Social Capital and Human Well-Being: A Comparative Study of BRICS Countries

December 2023 | Shiv Kumar

I Introduction

In the past 25-30 years, Putnam (1993, 1995), Coleman (1988, 1990) and World Bank [Narayan (1997), Collier (1998), Grootaert (1999) and Knack (1999, 2002)] explored the term social capital in the context of political participation, human capital formation, and economic development respectively. Glaeser, et. al. (2002) presented an economic approach to social capital and Okunmadewa, et. al. (2007) studied the effects of social capital on rural poverty. Social capital theorists claim that social capital has positive impacts on various aspects of societal life, such as economic well-being, health, crime rates, educational achievement, and adolescent development (Woolcock 1998). Thus, the main objective of this paper is to examine the inter-linkage between social capital and human well-being in the five BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. The paper is divided into six sections. Following the introduction, the second section presents the data sources and methodology. The concept of social capital with literature review is explained in section three. Section four measures the social capital in five BRICS countries. Section five examines the impact of social capital on human well-being and the final section concludes the paper.

II Data Sources and Methodology

BRICS represent some of the major emerging economies of the world, covering over 40 per cent of the world population. Therefore, the study is based on data collected from 8599 individuals in five BRICS countries by World Values Survey (WVS) wave 6 (2010-14). The WVS is a global research project that explores people’s values and beliefs, how they change over time and what social and political impact they have. The present paper is based on the individual responses for21 questions out of a total set of 258 common questions used in WVS in all countries. The collected data are analyzed by using correlation, regression, t-test, F test, one-way ANOVA, multiple comparison of means test by applying post Hoc tests in addition to descriptive statistics.

III The Concept of Social Capital: A Literature Review and Research Gaps

Social capital has been widely discussed across the social sciences in recent years. One of the pioneers in the study of social capital is Hanifan (1920) who argued that “social capital refers to those tangible assets that count for most in the daily lives of people, namely, goodwill, fellowship, sympathy, and social intercourse among the individuals and families who make up a social unit.” Others include Jacobs (1961), Bourdieu and Passeron (1977), Loury (1977) [As cited in Woolcock 1998], and Meehan, et. al. (1978). Bourdieu (1984, 1986) developed the concept of social capital during the 1970s and 1980s, but it attracted much less attention than other areas of his social theory. In the past 25-30 years, Putnam (1993, 1995) and Coleman (1988, 1990) are credited with bringing the term “social capital” to prominence.

In the literature, social capital is often defined as a sociological variable, i.e., referring to the relationships between people. From this perspective social capital is relational, not something owned by any individual, but rather something shared in common. However, there is a perspective that social capital stands for the ability of actors to secure benefits by virtue of membership in networks or other social structures (Portes 1998). Thus, it is possible to distinguish ‘individual’ and ‘group’ social capital. Individual social capital, sometimes referred to as ‘social network capital’, can be defined as the set of social attributes possessed by an individual – including charisma, contacts and linguistic skill – that increase the returns to that individual in his or her dealings with others. Community-level ‘group’ social capital is defined as the set of social resources of a community that increases the welfare of that community (Glaeser, et. al. 2002). Bezemer, et. al. (2004) used the term ‘relational capital’ for individual social capital, and ‘social network’ or ‘communal social capital’ for group social capital. Knack (1999, 2002) differentiated social capital as government social capital and civil social capital. He defined government social capital as the institutions, the rule of law, and the civil liberties that influence people’s ability to cooperate for mutual benefit; and civil social capital as the common values, norms, informal networks, and associational memberships that affect the ability of individuals to work together to achieve common goals. Grafton and Knowles (2004) distinguished between civic social capital and public institutional social capital, with the latter being defined

by measures of corruption and democracy. Grootaert (1999) talked about a macro level of social capital which includes institutions such as government, the rule of law, civil and political liberties, etc. These notions of government, public institutional and macro social capital are identical to formal institutions. Collier (1998) noted that many people restrict the term “social capital” to civil social capital. Thus, for the individual level study to find the inter-linkage between social capital and human well-being, it seems wise to restrict the definition of social capital to civil social capital.

IV Measurement of Social Capital in Brics

Trust and trustworthiness increase the chances of exchange among people without written contractual obligations. Instead people rely on expectations of mutual obligation, honesty, reciprocity, mutual respect, and helpfulness (Narayan 1997). Thus, in the study, generalized trust among individuals is taken as the proxy indicator of social capital. To measure generalized trust, individuals were asked in World Values Survey about seven questions (Appendix 1).

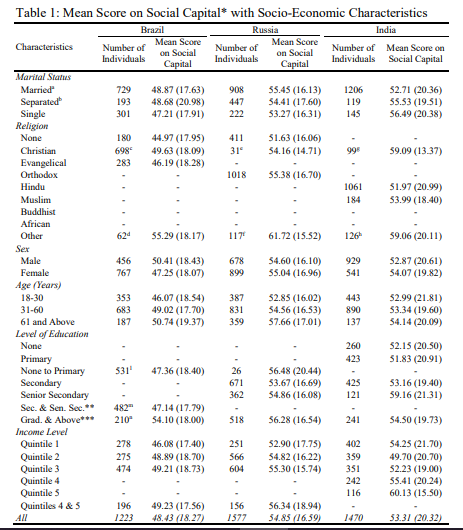

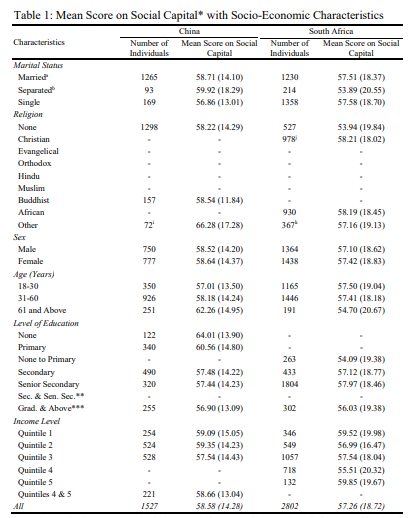

To construct the social capital index, the individual scores on these seven questions are added and the resultant score is rescaled from 0 to 100 where 0 represents the lowest level of social capital. For all the BRICS countries together, mean score for individuals on the social capital index is found to be 51.92 points out of maximum possible 100 points with standard deviation 18.55.For the countries of Brazil, Russia, India and China, there is no significant difference between mean scores on social capital for individuals with different marital status; for South Africa, however, social capital is significantly high for married and single individuals as compared to divorced/separated/widowed individuals (Table 1).

It is observed in the analysis of data that social capital is related to the religious dimension of individuals since social capital is found to be different among different religions. In Brazil, for Christians the mean social capital score of 49.63 points is significantly higher as compared to the individuals with no religion (Table 1). For the individuals with Buddhist, Muslim, Spiritista, Espirit, Candombl, Umbanda, Esoterism, Occult, and other not specific religion in Brazil, the mean social capital score is observed as 55.29 points which is significantly different from the mean score for individuals with no religion and the Evangelical individuals. In Russia, the mean score of social capital for the individuals with no religion is calculated as 51.63 points, for individuals with Orthodox religion as 55.38 points and for the individuals with Buddhist, Muslim, or other not specific religion as 61.72 points. All these mean scores are found to be significantly different from each other. In India, the mean social capital score 51.97 points for Hindu individuals is calculated as the significantly lowest as compared to the individuals with Christian, Buddhist, Orthodox, and other not specific individuals where it is found to be more than 59 points. For Protestant, Roman Catholic, Muslim, Taoism, Protestant Fundam, Ancient Cults, or other not specific religion in China, the mean social capital score is observed as 66.28 points which is significantly high as compared to the individuals with no religion and the individuals with Buddhist religion. In South Africa, for Christians the social capital score is 58.21, for African religion individuals social capital score is 58.19 and for Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, Orthodox, and other not specific religious group, the mean social capital score is 57.16. All these scores are significantly high for the individuals with no religion where it is observed as 53.94 points.

Notes: *Generalized trust among individuals (measured by trustworthiness, and trust in family, neighbourhood, personally known people, people met for the first time, people of another religion and people of another nationality) is taken as the proxy indicator of social capital. Individual scores on these seven ingredients of trust are added and the resultant score is rescaled from 0 to 100 to construct the Social Capital Index (SCI) where 0 represents the lowest level of social capital; ** Sec. & Sen. Sec. = Secondary and Senior Secondary; *** Grad.

= Graduation.

- Includes married, and living together as married.

- Includes divorced, separated, and widowed.

- Includes Protestant, and Roman Catholic.

- Includes Buddhist, Muslim, Spiritista, Espirit, Candombl, Umbanda, Esoterism, Occult, and other not specific.

- Includes Jew, Protestant, Roman Catholic.

- Includes Buddhist, Muslim, and other not specific.

- Includes Christian, Jew, Protestant, and Roman Catholic.

- Includes Buddhist, Orthodox, and other not specific.

- Includes Protestant, Roman Catholic, Muslim, Taoism, Protestant Fundam, Ancient Cults, and other not specific.

- Includes Jehovah Witnesses, Jew, Pentecostal, Protestant, and Roman Catholic.

- Includes Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, Orthodox, and other not specific.

- Includes No Formal Education, Incomplete Primary School, and Complete Primary School.

- Includes Incomplete Secondary School: Technical/Vocational Type, Complete Secondary School: Technical/Vocational Type, Incomplete Secondary School: University-Preparatory Type, and Complete Secondary School: University-Preparatory Type.

- Includes Some University-Level Education: Without Degree, and Some University-Level Education: With Degree.

Figures in parentheses are standard deviations.

Source: Calculated from World Values Survey, Wave 6 (2010-14) Data.

The absolute mean difference of social capital scores between male and female respondents is 3.16 in Brazil which is statistically significant (Table 1). However, for all other BRICS countries, this difference in mean score is found to be statistically insignificant. It is also observed that in Brazil, Russia and China the mean social capital score has increased significantly with the rise in age of individuals. On the other hand, mean social capital score is rising with the age in India and is falling with the age in South Africa but these mean differences are not statistically significant.

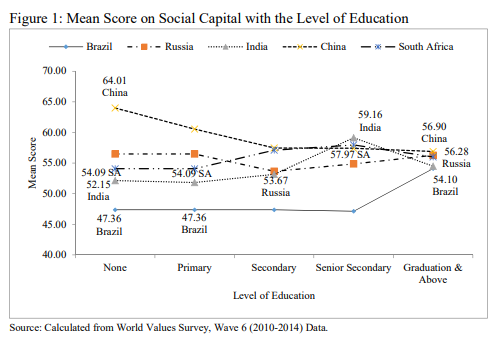

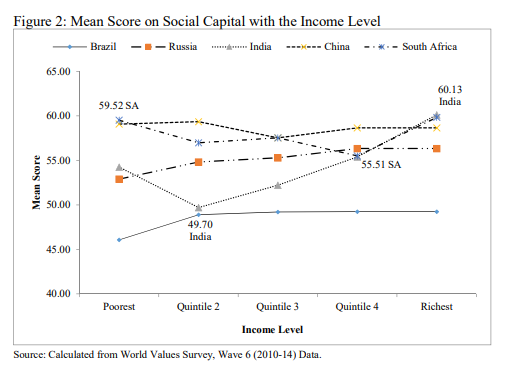

In the study, social capital mean scores are tabulated with the level of education and income of the individuals and it is found that as the level of education rises, the score on social capital index rises at the significant level except for China where it decreased from 64.01 points to 56.90 points (Figure 1 and Table 1). It is also observed that in India as the level of income of the individuals rises the mean social capital also rises at the significant level, but the reverse trend has been found in South Africa where it decreases from 59.52 points to 55.51 points (Figure 2 and Table 1). In other three countries of BRICS – Brazil, Russia and China – the mean social capital score has not significantly related with the level of income of the individuals.

II Social Capital and Human Well-Being

The main objective of this study is to analyze the impact of social capital on human well-being of individuals. The individual well-being is hypothesized to be influenced by the independent variables included in the equation below:

Wi = a + b1SCi + b2HCi + b3Yi + b4SXi + b5AGi + ui …(1) Where, Wi = Index of Human Well-Being of Individual i

SCi = Individual Endowment of Social Capital HCi = Individual Endowment of Human Capital Yi = Household Income Level

SXi = Gender of Respondent AGi = Age of Respondent

ui = Error Term

- Variable Definitions

- Human Well-Being: Following the methodology of Grootaert (1999), human well-being index is constructed by adding individual scores on seven different aspects namely, happiness in life, health condition, satisfaction in life, freedom of choice, financial satisfaction, citizenship proud, and the extent of savings (Appendix 2). The responses on these seven aspects are added and then rescaled from 0 to 100 to measure well-being of individuals where 0 represents the lowest level of human well-being.

- Social Capital: Generalized trust among individuals (measured by trustworthiness, trust in family, neighbourhood, personally known people, people met for the first time, people of another religion and people of another nationality) is taken as the proxy indicator of social capital. Individual scores on these seven ingredients of trust are added and the resultant score is rescaled from 0 to 100 to construct the Social Capital Index (SCI) where 0 represents the lowest level of social capital.

- Human Capital: The human capital variable is measured as the highest education level attained by the individual.

- Income: Level of income is calculated by asking individual counting all wages, salaries, pensions, and other incomes, in which group the individual considers his/her household in the ten income groups, where the first decile is the lowest income group.

- Gender of Respondent: A dummy variable is used for the gender of respondent (D=1 if male, D=0 if otherwise).

- Age of Respondent: Age of respondent is measured in years.

(ii) Results and Discussion

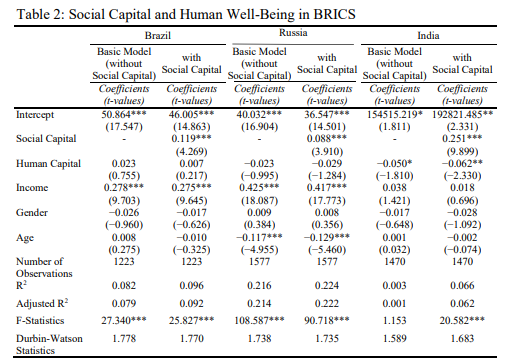

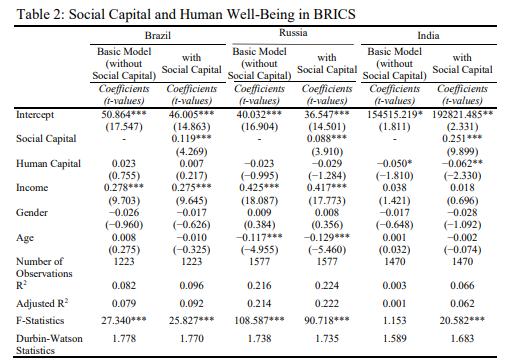

In Table 2 the first column under each country shows the basic model of individual well-being without social capital. This model shows that 21.4 per cent, 19.9 per cent, 15.8 per cent, 7.9 per cent and 0.1 per cent of the variations in well-being of individuals are explained by the specified human capital, income and demographic factors of the individuals in Russia, South Africa, China, Brazil and India respectively. In specific terms, in China and South Africa, higher level of education of the individual significantly improves the well-being (coefficients

0.373 and 0.113 respectively). On the contrary, in India, human capital has the negative impact on human well-being which is more significantly explained by the income of the household (coefficient 0.038). It is observed that in Brazil, Russia and South Africa, the level of income, with coefficients 0.278, 0.425 and 0.403 respectively, is the greatest contributor in human well-being. It is also observed that South Africa is the only country among five BRICS countries where both human capital and income have the positive and significant impact on human well- being.

Notes: Figures in parentheses are t-values. ***significant at one per cent, **significant at five per cent and

*significant at 10 per cent. The dependent variable is the well-being of individuals. Source: Computed from World Values Survey, Wave 6 (2010-14) Data.

The social capital variable is introduced in the second column of Table 2 under each country. The inclusion of this variable led to improvement in the adjusted R2 from 0.079 to 0.092 in Brazil, 0.214 to 0.222 in Russia, 0.001 to 0.062 in India, 0.158 to 0.188 in China and 0.199 to 0.200 in South Africa. The analysis of data in Table 2 reveals that in all the five BRICS countries, social capital significantly as well as positively influenced the human well-being with the coefficients of 0.119, 0.088, 0.251, 0.176, and 0.033 in Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa respectively. It is also found that in South Africa, along with human capital and income, social capital significantly influences the well-being status of individuals. The results in Table 2 also show that household well-being is not influenced by the gender of the individual whereas the age of the individual has a dual effect. In Russia, the age of the individual has a negative impact, and in China it has a positive impact on human well-being.

II Conclusion

In the present paper, the impact of social capital on human well-being is studied on the basis of field survey data collected by World Values Survey, Wave 6 (2010- 14) in five BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. In the study, generalized trust among individuals is taken as the proxy indicator of

social capital. It is found in the study results, that in all the five BRICS countries, social capital positively influenced human well-being and thus, is an important instrument to raise the well-being of individuals. Thus, with the many positive benefits of social capital, it is concluded that increasing levels of this dynamic form of capital can help individuals, households and communities to become more sustainable. Finally, the study suggests that development programmes should integrate social capital as an essential element and like human capital, the investments in the social capital should also be made.

References

Bezemer, D.J., U. Dulleck and P. Frijters (2004), Social Capital, Creative Destruction and Economic Growth, Working/Discussion Paper No. 186a, School of Economics and Finance, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane.

Bourdieu, P. (1984), Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Translated by Richard Nice, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

———- (1986), The Forms of Capital, in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, J.G. Richardson (Ed.), Greenwood Press: Westport, Connecticut, pp. 241-258.

Bourdieu, P. and J.C. Passeron, (1977), Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, Translated by Richard Nice, Sage Publications, London.

Coleman, J.S. (1988), Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital, American Journal of Sociology, 94(Supplement): S95-S120.

———- (1990), Foundations of Social Theory, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Collier, P. (1998), Social Capital and Poverty, Social Capital Initiative Working Paper No. 4, Social Development Department, The World Bank, Washington D.C.

Glaeser, E.L., D.I. Laibson and B. Sacerdote (2002), An Economic Approach to Social Capital, The Economic Journal, 112(483): F437-F458.

Grafton, R.Q. and S. Knowles (2004), Social Capital and National Environmental Performance: A Cross-Sectional Analysis, Journal of Environment and Development, 13(4): 336-370.

Grootaert, C. (1999), Social Capital, Household Welfare and Poverty in Indonesia, Local Level Institutions Working Paper No. 6, Social Development Department, The World Bank, Washington D.C.

Hanifan, L.J. (1920), The Community Centre, Silver Burdett and Company, Boston.

Jacobs, J. (1961), The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Random House, New York. Knack, S. (1999), Social Capital, Growth and Poverty: A Survey and Extensions, Social Capital

Initiative Working Paper No. 7, Social Development Department, The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

———- (2002), Social Capital, Growth and Poverty: A Survey of Cross-Country Evidence, in The Role of Social Capital in Development: An Empirical Assessment, C. Grootaert and T. van Bastelaer (Eds.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Loury, G.C. (1977), A Dynamic Theory of Racial Income Differences, in Women, Minorities and Employment Discrimination, P.A. Wallace and A. LaMund (Eds.), Lexington Books, Lexington, Massachusetts, pp. 153-188.

Meehan, E.J., A.C. Reilly and T. Ramey (1978), In Partnership with People: An Alternative Development Strategy, Inter-American Foundation, Rosslyn.

Narayan, D. (1997), Voices of the Poor: Poverty and Social Capital in Tanzania, World Bank, Washington D.C.

Okunmadewa, F.Y., S.A. Yusuf and B.T. Omonona (2007), Effects of Social Capital on Rural Poverty in Nigeria, Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences, 4(3): 331-339.

Portes, A. (1998), Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology, Annual Review of Sociology, 24: 1-24.

Putnam, R.D. (1993), The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life, The American Prospect, 4(13): 35-42.

Putnam, R.D. (1995), Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital, Journal of Democracy, 6(1): 65-78.

Woolcock, M. (1998), Social Capital and Economic Development: Towards a Theoretical Synthesis and Policy Framework, Theory and Society, 27(2): 151-208.