Educational Outcomes of the Tribal Students of Kerala – Exploring the Potential of Cultural Capital

March 2024 | Parvathy P. and Kavitha A.C.

Abstract

Scheduled tribes constitute 1.45 per cent of the total population of Kerala as per 2011 Census. Though Kerala has made significant strides in the field of education, tribal students in the state fall behind the non-tribal students as evident from several indicators such as lower rates of enrolment, higher drop-out rates and lower pass percentage at various levels of education. Lower pass percentage of tribal students in the qualifying examinations (58.01 per cent for the tribal students visà-vis the state overall pass percentage of 85.56 per cent in 2020-2021) poses a significant barrier to pursue graduation courses. Hence, an attempt is made to assess the role of cultural capital in determining the educational outcomes of the students belonging to various castes. A survey of the students enrolled in colleges revealed differences in the extent of cultural capital possessed by tribal and non-tribal students as evident from the differences in the education levels of parents which are corroborated by the results of Kruskal Wallis test. Cultural capital deficit places the tribal students at a disadvantage in various fields such as language proficiency and their ability to critically appreciate arts and literature. Inadequate cultural capital base of tribal students has adversely affected their educational outcomes.

Key Words

Cultural capital, Tribal students, Educational outcomes.

I Introduction

Capital, acknowledged as a productivity enhancing factor has evolved over the years so as to incorporate multiple dimensions such as physical capital, natural capital, human capital, financial capital and social capital. One of the recent additions to the concept of capital has been ‘Cultural Capital’ which is often regarded as a critical factor producing enhanced educational outcomes.

The concept of cultural capital has been introduced by Pierre Bourdieu (1986). Cultural capital may be broadly defined as a community’s embodied cultural skills and values, in all their community-defined forms, inherited from the community’s previous generation, undergoing adaptation and extension by current members of the community, and desired by the community to be passed on to its next generation. Cultural capital is of three types: embodied, objectified and institutionalized. Embodied cultural capital refers to quality of a person’s mind or body such as skill, taste, accent, posture, mannerism, etc., which cannot be transmitted instantaneously by gift or bequest or by purchase or exchange. It functions as a symbolic capital as it is unrecognized as a capital but acknowledged as a competence. Objectified capitals are material belongings that have cultural significance. Cultural capital in the objectified state is in the form of cultural goods such as books, pictures, dictionaries, instruments, etc., and can be transmitted both materially and symbolically. Institutionalized cultural capital is symbols of authority, credentials and qualification such as the title Doctor, Advocate etc., that can give large institutionalized cultural capital. A University degree is also a powerful form of this sort of capital as it gives skill, knowledge and develops other traits. Thus, it enhances institutionalized cultural capital.

Statement of the Problem

Cultural capital is regarded as a critical factor that contributes to the educational success of an individual. In the context of disparities observed in the educational attainment among students, there is a need to identify the role played by cultural capital in influencing educational outcomes. The role of cultural capital in enhancing educational outcomes can be analysed by assessing the transmission of cultural capital across generations among the students belonging to various social classes.

Objective

- To examine the impact of cultural capital on educational attainment of the students.

Materials and Methods

A vast body of academic literature discussing the impact of cultural capital on educational attainments can be found. The core hypothesis in Cultural Reproduction Theory is that cultural capital, transferred over generations and possessed by families and individuals, is an important resource which contributes to an individual’s educational success. Educational inequalities observed among the individuals can be attributed to the differences in the critical factor cultural capital possessed by individuals (Bourdieu 1986). Unequal distribution of cultural capital leads to educational inequality at the macro level as suggested by Cultural Mobility Theory (DiMaggio 1982). It is observed that low Socio- Economic Status (SES) children have a higher return to cultural capital than high SES children (Meier and Karlson 2018). Case studies of social class differences in family-school relationships could establish that a middle class family belonging to a particular social class exhibits cultural capital higher than that of below the poverty line family belonging to the same social class (Annette and Elliot B 2003). The relationship between family SES, cultural capital and reading achievement among students in five post socialist Eastern European countries (Bulgaria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Russia) and three western countries (the US, France and Germany) based on the Programme for International Student Assessment data revealed that higher SES students possessed higher cultural capital contributing to higher educational attainment indicating an absence of East West divide (Katerina, Haram and Soo-yong 2017). Cultural capital has a positive impact on educational outcomes measured in terms of secondary school enrolment as well as grades scored as evident from the studies conducted in Croatia (Zeljko and Dukic 2016). Further it is found that parental reading behaviour affects children’s educational attainment rather than parents’ participation in cultural activities as the former reflects linguistic and cognitive skill of parents which can be transferred to their children. Parents with reading behaviour were well informed and had cultural literacy which would benefit the children by improving their schooling. Another major finding was that differences in parental cultural capital, measured by parental participation or parental reading habits are more important for children from lower and middle socio-economic backgrounds and less important for children from high socio- economic backgrounds (Graaf and Graaf 2000). Unprivileged groups certainly possess some sort of cultural capital that have no merit in the present societal structure as compared to privileged group. This results in natural exclusion of the oppressed candidates. Students in the oppressed section have to put surplus effort to reach the level of their peers. Though their parents have local knowledge and skill, traditional occupation etc., such inherited cultural capital would not be sufficient for them to be on par with upper caste students. This difference in the inherited cultural capital creates inequality in educational outcome. This necessitates affirmative action to lift the unprivileged section to ensure their representation in employment, education and politics (Syamprasad 2019).

This study seeks to examine the impact of cultural capital on the educational attainment of the students within the context of the state of Kerala, well-known for its achievements in the field of education. However, despite the appreciable track record of the state in producing better educational outcomes, the tribal population in the state has failed to excel in the field of education with the academic performance of the tribal students consistently falling behind the state average. The disparities between tribal and non-tribal students get aggravated in the field of higher education which could be evident from the enrolment and drop-out rates.

Secondary data sources such as Economic Review, Govt. of Kerala and AISHE report of Ministry of Human Resource Development are used to bring out the educational inequality across the tribal and non-tribal students within the state based on indicators such as enrolment rates, drop-out rates and pass percentage. Reckoning the disadvantaged position of the tribal students in the state especially in the field of higher education, the sample has been so selected as to include tribal and non-tribal students. A sample of 60 students comprising tribal and non-tribal students has been randomly drawn from across the colleges to examine the role of cultural capital in producing enhanced educational outcomes. In this study, parental education and their reading behaviour are taken as cultural resources that affect educational attainment, ambition and linguistic skill of students.

Kruskal Wallis test was performed to find out the extent to which the possession of cultural capital by parents and grandparents varies across the social categories. The possession of cultural capital is well reflected in the capability to nurture interests in varied fields such as language and literature, arts, music and films. Numerous statements to identify the interests, capabilities and skills demonstrated by the students in the fields of literature and arts were framed. The responses of the Scheduled Tribes (ST) and non-ST categories of students were elicited using a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 to 5 with lower end value 1 indicating strongly disagree and the higher end value 5 indicating strongly agree for the positive statements framed. Computation of mean scores based on the responses given by the students enables us to make a comparison between ST and non – ST students.

II Results and Discussion

Despite significant strides made by Kerala in the fields of education, the performance of tribal students has consistently lagged behind non-tribal students at all levels of education. This is confirmed by various indices such as enrolment rates, drop-out rates and pass percentage of tribal students vis-à-vis the non-tribal students. The drop-out ratio of tribal students at school level though is declining, is higher than the corresponding figure for the state as a whole. Drop-out ratio of the tribal students at school level stood at 1.17 per cent vis-à-vis 0.11 per cent for the state in 2019-2020 (Economic Review 2021). Though all the social groups at various levels of school education in the state performed better than the national average in the National Achievement Survey, 2017-2018, the performance of the tribal students in Kerala was below the national figure in Mathematics.

Higher secondary examination is regarded as the qualifying examination for joining degree courses. The pass percentage of the tribal students in the qualifying examination has been consistently below the state average as revealed by the data on the results of higher secondary examination for various years. In 2018-2019, the pass percentage of the tribal students was 65.71 per cent which is significantly lower than the state overall pass percentage that stood at a high of 84.28 per cent (Economic Review 2019). Though the overall pass percentage in higher secondary examinations has increased to 85.56 per cent in 2020-2021, the pass percentage of tribal students has decreased to 58.01 per cent in the same year (Economic Review 2021). The enrolment of tribal students in the field of higher education is below the national average. Gross Enrolment Ratio in higher education in India is 27.1, while for the tribal students the corresponding figure is 18 (AISHE 2019-2020). The enrolment rate of ST students in the colleges though lower in the state has been improving steadily since 2012. The enrolment of tribal students in Kerala for UG and PG courses in Arts and Science Colleges stood at 5164 and 1792 respectively in 2018-19 (Economic Review 2019). ST students constitute 2.17 per cent of the total enrolment in higher education institutes in the state (Economic Review, 2021).

Reckoning the dismal performance of the tribal students in indicators such as pass percentage at the qualifying higher secondary examinations, enrolment in various higher education courses etc., the paper seeks to analyse the role of cultural capital in determining the disadvantage experienced by the tribal students based on a sample of 60 students belonging to tribal and non-tribal students drawn from colleges in Kerala. Higher education institutes being the symbols of institutionalized cultural capital, there is a need to assess the cultural capital base of the tribal students vis-à-vis the non-tribal students.

An attempt has been made to find out the role of social categories in shaping the higher educational outcomes of the students. The language proficiency of the students as well as their yearning to pursue higher education were analysed category wise and it is interesting to observe that the tribal as well as non-tribal students had language proficiency with both the groups having a flair for mother tongue. While none of the tribal students had proficiency in a language other than mother tongue, just 4 students in non-tribal category had proficiency in mother tongue as well as English. Further it is interesting to observe that both tribal and non-tribal students have aspirations for higher education.

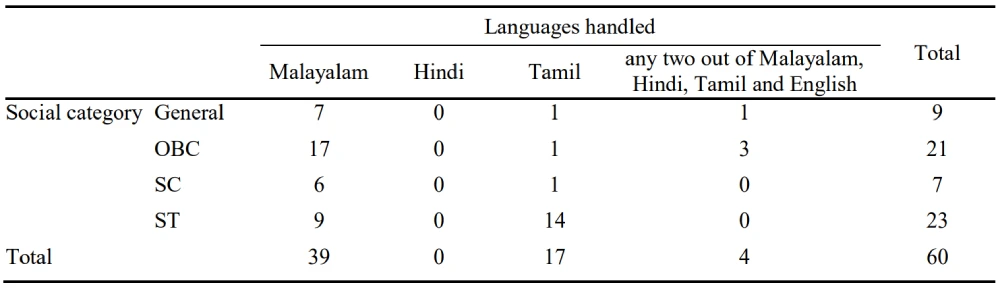

Table 1: Cross tabulation on Social Category and Language Proficiency

Source: Computed based on data from Field Survey, 2019.

Language proficiency is an indicator of the magnitude of cultural capital possessed by the students and is a strong signal of the capabilities of the students to progress academically enabling them to acquire other forms of capital such as economic capital, financial capital and social capital. An attempt was made to assess the language proficiency of the tribal and non-tribal students eliciting responses on the number of languages they can read, write and speak. It could be observed that an overwhelming number of ST students are proficient in their native tongue while a significant number of non-tribal students have proficiency in their mother tongue as well as English enabling them to make tremendous academic progress. ST students were good in handling languages like Tamil and Malayalam. But when compared to non-ST, they find difficulty in expressing their views in English (see Table 1).

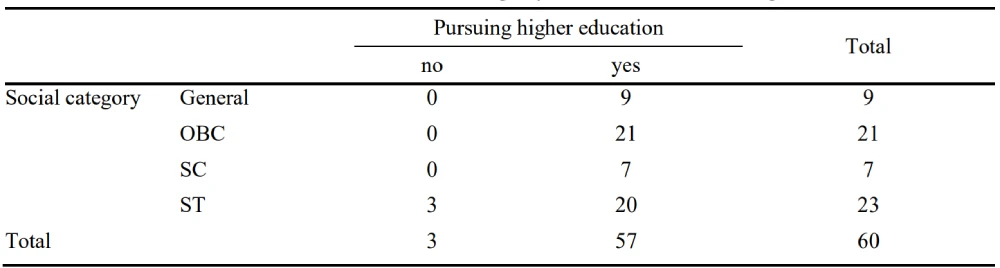

Table 2 explicitly indicates a yearning for higher education on the part of tribal and non-tribal students. However, out of 60 respondents, all the 3 respondents who are reluctant to pursue higher education belong to the tribal category.

Table 2: Cross tabulation on Social Category and Pursuit of Higher Educations

Source: Computed based on data from Field Survey, 2019.

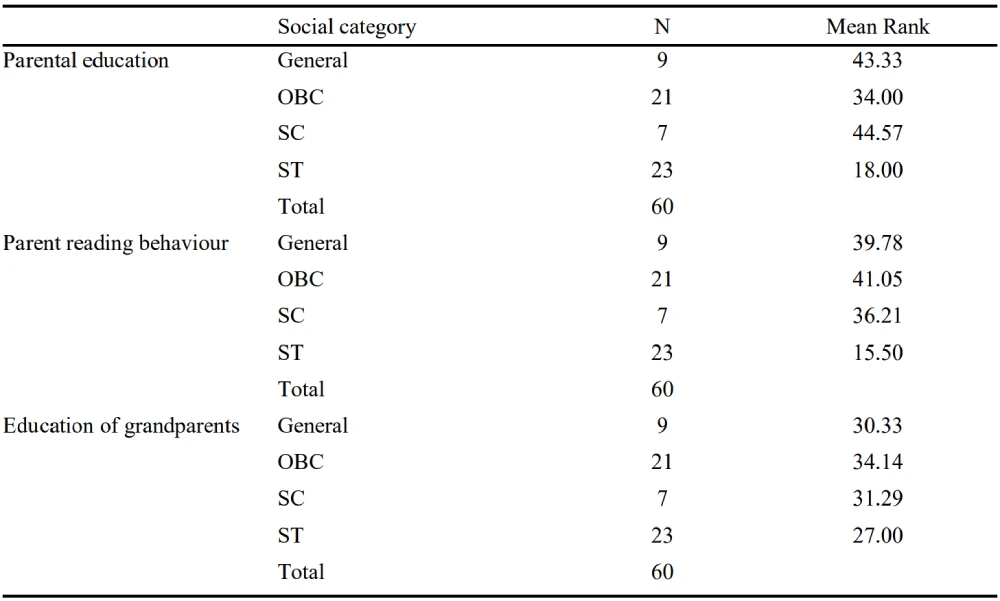

Cultural capital of the parents and grandparents of the students belonging to these categories were assessed to find out the extent to which the possession of cultural capital heritage would positively affect the higher educational outcomes of the students across tribal and non-tribal categories (see Tables 3a and 3b).

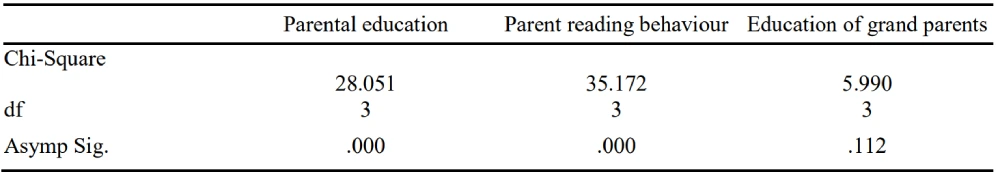

Kruskal Wallis test was performed to find out the extent to which the possession of cultural capital by parents and grandparents varies across the social categories (see Tables 3a and 3b). The cultural capital of the parents and grandparents were assessed using measures such as the educational qualifications of parents and grandparents and also the reading behaviour of the parents.

The results obtained for the parental education as well as for parental reading behaviour are statistically significant. As p value is less than 0.01, it can be stated that parental education as well as parental reading behaviour significantly differ across the social categories. The mean rank possessed by the ST category is lower than the non –ST categories such as General, OBC and SC in the case of parental education as well as parental reading behaviour. This is an obvious indication of the edge enjoyed by the non-ST students vis-à-vis the ST students in the possession of cultural capital. Besides these, a significant number of drop outs of tribal students from colleges could be observed which would pose a barrier to the accumulation of cultural capital base.

Table 3a: Cultural Capital of Parents and Grand Parents of Students across Social Categories – Mean Ranks

Source: Computed based on data from Field Survey, 2019.

Table 3b: Cultural Capital of Parents and Grand Parents of Students across Social Categories – Kruskal Wallis Test Results

Source: Computed based on data from Field Survey, 2019.

The possession of cultural capital is well reflected in the capability to nurture interests in varied fields such as language and literature, arts, music and films. Numerous statements to identify the interests, capabilities and skills demonstrated by the students in the fields of literature and arts were framed. The responses of the ST and non-ST categories of students were elicited using a 5- point rating scale ranging from 1 to 5 with lower end value 1 indicating strongly disagree and the higher end value 5 indicating strongly agree for the positive statements framed. Computation of mean scores based on the responses given by the students enables us to make a comparison between ST and non – ST students.

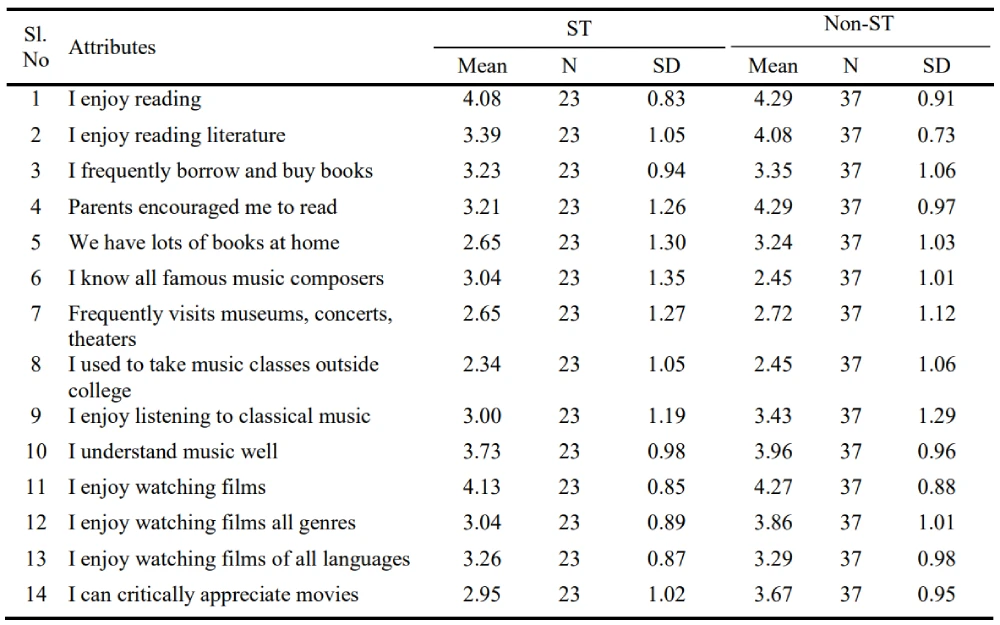

Table 4: Statements on the Students’ Interests and Capabilities in Literature, Arts and Films

Source: Computed based on data from Field Survey, 2019.

The mean scores obtained for a range of statements pertaining to the skills and interests in books and literature display that the non-tribal students have a clear edge over the tribal students. There is a disparity in the mean scores obtained for ST and non – ST students in all the statements relating to interests and skills in reading and literature with the scores of the former consistently below the latter. This is evident from the first 5 statements in Table 4.

But when it comes to their interests and capabilities in the area of arts and music and other aesthetics, it is interesting to observe the higher mean score registered by the ST students vis-à-vis the non-ST students in statement on their knowledge about music composers. However, the mean score obtained for non- ST students happen to be higher in the case of statements like training they have received in music (2.34 for ST and 2.45 for non-ST), their interests in classical music (3.00 for ST and 3.43 for non-ST) and also the frequency of visits to concerts, theaters and museums (2.65 for ST and 2.72 for non-ST). Though the ST students have innate talents and interests in music and arts, they do not have the capabilities to enhance their potential in the field as they are not exposed to training in music and they have fewer opportunities to listen to classical music and they seldom visit music concerts, theatre and museums. It is very evident that the ST students despite possessing innate aptitude and flair for music and arts are deprived of opportunities and exposures to develop and nurture cultural capital. Further cultural capital inherited by ST students is totally different from their counterpart. Despite the traditional agricultural knowledge, local and tribal treatment skills, tribal folk arts and music inherited by tribal students, they get little opportunities to showcase their talents in the present educational system. Though their parental reading behaviour is not same as non-ST group, they were able to acquire or inherit a different type of knowledge from their parents which is not available to others. Inequality in educational attainment is due to difference in the parental cultural resources.

Films are indeed a popular means of entertainment and enjoy considerable mass appeal as both ST and non-ST students have recorded high mean scores relating to the statements on enjoyment in watching films. But when it comes to enjoying films of all languages, non-ST students have a clear edge over the ST students. Further, when it comes to a serious approach to film viewing as evident from the statements such as watching films of all genres and capabilities to critically appreciate movies, the non – ST students have recorded higher mean score of 3.67 over and above 2.95, the mean score recorded by the ST students. These can be cited as proof on the possession of cultural capital by non-ST students compared to ST students. The study observed that present educational system is not suited for tribal students. To improve their educational condition, it is necessary to design special curriculum that is connected with life and needs of tribal communities.

III Policy Implications

Deficit in cultural capital encountered by the tribal students vis-à-vis the non – tribal students definitely call for enhanced policy intervention and affirmative action that strive to build up and accumulate cultural capital among the tribal students. Policy action can assume multiple dimensions such as fair implementation of reservation policy to ensure the enrolment of tribal students in the field of higher education, restructuring of the curriculum to suit the needs of tribal students enabling them to nurture and promote their innate talents and interests, provision of special coaching and mentoring to these students to prevent drop outs, etc., can be crucial in creating cultural capital base in the present generation tribal students.

IV Conclusion

Cultural capital deficit observed among tribal students not only serves as a barrier to attain better educational outcomes but also denies the posterity from enjoying the benefits of the accumulated cultural capital base of the earlier generations. Lower pass percentage in qualifying examinations, lower enrolment rates, higher drop-out rates, etc., would reduce the prospects of tribal students from acquiring cultural capital. Further, the issue of lack of cultural capital is reinforced by the absence of other forms of capital such as economic capital, financial capital and social capital which in turn has the possibility of creating a vicious circle dimming the educational prospects of the underprivileged. All these call for an affirmative action to enhance cultural capital base of the tribal students so as to offer them a level playing field to better educational outcomes.

Affiliation

Parvathy P, Associate Professor of Economics, Government Victoria College, Palakkad 678001,

Kerala, Email: parvathy.stc@gmail.com, Contact number: 9895084418

Kavitha A.C., Associate Professor of Economics, Government College, Chittur, Palakkad 678104,

Kerala, Email: ackavithagvc@gmail.com, Contact number: 6235100662

References

AISHE (2020), Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India.

Bodovski, Katerina, Jeon, Haram and Byun, Soo-yong (2017), Cultural Capital and Educational Outcomes in Post Socialist Eastern Europe, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(6):887-907.

Bourdieu, P. (1986), The Forms of Capital, In: Richardson, J., Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, Westport.

DiMaggio, P. (1982), Cultural Capital and School Success: The Impact of Status Culture Participation on the Grades of U.S. high School Students, American Sociological Review, 47(2): 189-201.

Economic Review (Various issues), Kerala State Planning Board, Govt. of Kerala.

Graaf, N.D., and P.M. de Graaf (2000), Parental Cultural Capital and Educational Attainment in Netherlands: A Refinement of the Cultural Capital Perspective, Sociology of Education, 73(2): 92-111.

Jaeger, Mads Meier and Kristian Karlson (2018), Cultural Capital and Educational Inequality: A Counterfactual Analysis, Sociological Science, 5(33): 775-795.

Lareau, Annette and Weininger, Elliot B. (2003), Cultural Capital in Educational Research: A Critical Assessment, Theory and Society, 32(5/6): 567-606.

Pavic, Zeljko and Marina Dukic (2016), Cultural Capital and Educational Outcomes in Croatia: A Contextual Approach, Sociologia, 48(6): 601-621.

Syamprasad, K.V. (2019), Merit and Caste as Cultural Capital: Justifying Affirmative Action for the Underprivileged in Kerala, India, Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 17(3): 50-81.