63516 and is positive.

II Data Sources and Methodology

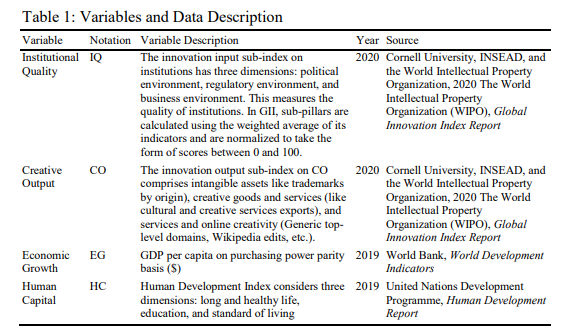

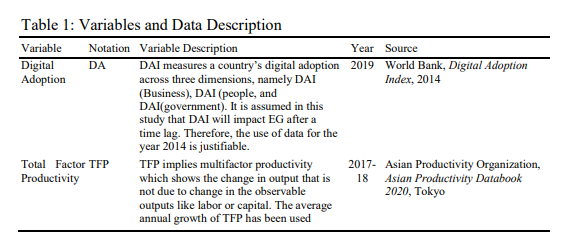

The study empirically explores the contributions of HC to IQ and EG in selected Asian countries. We gathered data for 18 countries from various sources. The selection of countries was based on the availability of data for the variables that we chose. The list of the variables used in the study along with the data sources is as follows

II Empirical Evidence and Discussion

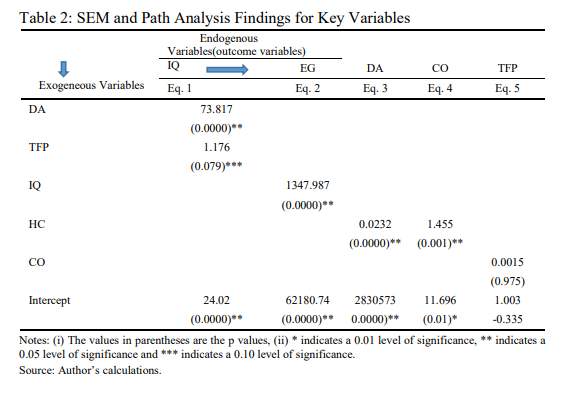

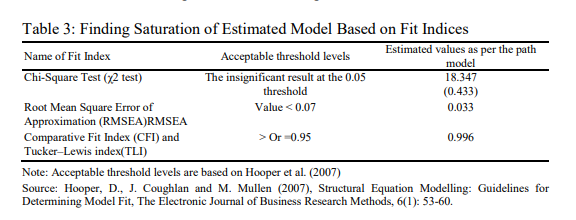

A path analysis using the statistical software STATA 15 was performed to analyse the impacts on institutional quality and EG. The coefficients have been computed using the maximum likelihood method, and the model fit is justified using several methods explained in Table 3. The empirical exercise yielded five linear relationships among endogenous variables, namely, IQ, EG, DA, CO, and TFP, as shown in Table 2. The interpretations of the results are as follows:

| 1 |

The estimated slope coefficient for DA (b DA) = 73.817 (see Table 2) for predicting IQ indicates that for every unit increase in DA holding TFP constant, IQ improves by 73.817, and this is found to be significant. The results are in keeping with recent studies (Chiemeke and Imafidor 2020, Bahrini and Qaffar 2019, Falk and Biag 2015).

| 2 |

The estimated slope coefficient for TFP (b TFP= 1.176) for predicting IQ indicates that for every one-unit increase in TFP (holding DA constant), IQ improves by 1.176. TFP has a significant impact on IQ. This result is also consistent with several other empirical studies (Hall and Jones,1999; Jankauskas and Seputiene 2007 and Kassa 2016) that found a positive and significant association between labor productivity and IQ.

Coming now to the interpretation of multivariate regression results for Equation 2 on EG.

| 0 |

The Intercept of EG (b EG) =-62180.74, the value of EG when all predictors are zero (IQ=0).

| 1 |

The slope coefficient of IQ (b IQ) =1347.987, predicting EG, indicated that for every unit improvement in institutional quality, economic growth spurs by 1347.987. This is in keeping with the large literature referenced earlier on IQ and EG (Knack and Keefer [1995]; Mauro [1995]; Hall and Jones [1999]; Rodrik, et. al. [2004] Beirne and Panthi [2022]).

The interpretation of Equation 3 on DA is as follows:

- The intercept of DA (b0DA) =–283057, the value of DA when all predictors are zero (HC=0).

- The slope coefficient of HC (b1HC) =.02324, predicting DA, indicated that on average, for every unit improvement in human capital (HC), digital adoption (DA) increases by.02324.

It is important to mention here that human capital (Gorodnichenko and Roland 2010, Yamamura and Shin 2012, Ghulam 2012, Sharpe 2004, Isaksson 2007) and innovation (DA also indicates tech innovations) have been viewed and confirmed to be crucial factors affecting productivity (Bye and Faehn 2021, Crespi and Zuñiga 2010, Peters, Loof and Janz 2003, Hall 2011, Isaksson 2007, Sharpe

2004).

The interpretation of Equation 4 on Creative outputs (CO) is as follows:

- The intercept of CO (b0CO) = 11.696, the value of CO when all predictors are zero (HC=0).

- The slope coefficient of HC (b1HC) =1.4553, predicting CO, indicated that for every unit improvement in human capital (HC), CO increases by 1.4553. This is in line with the study done by Florida, et. al. [2008], which finds that HC and creative class play a complementary role in regional development. Nwankwo (2018) emphasizes harnessing the untapped potential of the

creative industry through policy interventions that can contribute much more to overall growth through employment and revenue generation.

Now, we come to the interpretation of multivariate regression results for Equation 5 on TFP.

| 0 |

The intercept of TFP (b TFP) =1.0039, the value of TFP when all predictors are zero (CO=0).

| 1 |

The slope coefficient of TFP (b CO) =.00115, predicting TFP, indicated that for every unit improvement in CO, TFP registers an increase of.00115. Our result shows that CO has a positive but not significant association with TFP. Our result lends support to the findings of Florida et al. 2008, who also found relatively high levels of association between artistic and entertainment occupations (i.e., creative class) and regional labor productivity.

After the estimation of the model, we proceeded to assess whether our estimated model is saturated or the best fit model or not, following the insights provided by Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen [2007] in their work. It is important to mention that the goodness of fit/fit indices help a researcher to assess how well the observed data match a probability distribution. There are a variety of fit indices available. However, Table 3 below provides a summary of the estimated values of various indices from the path model and acceptable threshold levels.

The table given above clearly shows that our estimated model turns out to be the best fit model, as the threshold levels needed by the four fit indices viz. A chi- squared test (χ2 test), RMSEA, CFI, and TLI are present, clearly showing that the specified model is accepted.

The model fit indices are interpreted as follows:

The traditional method used for evaluating overall model fit is the chi-square value (Hu and Bentler 1999) obtained through the chi-square test (χ2 test). It helps us to assess the discrepancy, if any, in the magnitude of covariance matrices between the sample and fitted matrices. A model is said to be fit if the estimate or statistics turns out to be insignificant at the 0.05 threshold (Barrett 2007). Since this happens to be the case in the empirical exercise carried out in the present study (see Table 3), the proposed model is indeed a good fit model.

We have also used another criterion (namely RMSEA), which is said to be ‘one of the most informative fit indices’1 (Diamantopoulos and Siguaw 2000). RMSEA was developed by Steiger and Lind (1980, cited in Steiger 1990). In the case of RMSEA (the said fit index), a stringent upper limit of 0.07 is regarded as an indication of a fairer fit (Steiger 2007). The value of the statistic in our model is 0.033, which is less than 0.07. Therefore, this indicates that our model is a fairer fit.

Utilizing two other fit indices, namely, the comparative fit index (CFI, which is insensitive to sample size2) and Tucker–Lewis’s index (TLI), it has been found that the proposed model is an excellent fit. In the case of both these indices, a value greater than or equal to 0.95 is indicative of a good fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). In the case of our study, the value of the statistic stands at 0.996, and it indeed represents an excellent fit.

Given the plethora of fit indices, we have chosen the four fit indices (see Table 3) that indicate that our model is the saturated one of the best fit models and reflects different aspects of model fit, as has been emphasized by Crowley and Fan (1997).

II Conclusion and Policy Implications

The path model developed in this paper demonstrates the importance of the interaction between human capital and IQ for exploring the growth process. The literature acknowledges that IQ plays a key role in fostering the EG. However, the pivotal role of human capital in encouraging digital adoption, facilitating the generation of creative outputs, and boosting productivity, institutional quality, and economic growth is largely unresearched, especially in the context of Asian economies. That is how the present study assumes importance. Our study is the first to our knowledge to use path analysis and complex variables such as DA and CO, among others, to evaluate their impact on IQ (via TFP improvements) and EG. The empirical estimates obtained by us, using cross-section data of 18 Asian countries and applying maximum likelihood methods of estimation corroborates some insights from the path model visualized by us.

The present paper reveals that DA and IQ are positively and significantly related. Earlier studies have shown that digital technology penetration and adoption can have a critical effect on innovation and productivity along with other socioeconomic benefits. Digital adoption presupposes the availability of digital infrastructure. However, digital adoption in some Asian countries is still in the stage of infancy, due to various reasons, such as a low level of investments in ICTs (information communication technologies), inaccessibility or low accessibility of digital technologies, and a low level of digital maturity. Digital illiteracy along with the negative perception about the adoption and usage of technologies are other hurdles on the path of digital transformation of these economies. Therefore, the role of policymakers and policy interventions in incurring higher IT spending (for building digital infrastructure), promoting ‘digital literacy’,’ digital skills’,

and ‘digital inclusion’ by plugging the ‘digital divide’3 is crucial. Nurturing ‘digital maturity and ‘digital mindset’ through building a culture of understanding by ‘a rotation of mindset’ in addition to removal of ‘mistrust of technologies’ by launching awareness campaigns and tailored programs is a must. This will allow everyone to access and use digital technologies. The respective governments, through policy articulation and implementation, must strive to create an enabling environment for digital transformation via higher IT spending, boosting digital skills sets along with refining practices to be followed by government and nongovernment bodies, including corporations (Accenture 2017), to realize the full impact of digital technologies on economic performance/prosperity (by improving the quality of institutions). Extending the benefits of digital information, products, and services equally and equitably through the enabling and regulatory mechanisms can also help attain the goal of ‘digital inclusion’.

Our study also highlights the positive association between HC and DA, and HC and CO generation. Therefore, in addition to HC development and digital adoption strategies, there is a need for formal governmental intervention in these countries to map the creative goods and services sector, which is largely an untouched sector in many developing Asian economies. Knowing fully well the positive impact of COs on TFP (through this study), it is imminent that governments in the selected Asian economies must articulate a coherent policy to develop, deepen, support, and promote the creative industries and the services sectors and also check the challenges of intellectual property protection so that the full potential of this sector is optimally used. Obtaining a high level of productivity by improving the effectiveness of HC and creative (industries and services) sectors, should be set as an important mid- and long-term aim of economic policy in these selected countries.

Our research unearthed the positive impact of IQ on economic growth in a very unique way by factoring in the role of HC and DA. Therefore, in addition to checking the ‘digital technologies void’ (wherever it exists), policymakers will have to design effective policies to plug the ‘institutional void’ too, wherever it is present. Any policy lacuna in these respects has the potential to make transactions (government and business as well) scarcer and riskier. ‘The pervasive power of digital transformation and ‘creative outputs ‘in boosting productivity and economic growth through IQ might remain unrealized because of a lack of policy responses.

In summary, the major conclusion of this study is that institutional quality is tied to digital adoptions and TFP directly and to HC indirectly. The indirect effect of HC on IQ works via DA directly and via CO indirectly (through TFP). The findings of the study have implications for practitioners and policymakers in public administration. The central lesson for an administration wishing to experience the lasting benefits of human capital and digital strategies is to think and act proactively. Rethinking and reorientation of strategies toward digital transformation and promotion of creative industries can not only bring economic effects but also reduce the administrative burden. Leveraging digital

transformation and the creative industries and services sectors can give a large push to TFP, which can further enhance IQ. It is this strengthening of institutional quality that will boost EG. Our results do not specifically pinpoint the exact mechanism through which institutional strengths can be translated into economic growth. Therefore, more research on this issue is needed.

Endnotes

1. This fit index is called RMSEA and is considered to be sensitive to the number of estimated parameters in the model.

2. Studies (Fan, Thompson and Wang 1999) point out that CFI is least affected by sample size and works well even when the sample size is small (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007).

3. The digital divide implies the divide that exists between those who have access to ICTs and those who are devoid of them (NTIA 1999). It has been pointed out in studies (Choudrie, Grey and Tsitsianis 2005, Helbig, Ramón, Gil-García and Ferro 2009) that the digital divide affects e-governance initiatives negatively.

References

Accenture (2017), Digital Adoption Report,

https://www.accenture.com/t20170206t201908z w /us-en/_acnmedia/pdf-42/accenture- digital-adoption-report.pdf

Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson and J.A. Robinson (2005), Institutions as the Fundamental Cause of Long- Run Growth, in Aghion, P. and S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth, Elsevier, North-Holland, Chap. 6.

Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson, J. Ronbinson and Y. Tchaichoroen (2003), Institutional Causes, Macroeconomic Symptoms, Volatility, Crises, and Growth, Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1): 49–123.

Bahrini, R. and A. Qaffas (2019), Impact of Information and Communication Technology on Economic Growth: Evidence from Developing Countries, Economies, 7(1): 1–13, https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7010021.

Barrett, P. (2007), Structural Equation Modelling: Adjudging Model Fit, Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5): 815-824.

Beirne, J. and P. Panthi (2022), Institutional Quality and Macro-Financial Resilience in Asia, ADBI Working Paper 1336, Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute, https://doi.org/10.56506/ YVOO4040

Bekana, D.M. (2020), Innovation and Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Why Institutions Matter? An Empirical Study Across 37 Countries, https://doi.org/10.1177% 2F0976747920915114

Benhabib, J. and M.M. Spiegel (1994), The Role of Human Capital in Economic Development Evidence from Aggregate Cross-Country Data, The Journal of Monetary Economics, 34(2): 143–173.

Bodman, P. and T. Le (2013), Assessing the Roles that Absorptive Capacity and Economic Distance Play in the Foreign Direct Investment-Productivity Growth Nexus, Applied Economics, 45(8): 1027–1039.

Bye, B. and T. Faehn (2021), The Role of Human Capital in Structural Change and Growth in an Open Economy: Innovative and Absorptive Capacity Effects, The World Economy, https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13184

Chiemeke, S.C. and O.M. Imafidorz (2020), An Assessment of the Impact of Digital Technology Adoption on Economic Growth and Labor Productivity in Nigeria, Economic Research and Electronic Networking, 21: 103–128, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11066-020-09143-7

Choudrie, J., S. Grey and N. Tsitsianis (2010), Evaluating the Digital Divide: The Silver Surfer’s Perspective’, Electronic Government, An International Journal, 7(2): 148–167.

Crespi, G. and P. Zuñiga (2010), Innovation and Productivity: Evidence from Six Latin American Countries, IDB Working Paper Series, No. IDB-WP-218.

Crowley, S.L. and X. Fan (1997), Structural Equation Modelling: Basic Concepts and Applications in Personality Assessment Research, Journal of Personality Assessment, 68(3): 508-531.

Diamantopoulos, A. and J.A. Siguaw (2000), Introducing LISREL, London: Sage Publications. Dias, J. and E. Tebaldi (2012), Institutions, Human Capital, and Growth: The Institutional

Mechanism, Structural Change, and Economic Dynamics, 23(3): 300-312, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2012.04.003.

Eichler, M. (2007), Granger Causality and Path Diagrams for Multivariate Time Series, Journal of Econometrics, 137(2)334–353, doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2005.06.032

Falk, M. and F. Biag (2015), Empirical Studies on the Impacts of ICT usage in Europe, Institute for Prospective Technological Studies Digital Economy Working Paper 2015/14.

Fan, X., B. Thompson and L. Wang (1999), Effects of Sample Size, Estimation Methods, and Model Specification on Structural Equation Modelling Fit Indices, Structural Equation Modelling, 6(1): 56-83.

Finger, G. (2007), Digital Convergence and Its Economic Implications, Development Bank of Southern Africa.

Florida, R., C. Mellander and K. Stolarick (2008), Inside the Black Box of Regional Development— Human Capital, The Creative Class, and Tolerance, Journal of Economic Geography, 8(5), 615–649. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn023

Foster, A.D. and M.R. Rosenzweig (2010), Microeconomics of Technology Adoption, Annual Review of Economics, 2: 395–424, doi:10.1146/annurev.economics.102308.124433.

Ghulam, M. (2012), Human Capital, Governance, and Productivity in Asian Economies, Job Market Paper, https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=res_phd_ 2013&paper_id=213, (referred on 19/11/2014).

Glaeser, E.L., R. La Porta, F. Lopes-de-Silanes and A. Shleifer (2004), Do Institutions Cause Growth? Journal of Economic Growth, 9(1): 271–303.

Gorodnichenko, Y. and G. Roland (2010), Culture, Institutions, and the Wealth of Nations, NBER Working Paper Series, No. 16368.

Hall, B.H. (2011), Innovation and Productivity, NBER Working Paper Series, No. 17178.

Hall, R.E. and C.I. Jones (1999), Why Do Some Countries Produce So Much More Output Per Worker Than Others? The Quarterly Journal of Economics,114 (1): 83–117.

Helbig, N., J. Ramón Gil-García and E. Ferro (2009), Understanding the Complexity of Electronic Government: Implications from the Digital Divide Literature, Government Information Quarterly, 26(1): 89-97.

Hooper, D., J. Coughlan and M. Mullen (2007), Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit, The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods,6(1): 53-60, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254742561_Structural_Equation_Modelling_Guide lines_for_Determining_Model_Fit.

Hu, L.T. and P.M. Bentler (1999), Cut-off Criteria for Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives, Structural Equation Modelling, 6(1): 1-55.

Isaksson, A. (2007), Determinants of Total Factor Productivity: A Literature Review, UNIDO Research and Statistics Branch Staff Working Paper, No. 02/2007.

Jankauskas, V. and J. Šeputienė (2007), The Relation between Social Capital, Governance and Economic Performance in Europe, Business: Theory and Practice, VIII(3): 131-138.

Kaasa, A. (2016), Social Capital, Institutional Quality, and Productivity: Evidence from European Regions, Economics and Sociology, 9(4): 11-26, DOI: 10.14254/2071-789X.2016/9-4/1

Knack, S. and P. Keefer (1995), Institutions and Economic Performance: Cross-country Tests using Alternative Institutional Measures, Economics and Politics, 7(3): 207–227.

Lipset, S.M. (1960), Political Man, Doubleday Company, Inc., NY, Available at: http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=23560876.

Mauro, P. (1995), Corruption and Growth, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(3): 681–712.

Min, J. and D.P. Mishra (2010), Analysing the Relationship between Dependent and Independent Variables in Marketing: A Comparison of Multiple Regression with Path Analysis, Innovative Marketing, 6(3):113-120, https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/business-fp/228

National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) (1999), Falling Through the Net III: Defining the Digital Divide, U.S. Department of Commerce, Washington DC.

Nelson, R.R. and E.S. Phelps (1966), Investment in Humans, Technological Diffusion and Economic Growth, American Economic Review, 56(1/2): 69–75.

North, D.C. (1990), Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance, Cambridge University Press, New York.

North, D.C. and R.P. Thomas (1973), The Rise of the Western World: A New Economic History,

Cambridge University Press.

Nwankwo, A.O. (2018), Harnessing the Potential of Nigeria’s Creative Industries: Issues, Prospects, and Policy Implications, Africa Journal of Management, 4(4): 469–487, https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2018.1522170.

Peters, B., H. Lööf and N. Janz (2003), Firm-Level Innovation and Productivity: Is there a Common Story across Countries? ZEW Discussion Papers, pp. 3-26.

Rodrik, D., A. Subramanian and F. Trebbi (2004), Institutions Rule the Primacy of Institutions Over Geography and Integration in Economic Development, Journal of Economic Growth, 9(2): 131–165.

Saniee, I, S. Kamat, S. Prakash and M. Weldon (2017), Will Productivity Growth Return in the New Digital Era?, Bell Labs Technical Journal, 20: 1-18, https://doi.org/10.15325/BLTJ. 2017.2714819

Sayes, E. (2011), Economic and Social Determinants of Productivity; Balancing Economic and Social Explanations, Paper presented at the Sociological Association of Aotearoa (NZ) Annual Conference 2011.

Sharpe, A. (2004), Exploring the Linkages between Productivity and Social Development in Market Economies, Centre for the Study of Living Standards, CSLS Research Report, No. 2004-02.

Skare, M. and D.R. Soriano (2021), How Globalization is Changing Digital Technology Adoption: An International Perspective, Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 6(4): 222-233.

Smith, A. (1776), An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, the Pennsylvania State University, Electronic Classics Series (2005), Jim Manis, Faculty Editor, Hazleton, PA. Available at: http://www2.hn.psu.edu/faculty/jmanis/adamsmith/Wealth-Nations.pdf.

Steiger, J.H. (1990), Structural Model Evaluation and Modification, Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2): 214-12.

Syverson, C. (2011), What Determines Productivity? Journal of Economic Literature, 49(2): 326- 365.

Tabachnick, B.G. and L.S. Fidell (2007), Using Multivariate Statistics (5th Ed.), New York: Allyn and Bacon.

Yamamura, E. and I. Shin (2012), Heterogeneity, Trust, Human Capital, and Productivity Growth: A Decomposition Analysis, Journal of Economics and Econometrics, 55(2), 51-77.

R.B.R.R. Kale Memorial Lectures at Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics

+ 1937 Modern Tendencies in Economic Thought and Policy by V.G. Kale 1938 The Social Process by G.S. Ghurye

- 1939 Federation Versus Freedom by B.R. Ambedkar

+ 1940 The Constituent Assembly by K.T. Shah

- 1941 The Problem of the Aborigines in India by A.V. Thakkar

- 1942 A Plea for Planning in Cooperation by V.L. Mehta 1943 The Formation of Federations by S.G. Vaze

+ 1944 Economic Policy by John Mathai

+ 1945 A Statistical Approach to Vital Economic Problems by S.R. Deshpande

+ 1946 India’s Sterling Balances by J.V. Joshi

- 1948 Central Banking in India: A Retrospect by C.D. Deshmukh

- 1949 Public Administration in Democracy by D.G. Karve 1950 Policy of Protection in India by R.L. Dey

1951 Competitive and Cooperative Trends in Federalism by M. Venkatrangaiya 1952 The Role of the Administrator: Past, Present and Future by A.D. Gorwala

+ 1953 Indian Nationalism by Laxmanshastri Joshi

1954 Public Administration and Economic Development by W.R. Natu

+ 1955 Some Thoughts on Planning in India by P.C. Mahalanobis

1956 Reflections on Economic Growth and Progress by S.K. Muranjan 1957 Financing the Second Five-Year Plan by B.K. Madan

+ 1958 Some Reflections on the Rate of Saving in Developing Economy by V.K.R.V. Rao 1959 Some Approaches to Study of Social Change by K.P. Chattopadhyay

- 1960 The Role of Reserve Bank of India in the Development of Credit Institutions by B. Venkatappiah

1961 Economic Integration (Regional, National and International) by B.N. Ganguli 1962 Dilemma in Modern Foreign Policy by A. Appadorai

- 1963 The Defence of India by H.M. Patel

- 1964 Agriculture in a Developing Economy: The Indian Experience (The Impact of Economic Development on the Agricultural Sector) by M.L. Dantwala

+ 1965 Decades of Transition – Opportunities and Tasks by Pitambar Pant

- 1966 District Development Planning by D.R. Gadgil

1967 Universities and the Training of Industrial Business Management by S.L. Kirloskar 1968 The Republican Constitution in the Struggle for Socialism by M.S. Namboodripad 1969 Strategy of Economic Development by J.J. Anjaria

1971 Political Economy of Development by Rajani Kothari

+ 1972 Education as Investment by V.V. John

1973 The Politics and Economics of “Intermediate Regimes” by K.N. Raj 1974 India’s Strategy for Industrial Growth: An Appraisal by H.K. Paranjape 1975 Growth and Diseconomies by Ashok Mitra

1976 Revision of the Constitution by S.V. Kogekar

1977 Science, Technology and Rural Development in India by M.N. Srinivas 1978 Educational Reform in India: A Historical Review by J.P. Naik

1979 The Planning Process and Public Policy: A Reassessment by Tarlok Singh

- Out of Stock + Not Published No lecture was delivered in 1947 and 1970

R.B.R.R. Kale Memorial Lectures at Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics

| 1980 | Problems of Indian Minorities by Aloo J. Dastur | |

| 1981 | Measurement of Poverty by V.M. Dandekar | |

| 1982 | IMF Conditionality and Low Income Countries by I.S. Gulati | |

| * | 1983 | Inflation – Should it be Cured or Endured? by I.G. Patel |

| 1984 | Concepts of Justice and Equality in the Indian Tradition by M.P. Rege | |

| 1985 | Equality of Opportunity and the Equal Distribution of Benefits by Andre Beteille | |

| 1986 | The Quest for Equity in Development by Manmohan Singh | |

| 1987 | Town and Country in Economy in Transition by K.R. Ranadive | |

| 1988 | Development of Development Thinking by Sukhamoy Chakravarty | |

| 1989 | Eighth Plan Perspectives by Malcolm S. Adiseshiah | |

| 1990 | Indian Public Debt by D.T. Lakdawala | |

| 1991 | Public Versus Private Sector: Neglect of Lessons of Economics in Indian Policy Formulation by B.S. Minhas | |

| 1992 | Agricultural and Rural Development in the 1990s and Beyond: What Should India Do and Why? by V. Kurien | |

| 1993 | An Essay on Fiscal Deficit by Raja J. Chelliah | |

| 1994 | The Financing of Higher Education in India by G. Ram Reddy | |

| 1995 | Patenting Life by Madhav Gadgil | |

| 1996 | Constitutional Values and the Indian Ethos by A.M. Ahmadi | |

| 1997 | Something Happening in India that this Nation Should be Proud of by Vasant Gowariker | |

| 1998 | Dilemmas of Development: The Indian Experience by S. Venkitaramanan | |

| 1999 | Post-Uruguay Round Trade Negotiations: A Developing Country Perspective by Mihir Rakshit | |

| 2000 | Poverty and Development Policy by A. Vaidyanathan | |

| 2001 | Fifty Years of Fiscal Federalism in India: An Appraisal by Amaresh Bagchi | |

| + | 2002 | The Globalization Debate and India’s Economic Reforms by Jagdish Bhagwati |

| 2003 | Challenges for Monetary Policy by C. Rangarajan | |

| + | 2004 | The Evolution of Enlightened Citizen Centric Society by A.P.J. Abdul Kalam |

| 2005 | Poverty and Neo-Liberalism by Utsa Patnaik | |

| 2006 | Bridging Divides and Reducing Disparities by Kirit S. Parikh | |

| 2007 | Democracy and Economic Transformation in India by Partha Chatterjee | |

| 2008 | Speculation and Growth under Contemporary Capitalism by Prabhat Patnaik | |

| 2009 | Evolution of the Capital Markets and their Regulations in India by C.B. Bhave | |

| + | 2010 | Higher Education in India: New Initiatives and Challenges by Sukhadeo Thorat |

| 2011 | Food Inflation: This Time it’s Different by Subir Gokarn | |

| 2012 | Innovation Economy: The Challenges and Opportunities by R.A. Mashelkar | |

| + | 2014 | World Input-Output Database: An Application to India by Erik Dietzenbacher Subject |

| + | 2015 | Global Economic Changes and their implications on Emerging Market Economies by |

| + | 2016 | Raghuram Rajan SECULAR STAGNATION-Observations on a Recurrent Spectre by Heinz D. Kurz |

| + | 2017 2019 | Role of Culture in Economic Growth and in Elimination of Poverty in India by N. R. Narayana Murthy Central Banking: Retrospect and Prospects by Y. Venugopal Reddy |

| + | 2020 | Introduction to Mechanism Design by Eric Maskin |