Middle Class and Development: A Study of Indian State

March 2024 | R. Ahalya and Sourabh Bikas Paul

Abstract

This paper explores the effect of middle class share on economic performance and institutional outcomes across Indian states. It is argued that the middle class has a role in creating better economic and institutional outcomes. A three stage least squares model is used to study the association between economic/ institutional outcomes and middle class across Indian states. The results show that middle class size has an impact on GDP per capita and its growth. Middle class share positively influences health outcomes, but does not affect some other institutional outcomes. There is no prior empirical analysis dealing with the role of middle class in shaping economic development and institutions in the Indian

context. This paper attempts to fill this gap by systematically studying the relationship using an econometric model.

Key Words

Middleclass, Economic performance, Institutions, Indian states.

This paper studies the links between middle class across Indian states and various socioeconomic outcomes. Do states with a larger proportion of middle class have better economic development and growth? Does the middle class have any role to play in creating better institutions? What are the implications of caste and religious heterogeneity on these outcomes? The rapid growth of middle class in India is seen as an important harbinger of social change. It is also arguably the most significant factor shaping the developmental outcomes (Li 2010). It has been noted that policies to encourage middle class may be important to create a society with values that can contribute to higher economic growth (Amoranto, Chun, and Deolikar 2010). In a pioneering work, Easterly (2001) finds that the regions with higher income share of middle class and lower ethnic divisions tend to have higher income as well as better developmental outcomes. He defines ‘middle class consensus’ as a high share of income for the middle classes and low degree of ethnic divisions. The paper further claims that a society with small middle class income share will have more poverty and a powerful wealthy elite class. A large middle class is associated with greater equality of opportunity and is characterized by stronger institutions (Savoia, Easaw and McKay 2010). According to Landes (1998), ideal growth and development society would have a relatively large middle class and a well-functioning democracy. Barro (1999) finds that democracy rises with the middle class share using a panel of 100 countries during the period 1960 to 1995. While these studies establish the consensus hypothesis in a macro perspective, the impact of emerging middle class on economic outcome within a country as diverse as India is very pertinent by its own merit.

The literature on middle class in the Indian context has two broad strands. The first strand deals with the empirical and qualitative study of middle class examining its composition and political role (Sridharan (2004), Fernandes (2000), Banerjee and Duflo (2008)). The other strand relates to studies on consumption behavior of the middle class and its role in driving the goods and services market (Beinhocker, Farrell, and Zainulbhai (2007), and Mathur (2010)). It is clear from the pre-existing studies that the emerging middle class in India has a lot of potential to shape the future of the country through its consumption behaviour and its influence on political outcomes. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no study looking at the link between middle class, and developmental outcomes in India, particularly at the state level. The study of middle class from a state level perspective is important in a socioeconomically diverse country like India with a large democracy. Stark disparities exist across states in terms of the socioeconomic and political environment. This paper aims to be a precedent in studying the Indian middle class at the state level, and establishing the nature of its relationship with developmental outcomes. Lobo and Shah (2015) state that a holistic study of the middle class, and its relationship to the broader issues of development, society and culture remains a less explored but a hugely interesting area. According to Jodhka and Prakash (2011), middle class has to be understood analytically in terms of its role in relation to state, market and civil society. We must study the role of middle class along with the caste and religious divisions in the state as they determine the environment in which the middle class operates (Fernandes (2000) and Sheth (1999)). In this paper, we try to fill this gap in literature by studying the relationship of middle class with economic, social, and institutional outcomes while taking into account the effect of social disparities.

There is hardly any consensus in literature on how to define and measure the size of middle class. We use the absolute consumption criteria given by Kharas (2010) to define middle class. We construct a panel comprising of all Indian states and union territories for middle class share and the outcome variables for the years 1987, 1993, 1999, 2004, 2009 and 2011 corresponding to the National Sample Survey Organization’s (NSSO) rounds. The approach of this paper differs from Easterly’s approach in the use of the share of middle class in the total population as the main explanatory variable instead of the share of income of middle class in the total income. We consider this approach as more appropriate from a developing country perspective since we use the absolute consumption expenditure cut offs to define middle class instead of the relative income approach used by Easterly.1 We regress each outcome variable on the share of middle class, caste heterogeneity, religious heterogeneity, urbanization ratio, and other controls. The results of the paper show that middle class does have a positive and significant effect on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, and economic growth. Among the institutional outcomes, middle class size has a positive influence on health outcomes.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In section I, the nature and role of middle class in India across states and over time is discussed. Section II deals with the data used in the study, and summary statistics of the variables are discussed. Section III and IV discuss the relationship of middle class with economic and institutional outcomes respectively, the methodology used, and the results obtained. Section V analyses the problem of endogeneity in the model. In section VI, the results are discussed and the chapter is concluded.

I The Role of Middle Class in the Indian Context

Since the inception of middle class in India during the British rule, it has been a modernizing social category and an important agent of social change in Indian society (Jodhka and Prakash 2016). The role of middle class in society is looked at in light of its relationship with working class and the politically powerful bourgeoisie class. Although conventional Marxist theory was sceptical about the survival of middle class as an independent entity, neo Marxians have realized that middle class has not only survived and expanded but has been successful at weakening the exploitative relationship between the actors in a dichotomous society comprising of the bourgeoisie and the proletariats. It has been established across societies, that middle class have attributes that support democratic principles and engage in actions for the rise and maintenance of a democratic system (Eulau 1956, Lipset and Raab 1981). It has been determined that a society with a large middle class tends to be less unequal in terms of distribution of socioeconomic resources (Muller 1988). The effect of economic growth and development on the establishment of a democratic polity is not direct but works through the effect of middle class in the society (Lipset and Raab 1981, Rueschemeyer, Stephens, Stephens, et. al. 1992).

Despite the rich sociological literature on the subject, very few attempts have been made to identify the composition of middle class and the impact it has on the economy. According to Brandi and Bu¨ge (2014), there are a variety of different middle classes in developing countries whose growth, size and consumption capacities vary. In order to take the heterogeneous nature of the emerging middle class into account, they create a typology of middle class comprising nine different types of middle classes, ranging from a small and affluent middle class to a poor large middle class. This kind of typology enables us to study the diverse nature of middle class across regions. Sridharan (2004), in his essay analyses the growth of middle class in India since 1980, focusing on the liberalization of 1991. The variations in the nature of relationship between economic growth, and middle class are due to differences in the social and cultural makeup of the region (Amoranto, Chun, and Deolikar 2010). The paper studies how the emergence of this class and its composition has affected the liberalization process in India. According to the paper, the class structure has changed from one with a small wealthy elite class and the poor masses, to one where an intermediate class of middles has been created. According to the paper, a society where the middle class have little say in shaping government policies, the rich will strive to fulfil their vested interests by promoting skewed socioeconomic policies that are at divergence with the interests of masses.

The main hypothesis of the chapter is based on the middle class consensus theory proposed by Easterly (2001). In this paper, easterly studied the effect of middle class income share on GDP per capita and its growth rate for 175 countries using tropical endowment (primary commodity exports) in a country, as an instrumental variable for middle class. Ethnic fragmentation in a country was used as a control variable in the regression. The results of the paper showed that the presence of a stronger middle class and lower ethnic fragmentation in a region leads to better economic outcomes. We revisit this hypothesis in the context of Indian states since every state of India is unique in its socio economic and cultural characteristics. The second part of the Easterly’s hypothesis focuses on the effect of ethnic fragmentation on public outcomes due to divergent interests among multiple groups. According to Alesina, Baqir, and Easterly (1999), social fragmentation is associated with reduced access to local public goods, often because it inhibits communities from working collectively to extract public goods from the state. In the Indian context, Banerjee, Iyer, and Somanathan (2007) find that greater caste and religious divisions negatively affect access to public goods. Although the main focus of the present study is to establish the relationship between middle class and various public outcomes, it is necessary that we control for caste and religious heterogeneity across states.

This paper attempts to study the role of middle class in shaping better institutions across Indian states. It has been well established that the quality of economic and democratic institutions determine growth and development in a society (Acemoglu and Robinson (2005), Easterly, Ritzen, and Woolcock (2006)). It has also been shown that the middle class play a crucial role in shaping better institutions (Loayza, Rigolini, and Llorente 2012, Savoia, Easaw, and McKay 2010). Therefore, it is hypothesized that higher share of middle class in a region creates better institutions which in turn lead to better socioeconomic outcomes. Although we acknowledge that the mechanisms which govern these relationships are complicated and can be investigated using various sociological, anthropological, and economic tools, we study the relationship using a relatively simple empirical specification. This may not capture all possible interactions of middle class with the economy and society, but gives us insights on the direction in which middle class affects economic and institutional outcomes at the state level in India.

II Research Methodology

We can use a simple OLS and a state fixed effects model to study the effect of middle class share on various outcome variables. However, this specification may suffer from possible endogeneity issues due to omitted variables or simultaneity. In such circumstances, it is difficult to determine whether the causality is bidirectional or unidirectional. It is important to disentangle this confoundedness of causality in order to understand the relationship between the variables. We propose to correct for this problem of endogeneity by using a suitable instrumental variable for middle class share. The state wise share of non-agricultural employment in the total employment is used as an instrument for middle class share. It has been well documented in literature that India’s economic development has been led by a shift from agriculture to non-agricultural employment, specifically service sector employment. For instance, Gordon and Gupta (2003) find that India’s growth experience has been characterized by a decline in the share of agriculture in GDP and an increase in the share of industry and services. Jodhka (2012) finds that the industry and service sector continue to absorb more and more people and the middle class are predominantly located in the service sector. Sridharan (2004) highlights the importance of middle class as economies shift away from agriculture and towards the service sector. Fernandes (2000) has also found that the middle class in India is characterized by the new economy service sector. It has been noted that the expansion of middle class in developing Asia has been driven by the rapid structural transition from agriculture, to industry and services (Huynh and Kapsos 2013). Clearly, the middle class is mostly employed in non-agricultural occupations rather than agriculture, and thus it will be appropriate to use employment in non-agricultural sectors as an instrumental variable for middle class size.

However, it is also apparent that non-agricultural employment share is itself endogenous in the model since it is likely to be associated with the outcome variables. In order to rectify this, we use historical average variation in rainfall across states as an instrument for non-agricultural employment share. Skoufias, Bandyopadhyay, and Olivieri (2017) study the effect of historical rainfall variability on the shift of household employment away from agriculture to non- agricultural sectors. The analysis revealed that high rainfall variability has a significant negative effect on the agricultural focus of within-household occupational choices. We use this finding as the justification of the choice of the instrumental variable.

In this manner, we run a three stage least squared regression model for the purpose of our study. This is more efficient as compared to the two stage least squares because the problem of serial correlation may still persist due to simultaneity. In the first stage, the share of non-agricultural employment is regressed on the coefficient of variation of rainfall averaged over the period 1950 to 2002 across Indian states. Since the historical coefficient of variation in rainfall is time invariant, we use the Fixed Effects Filter (FEF) model (Pesaran and Zhou 2018). This is done in order to correct the bias occurring due to the correlation of these variables with the individual effects. In the first step, use a state fixed effects model to regress the share of non-agricultural employment on the time varying factors as follows:

𝑦it = α + 𝛽𝑧it + sit

In the second step of the FEF regression, the mean of the residuals from the above equation is regressed on the time invariant factor as follows:

𝑦it = α + 𝛽𝑥i + sit …(1)

Where, yit is the share of non-agricultural employment, xi is the time invariant variable (the coefficient of variation of rainfall), and Ɛit is the error term, for the ithstate and tth time period. The coefficient of variation of rainfall is calculated as the ratio of the variance and mean of the average historical rainfall over the years 1901 to 2002, for each state.

In the second stage, we regress the predicted values of non-agricultural employment on the middle class share using a pooled OLS specification as shown below:

𝑦it = αit + 𝛽1𝑥it + 𝛽𝑧it + sit …(2)

Where, yit is the middle class share, xit is the predicted non-agricultural employment, zit is a vector comprising of a set of control variables, and Ɛit is the error term.

In the third stage, the outcome variables are regressed on the predicted middle class share, using generalized least squares method as shown below:

𝑦it = αit + 𝛽1𝑥it + 𝛽𝑧it + sit …(3)

Where, yit is the outcome variable, xit is the predicted middle class share, zit is a vector comprising of a set of control variables, and Ɛit is the error term.

III Data and Summary Statistics

Measuring Middle Class

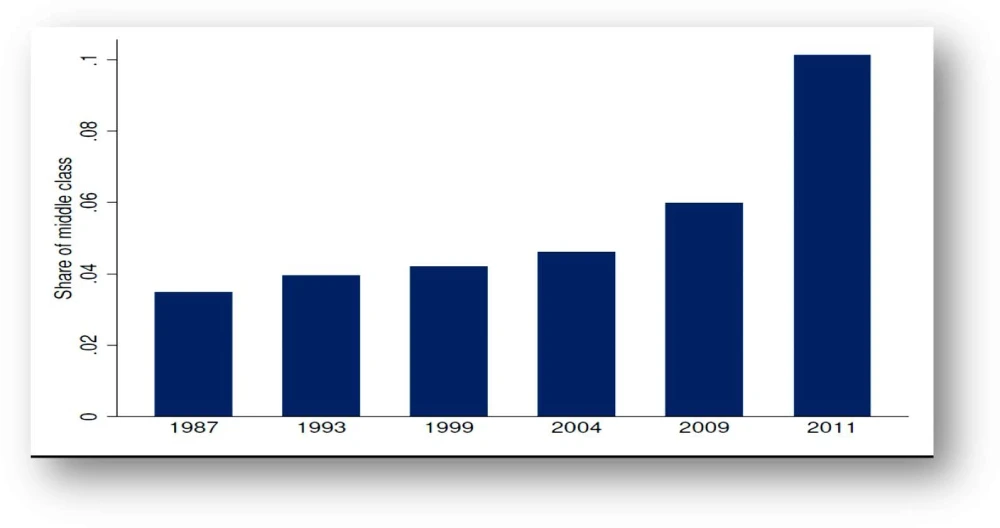

All thick rounds of the NSSO consumption expenditure data for the time period 1987-2011 are used for creating a state wise panel of share of middle class households in Indian states and union territories. We follow Kharas (2010) to define the middle class based on consumption expenditure criteria. Households with per capita per day consumption expenditure between $10 and $100 at Purchasing Power Parity are considered to be middle class.2 We use the average Consumer Price Index (CPI) index for agricultural labourers (rural) and industrial workers (urban) for the period 1987-2011, to obtain the inflation adjusted cut offs for different years. Before turning to the more concrete findings of the paper, we look at how the size of middle class has changed over the period 1987-2011. The bar graph in figure 1 shows that overall percentage of global middle class in India has consistently increased from around 3.5 per cent in 1987 to about 7.5 per cent in 2011.

Figure 1: Share of Middle Class during 1987-2011

Source: Authors’ calculation using NSSO consumption expenditure data for the years mentioned

The shares are calculated in the total households in the sample for each year.

Measuring Other Variables

We use the proportion of middle class in Indian states as the main explanatory variable in the study. The other explanatory variables used in this paper are caste and religious heterogeneity. The index is based on the Herfindahl Hirschman index and is given as one minus the sum of the squares of the proportion of all caste (or religious) groups in each state. The caste, and religious heterogeneity index is given by the following formulas:

RHI = 1 − (Σ(Religioni)2)

CHI = 1 − (Σ(Castei)2)

where RHI and CHI refer to the religious and caste heterogeneity indices respectively while Religioni and Castei refer to the proportion of the ith religion and caste in a particular state. Another control variable used in the study is urbanization ratio which is defined as the ratio of urban households to the total households in a state, and is obtained from the NSSO consumption expenditure data.

We divide the dependent variables into two categories: economic outcomes and institutional outcomes. The major variable in the study is GDP per capita and its growth rate. We obtain nominal state GDP data from the Central Statistical Organization (CSO) website and it is inflation adjusted using CPI index. The GDP per capita is calculated by dividing it by the state wise population.3 The GDP per capita growth rates for each year is calculated as the average of the GDP per capita growth rates during the previous two years and the next two years. We obtain the data on school enrolment rates and other control variables from the Census of India, and GOI Annual reports. The source of data on Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) and life expectancy are National Family Health Survey (NFHS) reports, and the handbook of statistics published by the reserve bank of India.

We measure the quality of institutions in terms of administrative efficiency, democratic participation and financial inclusiveness. Administrative efficiency is proxied by the extent of power loss during transmission and distribution due to misuse and corruption. According to Subramanian (2007), it reflects the quality of state level politics as well as state level bureaucracy (the state electricity boards) which enforce the laws. The annual reports of state electricity boards provide data on Transmission and Distribution (TD) losses of power. Democratic participation is measured by the share of adults who participate in the voting process in a state. We get data on voter turnout rates in the general elections from the election commission of India reports for the nearest year, in which the general elections were held.

Inclusive financial institutions are crucial for socio economic development and inclusive growth. The strength of financial institutions can be determined by their outreach and extent of utilization. In 1969, the banks were nationalized to strengthen the banking system and spread it across all sections of the society. We can define financial inclusion as a process that ensures the ease of access, availability and usage of the formal financial system for all members of an economy (Sarma 2008). According to Dixit and Ghosh (2013), inclusive growth strategy should not only aim at equitable distribution of growth benefits, but creating economic opportunities and equal access to them for all. Access to formal savings and credit mechanisms facilitate investment in productive activities such as education or entrepreneurship. Lacking such access, individuals rely on their own limited, informal savings to invest in education or business, and small enterprises on their limited earnings. This can contribute to persistent income inequality and slower economic growth (Demirguc-Kunt and Klapper 2013). We construct a multidimensional financial inclusiveness index using the method suggested by Sarma (2008). The index is constructed using three basic parameters: banking penetration, availability of banking services and usage of the banking system. We obtain data on banking penetration, availability and usage from various reports of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

The share of non-agricultural employment is obtained from the NSSO Employment and Unemployment Surveys, and the data on historical rainfall is obtained from the Indian Meteorological Department’s website. These are used as instrumental variables in our regression analysis.

IV Economic Outcomes and Middle Class

As already discussed, a large middle class is correlated with better economic performance. In order to determine whether middle class share affects economic outcomes, we have to choose a suitable empirical model.

Firstly, we use a simple pooled OLS specification to see the effect of middle class on economic performance. Then we use a state fixed effects model to study the same, Finally, we use the three stage least squares model to counter the problem of endogeneity, as discussed earlier. The other control variables used in the regression are caste and religious heterogeneity indices, urbanization ratio, school enrolment rates, credit deposit ratio, social sector expenditure as a share of GDP, population growth, and FDI expenditure per capita. Further, we control for the initial GDP per capita and its square as per the specification for GDP and growth regressions suggested by Barro (1991). The period dummy is included as a control for aggregate time effects.

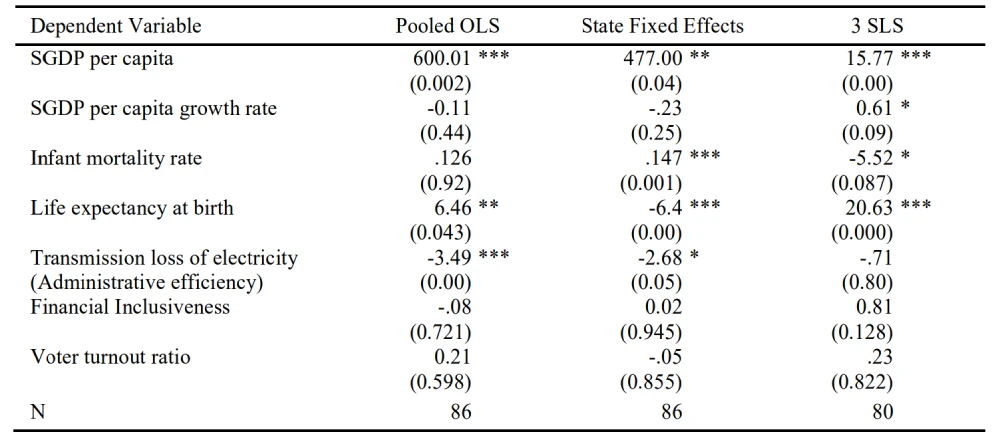

Table 1: Impact of Middle Class on Various Socio-Economic Outcomes

Explanatory/independent variable: Middle class share in population

Notes: t-statistics in parentheses; ∗p<0.1, ∗∗p<0.05, ∗∗∗p<0.01. Standard errors reported are robust.

Period dummies are included in all specifications.

Caste heterogeneity, religious heterogeneity, urbanization ratio, household size, initial GDP per capita, school enrolment ratio, share of social sector expenditure in GDP, share of agriculture in GDP, literacy rate, square of initial GDP per capita, and per capita FDI investment in the state are included as additional control variables.

Source: Author’s calculations using NSSO consumption expenditure data.

The results of the regression of GDP per capita and GDP per capita growth rate on middle class share is shown in Table 1. Middle class share has a positive and significant effect on GDP per capita as well as on GDP per capita growth, when the three stage least squares is used. Religious heterogeneity does not have any effect on GDP per capita or its growth rate. Caste heterogeneity has a negative and significant effect on GDP per capita growth, when the state fixed effects model is used. This may indicate lower economic growth due to caste based discrimination in states with more caste diversity. Greater urbanization ratio in a state is also associated with lower GDP per capita when a 3SLS model is used. The middle class has been recognized as a facilitator of consumption and investment since John Maynard Keynes published his book The General theory of employment, interest and money (Keynes 1936). Since liberalization in India, the new emerging middle class has been projected as an important agent for economic development. It is clear from the present analysis that states having a larger middle class have higher GDP per capita. The effect of middle class on economic growth may occur with a lag, since poorer states tend to grow faster than richer states. So, our results are in accordance with the hypothesis that states with a larger middle class have better economic performance.

V Institutional Outcomes and Middle Class

In this section, we analyse the relationship between the quality of institutions in Indian states and middle class share. The institutional outcomes considered here are health outcomes (IMR and life expectancy), administrative efficiency (measured by transmission and distribution loss of electricity as a proportion of availability), inclusiveness of financial institutions and democratic participation (measured in terms of voter turnout ratio). While the poor and the rich are indifferent about corrupt and undemocratic institutions, the middle class benefit from better quality institutions (Easterly 2001). It has been well established that middle class campaign for creation of better institutions and are crucial for a well- functioning democracy (Loayza, et. al. 2012, Savoia, et. al. 2010). We now study the relationship using an empirical specification.

We study the relationship using different specifications controlling, for the period dummy as has already been discussed. The results of the regression are shown in Table 1. When the three stage least squares model is used, IMR negatively affects middle class share and positively affects life expectancy, indicating its positive influence on health outcomes. However, middle class share has a negative and significant effect on transmission, and distribution loss of electricity. Also, its effect on financial inclusiveness and voter turnout ratio is not significant in any of the specifications. The results indicate that middle class has a role in creating better administrative institutions. However, there are limitations of this study since data on corruption and administrative quality is not available, but it has been proxied by transmission and distribution losses of power, that indicates the efficiency of electricity transmission. Since well-functioning institutions catalyse economic and social development, the positive influence of middle class on economic development shows that institutions may act as channels for economic development. Middle class does not affect financial inclusiveness, since more inclusive financial institutions have been established in poorer states. The positive relationship between middle class and democratic participation is only due to co-variation over time and the empirical evidence supports no such relationship.

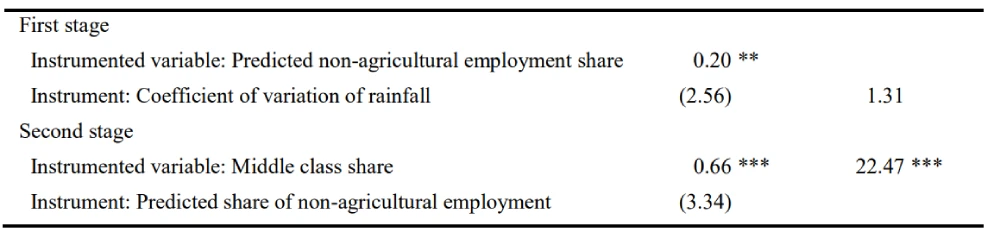

VI Validity of the Instrumental Variables

We have already discussed the appropriateness of the instruments used in this study, based on their fulfilment of the conditions of exogeneity, and their correlation with the instrumented variables (Woolridge 2012). This we had done based on previous literature that has highlighted these relationships. Further, we also validate the use of these instruments using statistical evidence. We show that the coefficients of the instrumental variable in the first stage, and the second stage regressions of the 3SLS model are significant, indicating their partial correlation with the instrumented variables, in this case, non-agricultural employment share, and middle class share respectively (the F-statistics may not be a reliable indicator for panel fixed effects regression). These results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Validity of the Instrumental Variables

Notes: t-statistics in parentheses; *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01. Standard errors reported are robust.

Period dummies are included in all specifications.

Source: Author’s calculations using NSSO consumption expenditure data.

VII Conclusion

The basic hypothesis explored in this chapter, is that states with a larger middle class and lower social heterogeneity will have better economic and institutional outcomes. This is based on the assumption that when power is in the hands of a small affluent dominant group, it will try to appropriate the resources for their own benefit rather than pushing for better economic and social outcomes. The Wald statistics are found to be significant for all the outcome variables in our study, except for financial inclusiveness, indicating that the three stage least squares model is appropriate to counter the problem of endogeneity. The study shows that a larger middle class share in the population creates better economic, and health outcomes, although its effect on the other institutional outcomes is questionable. Caste and religious heterogeneity do not have a significant effect on economic outcomes. However, religious heterogeneity has a positive influence on health outcomes, while caste heterogeneity has a negative influence on them.

The results of this chapter indicate that in order to achieve higher GDP targets and effective institutions, the government must encourage the growth of middle class households by promoting higher education, and creating more job opportunities. In the Indian scenario, there are enormous prospects for economic mobility among the masses who are aspiring to be a part of the new middle class, provided people are given equal opportunities for skill acquisition and employment. Since the impact of middle class is important at the state level, policies to encourage economic mobility must operate at the federal level. A large and economically mobile middle class must be encouraged not just for better economic performance, and effective administration, but for a more equitable and just society. This study confirms and reinforces the view that a middle class society is instrumental in creating an environment of economic progress. Further, it highlights the importance of middle class at the state level, in a heterogeneous economy like India. Therefore, this study is the first attempt at empirically justifying the importance of middle class for socio economic development in India.

Endnotes

We have tested our hypothesis using both the middle class share in population and the consumption share of middle class in total consumption. We find that the results using both are very similar in terms of its significance level and the sign of the coefficients in all the regressions used in this chapter. Only the size of the coefficients differ somewhat between the two methods

Compared to other measures such as Banerjee and Duflo (2008) and Meyer and Birdsall (2012), the Kharas (2010) measure has been found to be more appropriate for the present analysis. While the Banerjee and Duflo (2008) criterion has lower cut off for middle class below the poverty line, Meyer and Birdsall (2012) measure is income based. The relative approach (Easterly, 2001) is also not appropriate, since the measure includes poor households in middle class bracket. Our measure gives the state wise benchmark identifying households that can afford to live comfortably without facing too much risk of falling in poverty.

In our analysis, real State GDP is expressed in ₹100 units at the base of 1987.

Affiliation

R. Ahalya, Daulat Ram College, University of Delhi, Delhi 110007, Email: rahalya@dr.du.ac.in

Sourabh Bikas Paul, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology,

Delhi 110016, Email: sbpaul@iitd.ac.in

References

Acemoglu, D. and J.A. Robinson (2005), Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy, Cambridge University Press.

Alesina, A., R. Baqir and W. Easterly (1999), Public Goods and Ethnic Divisions, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(4): 1243–1284.

Banerjee, A. and E. Duflo (2008), What is Middle Class About the Middle Classes Around the World? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2): 3–41A.

Banerjee, A., L. Iyer and R. Somanathan (2007), Public Action for Public Goods, Handbook of Development Economics, 4: 3117–3154.

Barro, R.J. (1991), Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2): 407-443.

———–(1999), Determinants of Democracy, Journal of Political Economy, 107(S6): S158–S183.

Beinhocker, E.D., D. Farrell and A.S. Zainulbhai (2007), Tracking the Growth of India’s Middle Class, McKinsey Quarterly, 3: 51-61.

Brandi, C. and M. Bu¨ge (2014), A Cartography of the New Middle Classes in Developing and Emerging Countries, Deutsches Institutfu¨r Entwicklungspolitik.

Cole, G.D.H. (1950), The Conception of the Middle Classes, The British Journal of Sociology, 1(4),275–290.

Demirgűc-Kunt, A. and L. Klapper (2013), Measuring Financial Inclusion: Explaining Variation in Use of Financial Services across and within Countries, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2013(1): 279–340.

Dixit, R. and M. Ghosh (2013), Financial Inclusion for Inclusive Growth of India: A Study of Indian States, International Journal of Business Management and Research (IJBMR), 3(1): 147–156.

Easterly, W. (2001), The Middle Class Consensus and Economic Development, Journal of Economic Growth, 6(4): 317–335.

Easterly, W., J. Ritzen and M. Woolcock (2006), Social Cohesion, Institutions, and Growth, Economics and Politics, 18(2): 103–120.

Eulau, H. (1956), Identification with Class and Political Role Behaviour, Public Opinion Quarterly, 20(3): 515–529.

Fernandes, L. (2000), Restructuring the New Middle Class in Liberalizing India, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 20(1): 88–104.

Gupta, M.P. and M.J.P. Gordon (2003), Portfolio Flows into India: Do Domestic Fundamentals Matter? (No. 3-20), International Monetary Fund.

Gupta, P., S. Mallick and T. Mishra (2018), Does Social Identity Matter in Individual Alienation? Household Level Evidence in Post-Reform India, World Development, 104: 154–172.

Jodhka, S.S. and A. Prakash (2011), Indian Middle Class: Emerging Cultures of Politics and Economics, KAS International Reports, 12: 42-56.

———-(2016), The Indian Middle Class, Oxford University Press.

Keynes, J.M. (1936), The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Harcourt, Braceand Co., New York.

Kharas, H. (2010), The Emerging Middle Class in Developing Countries, working paper, OECD Development Centre, 285, page 1-61.

Landes, D.S. (1998), The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Are Some So Rich and Others So Poor, NewYork: WWNorton.

Li, C. (2010), China’s Emerging Middle Class: Beyond Economic Transformation, Brookings Institution Press.

Lipset, S.M. and E. Raab (1981), The Election and the Evangelicals, Commentary, 71(3): 25.

Loayza, N., J. Rigolini and G. Llorente (2012), Do Middle Classes Bring About Institutional Reforms? Economics Letters, 116(3): 440–444.

Lobo, L. and J. Shah (2015), The Trajectory of India’s Middle Class: Economy, Ethics and Etiquette, Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Mathur, N. (2010), Shopping Malls, Credit Cards and Global Brands: Consumer Culture and Lifestyle of India’s New Middle Class, South Asia Research, 30(3): 211–231.

Meyer, C. and N. Birdsall (2012), New Estimates of India’s Middle Class, CGD Note, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC.

Muller, E.N. (1988), Democracy, Economic Development, and Income Inequality, American Sociological Review, 53(1): 50–68.

Pesaran, M.H. and Q. Zhou (2018), Estimation of Time-Invariant Effects in Static Panel Data Models, Econometric Reviews, 37(10): 1137-1171.

Power, S., T. Edwards and V. Wigfall (2003), Education and the Middle Class, McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Rueschemeyer, D., E.H. Stephens, J.D. Stephens, et. al. (1992), Capitalist Development and Democracy, Vol. 22, Cambridge Polity.

Sarma, M. (2008), Index of Financial Inclusion (Tech. Rep.), Working Paper number 215, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations.

Savoia, A., J. Easaw and A. McKay (2010), Inequality, Democracy, and Institutions: A Critical Review of Recent Research, World Development, 38(2): 142–154.

Sheth, D. (1999), Secularisation of Caste and Making of New Middle Class, Economic and Political Weekly, 34: 502–2510.

Skoufias, E., S. Bandyopadhyay and S. Olivieri (2017), Occupational Diversification as an Adaptation to Rainfall Variability in Rural India, Agricultural Economics, 48(1): 77-89.

Sridharan, E. (2004), The Growth and Sectoral Composition of India’s Middle Class: Its Impact on the Politics of Economic Liberalization, India Review, 3(4): 405–428.

Subramanian, A. (2007), The Evolution of Institutions in India and Its Relationship with Economic Growth, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 23(2): 196–220.